Private Amos Breneman of the 203rd Pennsylvania Infantry was, by his own estimation, an ass. Addressing a male friend back in Lancaster County, he wrote in April 1865, “I am now driving team [and] I have got six mules if you was here you could see a jack ass ride a mule with his pants in his boots.” By war’s end, Breneman’s duties had transformed him into a comedic jack

ass.[2]

Dating to Middle English, ears or arse was used to describe the posterior of both animals and humans; it held a common place in English vernacular with no particular stigma. “Arse-ropes” (intestines) appears in John Wycliffe’s translation of the Bible, while Geoffrey Chaucer’s “The Miller’s Tale” includes a character who longed to have “his arse kissed by this jack-a-nape.”[3]

In the 18th century, the word and its myriad compounds (arse-crawl, arse hole, and kiss my arse) gradually fell out of usage in respectable society and Francis Grose’s Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue rendered it as a-se, discerning that “a lady who affected to be extremely polite and modest would not say ass because it was indecent.” By the mid-19th century the word was deemed completely taboo. In 1888, the Oxford English Dictionary declared arse “obsolete in polite use.”[4]

Civil War soldiers, for the most part, cared or thought little of politeness; they liberally used ass, sh-t, damn, f–k, and other profane words. These moral and prudish Victorians—as we tend to consider them—swore to a degree some may find disconcerting. Not all Union and Confederate soldiers were cussers, nor were they all literate, but many expressed their wartime emotions with strong language.

Civil War officers and chaplains frequently lamented the use of crude language, and it bothered some men in the ranks as well. “Nancy,” a soldier from Ohio wrote in a letter home, “you have but a feint Idea of the wickedness and profanity of the Soldiers. I have been often kept from falling asleep Just by oaths and curses of the worst caracter and perhaps it would be the first thing that would greet my ears when I awoke.”[5]

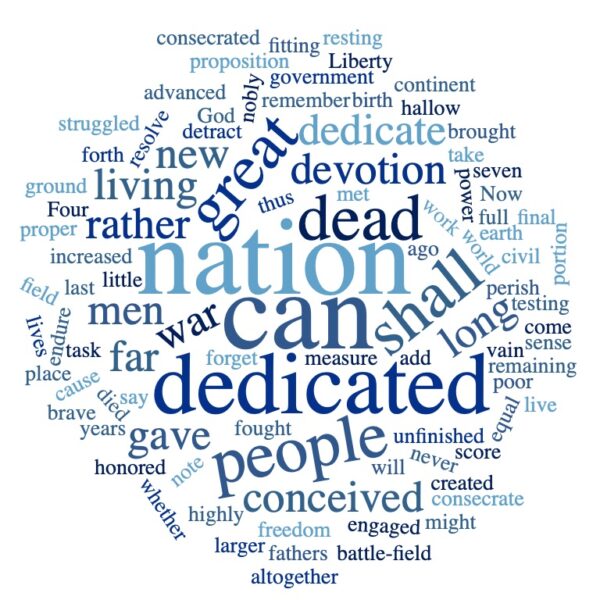

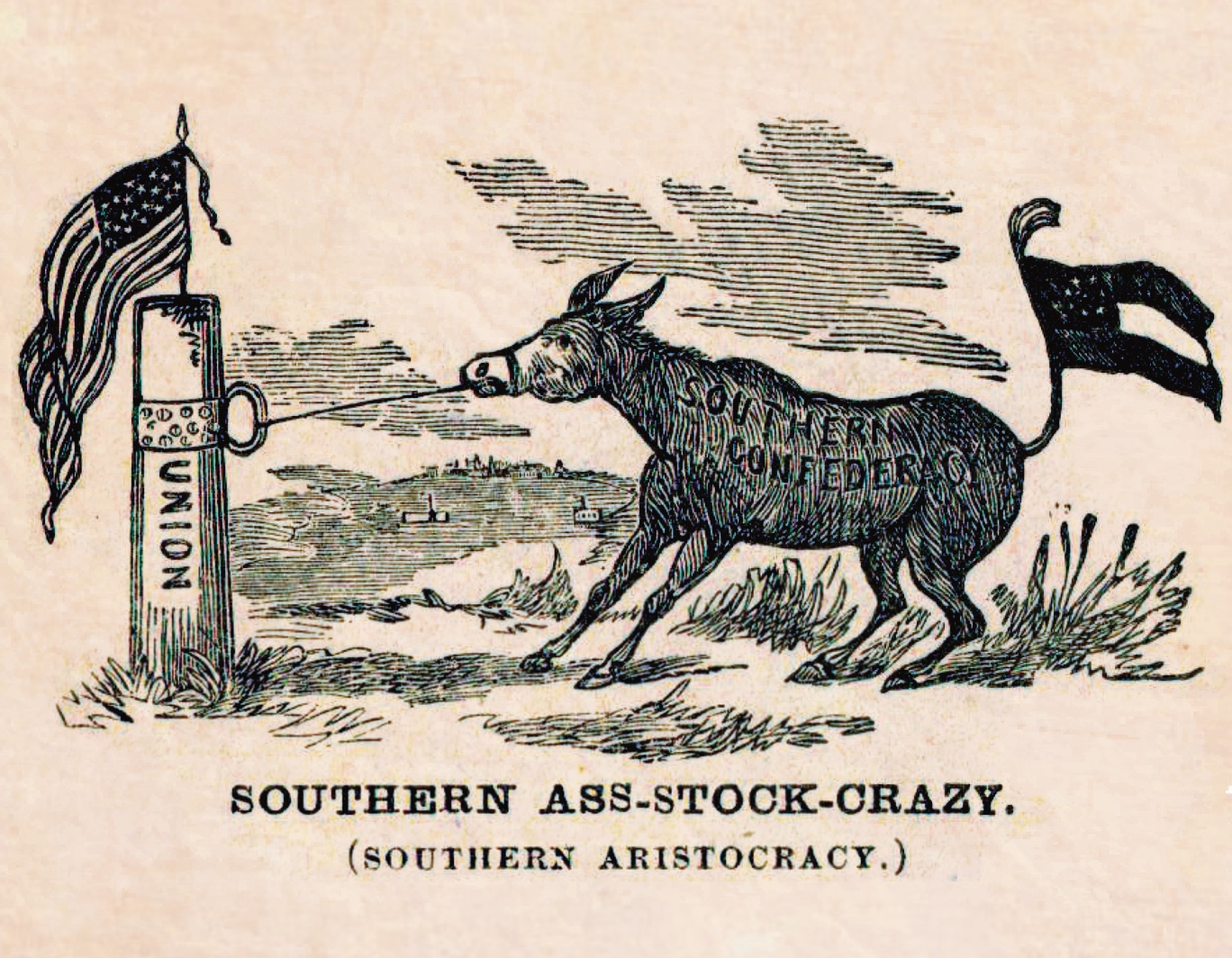

This sketch, printed on an envelope in 1861, depicts the Confederacy as an ass—a word that would be employed in new and creative ways by soldiers on both sides during the conflict.

Civil War profanity, however, was not confined to military men’s speech. Soldiers who verbally swore in camp sometimes used profanity in their letters home, and words such as ass appeared in letters addressed to wives, sweethearts, and mothers. These particular vulgarities were, by their writers’ estimation, simply not that vulgar. Pennsylvania Private Harrison Nesbitt felt comfortable ordering his wife, Jemima, to tell a nosy neighbor “to kiss your ass and mind Her own Business” if she continued to meddle in the family’s financial affairs. Women were not immune to the hardening of their soldiers’ demeanors or their language.[6]

Albinus Fell of the 6th Ohio Cavalry was less figurative in his speech. “I have laid in mud and water and … wet for three days at a time[,] but still I have the same desire to go on until the end and when I am killed I want them [to] roll me in to a hole with my face down so that J.R. Fell can kiss my ass with out turning me over,” he told his wife.[7]

The English had been kissing ass since the Middle Ages, but the American Civil War ushered in a new compound: kick ass. On February 17, 1862, John B. Gregory of the 38th Virginia Infantry wrote, “old capen gilburt is doun her doing All he Can to get us to volenter Agan he Think evry one orter stay.” In between the lines of his letter (above “one orter stay”), he penned “I want to kick ass.” John Boyer of the 190th Pennsylvania Infantry, meanwhile, longed for a letter from his brother, Daniel, but “Dident get no answer yet of him Tell him if he Dont Write soon then i kick His ass when i get home And i am just the boy That can Do it.” These men were determined to do something—win the war, kick the captain, or wallop a sibling. They were going to kick ass! Their unwavering tenacity required a new phrase.[8]

Audience always matters when using profanity, but so too did context, and most usages of ass occurred in comedic moments or passionately determined contexts. The Civil War produced many such instances—from watching a “jack ass ride a mule with his pants in his boots” to being found ass up after dying in combat. The hardship and humor of war shaped all language—the profane included.

TRACY L. BARNETT IS A DOCTORAL CANDIDATE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA. HER DISSERTATION ANALYZES THE HISTORIC ORIGINS OF AMERICA’S GUN CULTURE AND ITS MUTUALLY CONSTITUTIVE RELATIONSHIP TO WHITE SUPREMACIST IDEOLOGY. AS THE DIGITAL HUMANITIES RESEARCH FELLOW, SHE WORKED AS A RESEARCH ASSISTANT FOR PRIVATE VOICES (ALTCHIVE.ORG/PRIVATE-VOICES/), A WEBSITE DEVOTED TO CIVIL WAR LANGUAGE.

1 Noah Webster, An American dictionary of the English Language (Springfield, MA, 1860), 76.

2 Amos Breneman to Abraham Good, April 26, 1865, Private Voices (altchive.org/private-voices/node/13526). 3 Or, in the original Middle English, this character “thoughte he wolde amenden al the jape; He sholde kisse his ers er that he scape.” Geoffrey Hughes, An Encyclopedia of Swearing: The Social History of Oaths, Profanity, Foul Language, and Ethnic Slurs in the English-Speaking World (Armonk, NY, 2006), 12.

4 Hughes, An Encyclopedia of Swearing, 12.

5 Susan G. Hall, Appalachian Ohio and the Civil War, 1862–1863 (Jefferson, NC, 2000), 101. 6 Harrison Nesbitt to Jemima Nesbitt, October 30, 1864, Private Voices (altchive.org/private-voices/node/14009). 7 Albinus Fell to Diana “Mit” Fell, May or June 1862, Private Voices (altchive.org/private-voices/node/13273).

8 The February 17, 1862, letter from John B. Gregory is the first known usage of the phrase kick ass. John B. Gregory to Martha J. Gregory and John Eanes, February 17, 1862, Private Voices (altchive.org/private-voices/node/11901); John Boyer to Peter Boyer Sr., October 7, 1863, Private Voices (altchive.org/private-voices/node/13567).