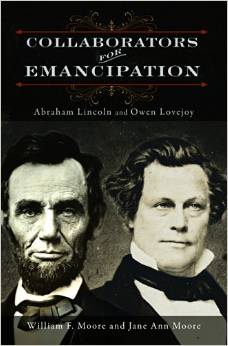

Collaborators for Emancipation: Abraham Lincoln and Owen Lovejoy by William F. Moore and Jane Ann Moore. University of Illinois Press, 2014. Cloth, IBSN: 978-0252038464. $38.00.

For a man with melancholic tendencies, Abraham Lincoln claimed many friends. Considering just those men from Illinois who served in Congress, he was close to Isaac Arnold, Orville Browning, Elihu Washburne, and Edward Baker (Lincoln named his second son, who died in 1850, after Baker). Add to the list Owen Lovejoy, who Lincoln described as “my most generous friend” after Lovejoy’s death in 1864. In Collaborators for Emancipation, William F. and Jane Ann Moore examine the relationship between the two men.

For a man with melancholic tendencies, Abraham Lincoln claimed many friends. Considering just those men from Illinois who served in Congress, he was close to Isaac Arnold, Orville Browning, Elihu Washburne, and Edward Baker (Lincoln named his second son, who died in 1850, after Baker). Add to the list Owen Lovejoy, who Lincoln described as “my most generous friend” after Lovejoy’s death in 1864. In Collaborators for Emancipation, William F. and Jane Ann Moore examine the relationship between the two men.

Lovejoy was a Congregational minister and abolitionist who served in the Illinois State legislature and was elected to Congress in 1856. He was the younger brother of Elijah P. Lovejoy, editor of the abolitionist Alton Observer, who was murdered by a pro-slavery mob in 1837. The death of Lovejoy galvanized the antislavery movement and drew widespread attention; Lincoln alluded to it in his Lyceum Address of 1838 when he denounced mob law.

Lincoln and Owen Lovejoy first met in 1854 at the Springfield State Fair. Lincoln was still attached to the Whigs, whereas Lovejoy was among the leaders in organizing a statewide Republican Party. Both were elected to the Illinois House of Representatives that year, but Lincoln resigned the seat in order to be eligible for the U.S. Senate. The Moores take a year-by year approach and trace the speeches of both men, speculating about their ideological development. Lovejoy is portrayed as consistently radical and increasingly pragmatic; Lincoln is viewed as always pragmatic but moving toward Lovejoy’s position on slavery.

Unfortunately, there is little evidence of cause and effect in the developing attitudes of both men. Indeed, in the campaign of 1856, the two appeared on the same stage only six times, and Lincoln displayed a “lingering reluctance to appear in public with Lovejoy” (46). The Moores are unable to go far beyond the statement that Lincoln’s House Divided speech “might also have been inspired” by a speech (“Human Beings Not Property”) that Lovejoy delivered in the House in February 1858. Whatever the sources of Lincoln’s speech, Lovejoy responded, “it sounds like God’s truth from the mouth of the prophet” (69).

When Lincoln debated Stephen Douglas in Ottawa, Lovejoy’s home district, Lovejoy sat on stage. Part of Douglas’ strategy was to link Lincoln to the abolitionist Lovejoy, but, in a display of deft political maneuvering, Lincoln refuted Douglas’ charge without alienating the support of radical Republicans.

The Moores argue that during the war Lincoln became more radical, and that he and Lovejoy were “collaborators for emancipation.” But Lincoln did not so much radicalize as evolve. Few radicals unequivocally sided with Lincoln who, early in the war, would not act against slavery, still favored gradual emancipation, and did not envision black suffrage as part of reconstruction. Lovejoy’s importance is not that he radicalized Lincoln, but that he continued to defend Lincoln and support his policies, no matter how deliberate or moderate. He had confidence that Lincoln would act against slavery, and he sided with the president (against the likes of Thaddeus Stevens) on the theoretical question of whether the states in secession remained in the Union.

Despite the narrow focus of this volume, it is valuable to have another study of Lincoln and one of his friends. The book fits well with such works as Maurice G. Baxter’s Orville H. Browning: Lincoln’s Friend and Critic (1957), David Donald’s We Are Lincoln Men: Abraham Lincoln and His Friends (2004), and Robert Eckley’s Lincoln’s Forgotten Friend: Leonard Swett (2012). Lovejoy’s career in Congress is the subject of Edward Magdol’s Owen Lovejoy: Abolitionist in Congress (1967), and that title is worth consulting to learn more about Lovejoy’s labors aside from his connection to Lincoln.

Louis P. Masur, Distinguished Professor of American Studies and History at Rutgers University, is the author of Lincoln’s Last Speech: Wartime Reconstruction and the Crisis of Reunion (forthcoming, 2015), Lincoln’s Hundred Days: The Emancipation Proclamation and the War for the Union (2012) and The Civil War: A Concise History (2011).