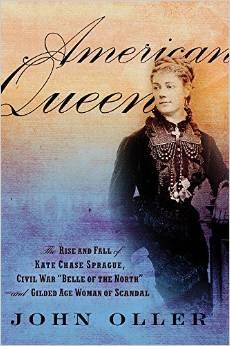

American Queen: The Rise and Fall of Kate Chase Sprague, Civil War “Belle of the North” and Gilded Age Woman of Scandal by John Oller. DaCapo Press, 2014. Cloth, IBSN: 978-0306822803. $25.99.

John Oller has delivered a book full of engaging detail and captivating characters to illuminate the career of Kate Chase Sprague, who began her meteoric rise as a favorite topic of society gossip when her father Salmon Chase failed in his bid as Republican presidential nominee in 1860, then went on to become Lincoln’s Secretary of Treasury in 1861 and Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in 1864. Yet this vivid portrait of a vivacious and complex woman who defied the dictates of her day is no mere biography.

John Oller has delivered a book full of engaging detail and captivating characters to illuminate the career of Kate Chase Sprague, who began her meteoric rise as a favorite topic of society gossip when her father Salmon Chase failed in his bid as Republican presidential nominee in 1860, then went on to become Lincoln’s Secretary of Treasury in 1861 and Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in 1864. Yet this vivid portrait of a vivacious and complex woman who defied the dictates of her day is no mere biography.

Oller weaves in fascinating details of rivalries and alliances launched in Civil War Washington which influenced political agendas during Reconstruction and what followed, the so-called Gilded Age, which appears considerably tarnished via Oller’s lens. Oller uses young Kate Chase’s engagement with politics and great men to interpret twists and turns during this volatile era. But he also powerfully invokes the way in which the press reflected and stimulated political intrigue and downfall. Indeed, even before Kate Chase arrived in Washington, she was the focus of scandal—presumably because of her feud with the incoming First Lady, Mary Lincoln, whose husband had dashed Chase’s hopes for White House residency. But this tempest was not a solo squall, as Kate’s lifeblood was fueled by political intrigue, a claim Oller substantiates vividly through the use of correspondence, diary entries, and, most pointedly, the penny press of her day. The “personal” was political is emphatically demonstrated by tracing varied linkages, alliances, and rivalries that stoked her grand ambitions. Her invitational breakfasts at Secretary Chase’s home at Sixth Street and E were meant to further not only her father’s prospects, but to solidify her reputation as a mover and shaker within the hothouse atmosphere of the nation’s besieged capital.

She flirted indiscriminately and was courted by an impressive coterie: John Hay, Lincoln’s private secretary who tempted her with White House tidbits, and James Garfield, her father’s protégé, who squired her around to reignite the cooled passions of a previous suitor, the infamous William Sprague. This millionaire playboy was a Rhode Island rogue when he clamped eyes on Kate. But he was able to put a ring on her finger. As one of the richest men in America, heir to a textile fortune, and the youngest man elected at twenty-nine to lead a state (nicknamed “the boy governor of Rhode Island”), Sprague cut a dashing figure at war’s outset—even before his horse was shot out from under him at Bull Run and he became a war hero. No surprise that revelations about the couple’s Washington wedding trilled across the telegraph wires, displacing war news. Kate Chase Sprague may have been the first respectable female whose exploits were so lavishly splashed across the headlines, signifying nineteenth century tabloid frenzy.

Kate explained her initial attraction to Sprague: “My fate.” The groom knew Kate was unusual (“she is very tenacious of everything”) but was smitten with the idea of their coupledom, succumbing to media romance.

Oller’s narrative uses this disastrous marriage—and Kate’s declining status—as a through line for the book. The couple went on to have four children, notorious extramarital liaisons, and divorced acrimoniously in 1882. Kate initiated the split with revelations of Sprague’s infidelities, airing the dirty linen of his longtime mistress Mary Viall and the paramours’ arrest in 1878 at a Massachusetts seaside resort following late night drunk and disorderly behavior. Kate had been aware of her husband’s infidelities when he began sleeping with the nanny in 1866. But with the death of her father in 1873 and escalating marital alienation, Kate turned her hero worship to another charismatic politician of the day, Roscoe Conkling.

Kate’s dalliance with this New York stalwart was a poor gamble. Whatever happiness the couple eked out, he would eventually return to his wife, and Kate would be branded notorious. Although they were so bold as to meet up clandestinely in Europe after travelling on separate ships, by January 1878 they appeared in public together without their spouses—ironically, this first public appearance together was at the unveiling of Francis Carpenter’s painting of Lincoln’s reading of the Emancipation Proclamation, a depiction which prominently featured Kate’s father.

There are moments in this snap, crackle and popping narrative when Oller might have slowed down and framed some of his analysis in light of compelling historical literature. There is little or no understanding of the role of abolitionism to the Chase project within this framing of Kate’s life. Did emancipation have any ideological import to her, considering its prominence in her father’s public role, and Conkling’s party commitment? Kate’s relationship to the women’s rights movement could have used some slight attention, but generally Oller is too busy tracking this beleaguered heroine. He correctly emphasizes her being handicapped by the fact that she is not Sprague’s equal, but his superior, yet gets no respect, remaining a dependent, in the shadows, and clearly disadvantaged.

As she glides back and forth across the seas, braving storms and rejections as the disreputable divorcee—Kate Chase (as she pointedly resumed her birth name) tried to hang on to her wits, her father’s estate, and her remaining family. The story unfolds in a melodramatic, spiraling fashion during the book’s second half: the crash of ’69, the divorce of ’82, the suicide of her only son William (’90). She becomes impoverished and a social outcast, excluded from those circles where she once ruled. Her death in 1899 seems to come as an afterthought to her exile from life.

Despite Oller’s bravado about Kate Chase’s independence, she was also a woman who quite literally hitched her star to the man most likely to propel her toward comfort and power. At the same time, she wholly rejected a conventional and feminine role for herself. This singular woman became a force with which even the great men of the day believed was worth reckoning.

Catherine Clinton is Denman Endowed Professor of American History at the University of Texas San Antonio and the author of many books, including Mrs. Lincoln (2009).