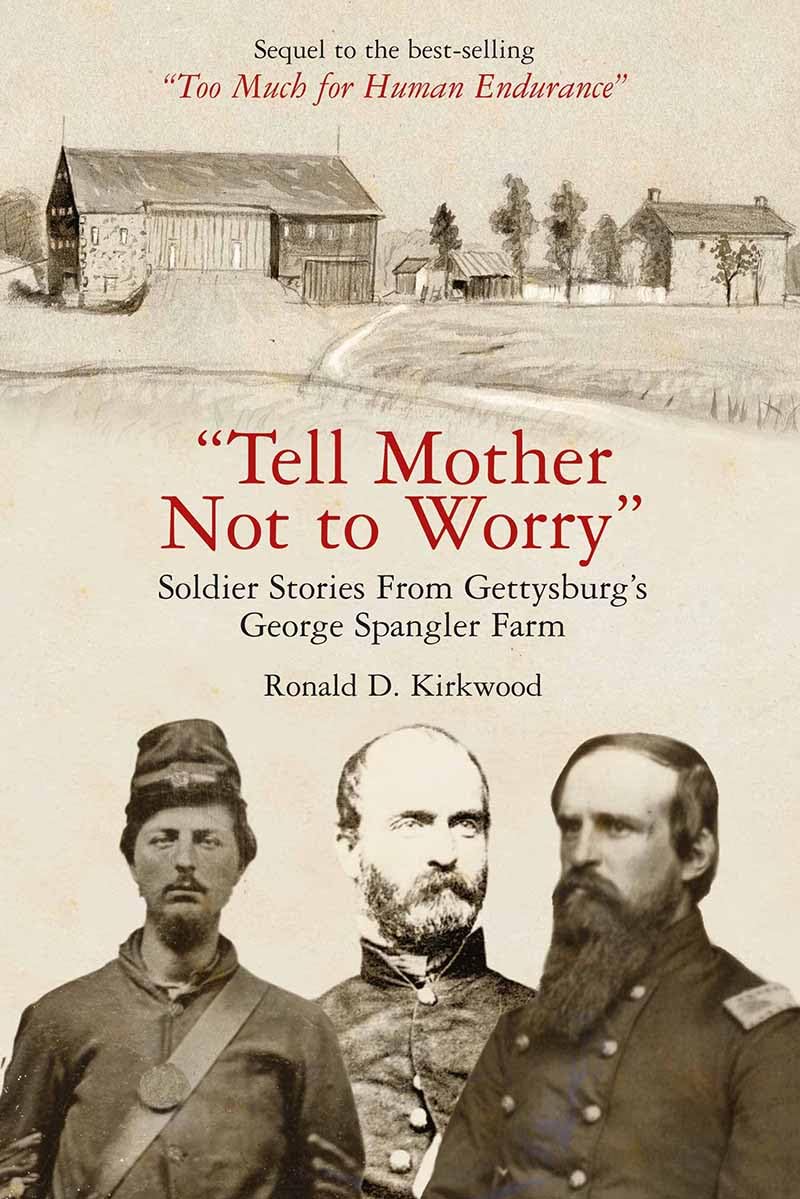

Twenty-five years after the Battle of Gettysburg, a correspondent for the Army and Navy Journal believed that “the literature of Gettysburg has been exhausted.” While that correspondent’s claim was certainly premature, I sometimes wonder with the continued outpouring of books and articles related to Gettysburg if there is anyone who can provide a fresh perspective or deepen our knowledge of one of the Civil War’s most-studied and significant engagements. Ronald D. Kirkwood’s recent volume reminds us that it is indeed possible.

The stories of soldiers treated at the hospital established on George Spangler’s farm are this book’s central focus. While the book contains, as the author freely admits, vivid descriptions of the “sad and gory scenes and smells at the XI Corps and 1st Division, II Corps hospitals,” the book offers readers significantly more (xiv).

Although heralded as one of the Union’s greatest military triumphs, this volume reminds us that for thousands of people, the Battle of Gettysburg prompted little cause for celebration. Kirkwood’s careful analysis of soldiers’ letters and veterans’ pensions powerfully highlights how the fighting at Gettysburg inaugurated a new and oftentimes lifelong struggle—for soldiers who survived their wounds, no less than their family members. For example, Kirkwood recounts the heartbreaking story of Captain Frederick Stowe, Brigadier General Adolph von Steinwehr’s assistant adjutant general and the son of renowned author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Although Stowe survived being struck in the head by a Confederate artillery fragment on July 3, the excruciating pain he suffered troubled him for the remainder of his life. The Stowes attempted all they could to alleviate his suffering, including purchasing a plantation in Florida with the hope that the fresh air would revitalize him. Unfortunately, it did not.

The author’s examination of claims for pensions filed by widows, orphans, and parents reveals much about how loved ones attempted to cope with the loss of their soldier at the front. While oftentimes the process of filing a claim took several months, Kirkwood’s careful study of claims, such as the one submitted by Catharine Getter, the daughter of Private Charles Getter of the 153rd Pennsylvania, shows that the quest for compensation sometimes spanned decades. Born out of wedlock in 1862, Catharine’s quest for a monthly pension lasted until 1907, when she tired of trying. The government repeatedly denied her claim citing that she was illegitimate and therefore not entitled.

Kirkwood’s exemplary study also explores how medical personnel who labored at the Spangler hospital in the weeks after the battle were adversely impacted. Among them was Assistant Surgeon Austin D. Kibbee. The physical strain of caring for the wounded transformed the otherwise healthy thirty-two-year-old doctor into someone deemed “unfit for duty” on August 14, 1863 (81).

Additionally, the author explores Gettysburg’s toll on George Spangler, his wife, Elizabeth, and their four children. Kirkwood rightfully asserts that what happened on the Spangler’s once peaceful farm impacted the “Spanglers for the rest of their lives” (234). Although a paucity of evidence leaves him unable to decisively prove the claim, Kirkwood posits that Daniel, the Spangler’s third child, might have decided to leave Gettysburg several years after the Civil War’s end and head west to Kansas in part to escape the horrors he witnessed in the summer of 1863. Based on the behaviors of others in the war’s aftermath, this theory seems plausible.

This volume’s usefulness is enhanced by brief essays written by medical professionals who offer clear and succinct explanations of the types of wounds and procedures performed at Spangler’s hospital. For example, Dr. Jon Willen, a retired infectious disease specialist, explains the bone resection process, why a surgeon would perform this operation (as opposed to a traditional amputation), and mortality rates in an accessible way.

Kirkwood’s study will undoubtedly appeal to Gettysburg aficionados. However, its utility should extend far beyond students of the conflict’s largest and costliest engagement. Those interested in the long-term impact battle exacts on soldiers and their families will find this exemplary volume informative, powerful, and noteworthy.

Jonathan A. Noyalas is a history professor at Shenandoah University and director of its McCormick Civil War Institute. He is the author or editor of sixteen books, including Slavery and Freedom in the Shenandoah Valley during the Civil War Era and The Blood-Tinted Waters of the Shenandoah.