Library of Congress

Library of CongressThe Battle of Shiloh, as depicted by artist Thure de Thulstrup.

The November 1, 1862, edition of Harper’s Weekly ran a brief article by a member of the editorial staff about the “Dead-letter Office,” a new operation being overseen by an assistant postmaster general in Washington, D.C. The aim of the office, opened in August 1862, was to figure out what to do with soldiers’ letters mailed home but returned to camp as undeliverable, especially when the soldier-authors had been killed since the time of writing. For the war’s first year, such returned missives were destroyed. After the opening of the Dead-letter Office, this class of letters was “examined by a competent clerk, and all that were likely to be of interest or importance again forwarded to the post-offices originally addressed” in a “second effort … to get these soldiers’ letters into the hands of their friends.”

The Harper’s editor had been permitted to view a sampling of these letters (400–500 of which, he was informed, arrived in the Dead-letter Office daily). One of them—written by Lieutenant Colonel Thomas T. Heath of the 5th Ohio Cavalry to the parents of a young Minnesota soldier killed at the Battle of Shiloh—though “very fully and carefully directed,” had “failed to reach its destination,” the Harper’s editor wrote. “[A]nd lest a second effort should prove as fruitless as the first, I am permitted to make an extract, in the hope that it may reach the eyes of the bereaved parents.” It reads:

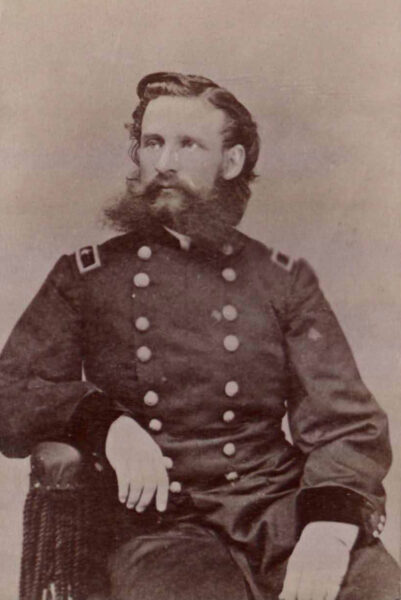

USAHEC

USAHECThomas T. Heath of the 5th Ohio Cavalry

[May 27, 1862

Zanesville, Ohio]

Friends—

On the evening of Monday, April 7, 1862, about five o’clock, after my regiment had been halted in its pursuit of the fleeing hordes of rebels, I rode slowly around the field, meditating on the result of that bloody action, and observing the effect of the “bolts of war” on the dead bodies which covered the ground. Various were the attitudes and expressions of the fallen heroes; yet as I rode along one smooth-faced lad, whose features were lit up by a smile, so attracted and riveted my attention as to cause me to dismount and examine him. His uniform was neat as an old soldier’s, his buttons polished, his person clean, his hair well combed, lying squarely on his back, his face toward the enemy, his wounds in front, from which the last life-drops were slowly ebbing, his hands crossed on his breast, and a peaceful, heavenly smile resting on his marble features. I almost envied his fate as I thought,

“How sleep the brave who sink to rest,

By all their country’s wishes blest!

* * * * * *

By fairy hands their knell is rung,

By forms unseen their dirge is sung;

Lo! Honor comes, a pilgrim gray,

To bless the turf that wraps their clay,

And Freedom shall a while repair

To dwell a weeping hermit there!”

I asked the by-standers who that lad was. No one could tell. Hoping to find some mark on his clothing by which I could distinguish him, I unbuttoned his roundabout, and in the breast pocket found a Bible, on the leaf-fly of which was an inscription by his mother to “John Elliott.” In the same pocket was a letter from his mother, and one he had written to his uncle, both dabbled with blood. Pleased with getting these data from which to trace his family, I determined to preserve the Bible and letters and send them to you. I have since regretted that I did not examine all his pockets and save whatever may have been in them; but my time was short, and I felt that the Bible he had so faithfully carried would be treasure enough for you, and in the hurry of the moment I did not think to look for any thing else. His remains received decent sepulture that night, and he now sleeps in a soldier’s grave.

And now, dear friends, I would have written to you weeks ago, but was long sick in camp, was sent to Ohio low with fever, and am but just able to begin to sit up.

You have doubtless wept over your dead boy. No human sympathy could assuage your grief. Yet He who guides and governs the universe of man and matter, I doubt not, has thrown around you “everlasting arms,” and supported your faint, bereft, and bleeding hearts.

After a while, when time shall have healed the wounds the war has inflicted, it will be a heritage of glory for you to reflect that your boy died in the cause of human rights and to save the life of a great nation; and you can with righteous pride boast that he fell in the thickest of the fight, with dead rebels all around him, his face to the foe, and in the “very forefront of the battle.”

He died a young hero and martyr in the holy cause of freedom, and Elijah riding up the heavens in a chariot of fire had not a prouder entrance to the Celestial City than your boy. Let your hearts rejoice that there is one more waiting to welcome you back to the “shining shore.”

Heath, who wrote the Elliotts while recuperating from sickness at his Ohio home, was promoted to colonel of the 5th Ohio Cavalry in August 1863. He was promoted to brigadier general in December 1864 and mustered out of the service in October 1865. He died in October 1925 at age 90. It is unknown whether Heath’s letter was ever properly delivered.