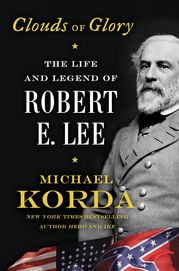

Clouds of Glory: The Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee by Michael Korda. HarperCollins, 2014. Cloth, ISBN: 0062116290. $40.00.

There are two difficulties in the path of any biography of Robert E. Lee. One is that there is no central location of Lee papers. They are scattered across libraries and archives as remote from each other as the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, and the Special Collections of Washington & Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. The other is Douglas Southall Freeman’s four-volume R.E. Lee (1934-35), which not only set the bar for Lee biography dauntingly high, but enshrined an already up-on-the-pedestal image of Lee as the chivalrous knight of the Lost Cause, sans peur et sans reproche. Thomas Connelly rocked that pedestal in 1977 with The Marble Man: Robert E. Lee and His Image in American Society, but did not overthrow it. Nor did Alan T. Nolan with Lee Considered (1991). They could challenge Freeman’s admiring conclusions, but Freeman’s sheer bulk overwhelmed and outlasted them.

There are two difficulties in the path of any biography of Robert E. Lee. One is that there is no central location of Lee papers. They are scattered across libraries and archives as remote from each other as the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, and the Special Collections of Washington & Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. The other is Douglas Southall Freeman’s four-volume R.E. Lee (1934-35), which not only set the bar for Lee biography dauntingly high, but enshrined an already up-on-the-pedestal image of Lee as the chivalrous knight of the Lost Cause, sans peur et sans reproche. Thomas Connelly rocked that pedestal in 1977 with The Marble Man: Robert E. Lee and His Image in American Society, but did not overthrow it. Nor did Alan T. Nolan with Lee Considered (1991). They could challenge Freeman’s admiring conclusions, but Freeman’s sheer bulk overwhelmed and outlasted them.

Michael Korda’s new Lee biography, Clouds of Glory, thus has a sobering task ahead of it—a task that, in almost every important respect except length, it fails. This is not because of any lack of empathy or insight on Korda’s part. He is fully alive to Lee’s “complex character,” to the peculiar mix of to-the-manor-born gentility and unforgiving self-pity, to the restless aggressiveness and the polite aversion to confrontation, to the religion which was at once pious, evangelical, and vacuous. And Korda lacks no gift for vivid story-telling. In fact, the preface, which introduces us to Lee not as the great general but as the lieutenant-colonel hastily dispatched to Harpers Ferry to capture John Brown, is worth the price of the book alone.

But there is a sense of belabored conventionality in the rest of this book. From the moment we meet the first American Lee in 1639 until the moment two hundred and twenty-seven pages later when the newly-promoted Colonel Lee has his climactic meeting with Francis Preston Blair, there is nothing in Korda’s account of Lee’s life which gives a single glimmer of why we should be reading any of this—or yields any clue to what will happen in 1861. Lee served around the country in a military career that spanned thirty years (including a well-applauded stint in the Mexican War), but without, until meeting John Brown, ever operating in combat command. Lee fades so quietly into the background of pre-war American society that it’s no wonder few people in Southern society understood what Jefferson Davis saw in Lee. Ulysses Grant, Abraham Lincoln and William Tecumseh Sherman were, in their pre-war careers, at least extraordinary for their failures. Lee was, by contrast, unfailingly unfailing, and not much more.

Half-sensing this, Korda struggles to inflate Lee’s longest engineering assignment on the Mississippi to one which alters “the course of American history,” although without explaining why Lee’s work did more than alter the course of the Mississippi at two interesting locations. In a nation bubbling with the energies of the nineteenth century market revolution and the warfare between the Whigs and Democrats, Lee was serenely noncommittal; in the midst of the upheavals over slavery, Lee was blandly even-handed until the moment when, on four days’ notice, he became a rebel in arms and tossed aside, seemingly without a word of regret, the loyalties which had guided a lifetime. Never did a slumbering volcano slumber so placidly. Nor for a figure as well-connected by family as Robert E. Lee was do we ever learn very much about his mysterious siblings—about Sydney Smith Lee, who served as a captain in the Confederate Navy; about Charles Carter Lee, who chose to sit out the war on his Virginia plantation; or about Ann Kinloch Lee Marshall, the Baltimore Unionist who never spoke to her famous Confederate brother again after 1861.

Even when Korda’s tempo quickens into the outbreak of the Civil War, the narrative frequently wanders off-focus and into bloated play-by-plays of great battles in which Lee increasingly becomes a Freemanesque “island of calm” whose “serenity of genius” combines the “better qualities of Napoleon with the spirit of Saint Francis of Assisi.” These diversions make for some dismaying imbalances: although Korda devotes fifty-six solid pages to the Seven Days, seventy-seven to Gettysburg, and twelve each to Antietam, Chancellorsville and the surrender at Appomattox, the last five years of Lee’s life at Washington College get only thirteen. Unhappily, Civil War battles are not Korda’s long suit: Lee did not defend “Saint Marye’s heights” at Fredericksburg, Johnston Pettigrew did not go into Gettysburg looking for shoes, Culp’s Hill was not “the key to the situation” at Gettysburg (nor was the famous “clump of trees” located in Zeigler’s Grove), and George Pickett’s complaint in 1870 was not that Lee had destroyed “his regiment,” but his division. (It does not help, either, that Korda thinks the Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed in 1845, or that Northern “doughface” politicians were called doughboys). Korda accepts uncritically the proposition that the Civil War was “the first modern war,” and somehow manages to make the Sunken Road at Antietam contain “the fire bays and traverses of the 1914-1918 trenches.”

Many of these missteps arise from the sheer impossibility of saying anything worthwhile about Lee which is not established on Lee’s private letters and papers, difficult as that prospect is. Not surprisingly, Korda’s notes reveal no effort at archival research. In fact, there are long stretches where, to judge by the notes, Clouds of Glory does little more than re-tread Freeman. And I suspect it is the heavy shadow of Freeman that wears down Korda’s initial resistance to canonizing Robert E. Lee. Indeed, Korda evades the one question about Lee that may be the most interesting: how does one write the life of a man who committed treason? Lee’s own explanation—that his loyalty to Virginia pre-empted his oath to protect and defend the Constitution—has an element of hollowness to it. With unseemly speed, Lee arrived at the conclusion that his Virginia loyalty required him not simply to resign his commission, but also to take up arms against the United States. As Elizabeth Brown Pryor observed in Reading the Man, Lee could just have easily sat the war out as a quiet neutral. After all, Lee spent most of his life in places other than Virginia, and as Gary W. Gallagher has recently reminded us in Becoming Confederates, Lee swiftly became an advocate for centralized Confederate authority through conscription, impressment, and, finally, the enlistment of slaves as soldiers. But Korda makes no effort to question any of this.

The Lee halo precludes, in some minds, even the possibility that what he did was treason at all. The Constitution (which was written by men who, given a few turns of events in other directions, might have been adjudged guilty of treason themselves) does not define treason with very much legal clarity. Further, in an age of aspirations to cosmopolitan attitudes and global interdependence, the concept of treason seems almost offensively medieval. It is, however, the central act and fact of the life of Robert E. Lee. And no biography of Lee will take us very far beyond Freeman until that fact is fully and frankly confronted.

Allen C. Guelzo, a three-time winner of the Lincoln Prize, is the author of Gettysburg: The Last Invasion (2013).