The term radical originated with the Latin radix, or source, and it has always had popular connections with the steely determination to tear-up obnoxious ideas or movements by their roots. It came into nineteenth-century American political usage as the term to describe Martin Van Buren and the “Radical Democracy” of 1848. But it became the favorite adjective of the most uncompromising anti-slavery exponents of the new Republican Party after its founding in 1854. From there (and for the next twenty years), Radical Republican became a way of describing the most ultra faction of Republicanism’s anti-slavery cohorts.

But only the most ultra. The Republican Party was, like the anti-slavery movement itself, a coalition that emerged from the wreckage of the old Whig Party, and it embraced an argumentative spectrum of nativists, anti-slavery Northern Democrats, Northern Whigs, and outright abolitionists. They were agreed on only one point – opposition to the spread of slavery into the western territories – and on every other political issue, from tariffs to banking, fell almost at once into quarrels. It is a measure of how threatening, and how aggressive, slavery was in the 1850s that opposition to its spread sufficed to keep these disparate interests together. And not only kept them together, but enabled them to capture the presidency on only their second try, in 1860.

Nevertheless, the Radical Republicans have always been the most colorful of the party’s factions to chronicle. They have enjoyed both outstanding group histories and individual biographies. And with LeeAnna Keith’s new When It Was Grand, we are presented with a bridge built from the Radical Republicans of the Civil War era to modern progressives in the 21st century.

For Keith, the Radicals were a forerunner of intersectionality, a Victorian version of the woke. And they provided the energy which transformed the uncertain purposes of the Republican Party with the drive that generated a direct confrontation with slavery and, ultimately, the Civil War. The Republicans thus became a forum which, guided by the Radicals, “brought together men and women, whites and blacks, poets, philosophers, captains of industry, and extremists of many political stripes” (3). “Ballooned into existence” by outrage over the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the Radicals recognized that “the tremendous latent power of the state…could be seized and used to accelerate the bend toward justice in American life” and sought to incite the Republican Party to use it (44).

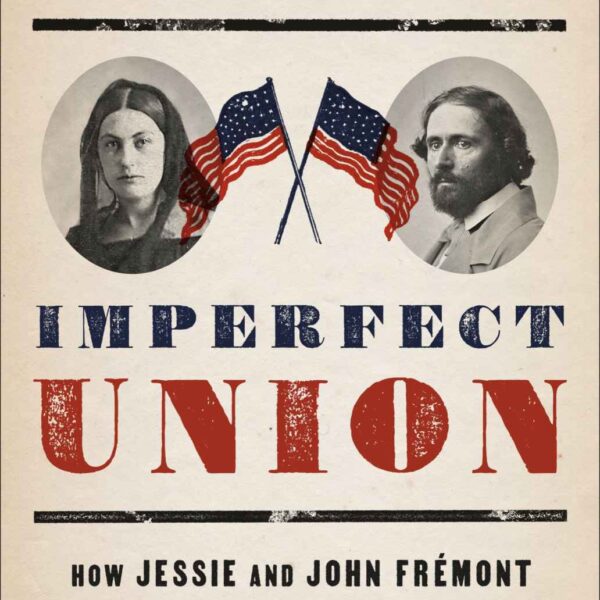

This would have been a remarkable transformation of the Party’s purposes, if Keith could have provided some hard evidence of it. (It was, in fact, the complaint of many Republicans that it was the “Slave Power” which had hijacked the “power of the state” for its version of “justice”). There was no census of the Republican Radicals, not even the most informal organization, and so it is not clear who acted upon whom, and to what end. Keith’s reckoning of who the Radicals were, exactly, is uneven at best. Clearly, her favorite Radical is John Brown; yet Brown wanted nothing to do with the Republicans. Her other Radical heroes are presented with the same absence of rationale: Theodore Parker, but not Thaddeus Stevens; Jessie Benton Fremont but not Owen Lovejoy; George Stearns but not Zachariah Chandler or Ben Wade. Elizabeth Cady Stanton is lionized, but her racist spat with Frederick Douglass over the 15th Amendment is ignored. This is, in other words, celebration more than history, and highly selective celebration at that, with any unfortunate departures from modern sensitivity obligingly erased, and all couched in a happy-clappy style which befits middle-school story-time better than the complexities of real historical narrative.

It will not, on those terms, come as surprise that Keith has small patience with Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln, says Keith, “prayed before the flawed godhead of the U.S. Constitution, recognized property in slaves, and freely floated racist epithets and stereotypes in private and in public remarks” (88). He was at best a “centrist” who “advocated a broader, philosophical kind of Radicalism” (99) and a promoter of “party unity above all” (115). She scorns Lincoln’s Cooper Institute speech for not containing “a whisper of the far-left agenda” (116) and scorns the Emancipation Proclamation, as well, since it “would result in the emancipation of practically no one” (167). Readers may judge for themselves whether the Constitution is a “flawed godhead” that people pray to; but there is no evidence that Lincoln ever recognized “property in slaves.” And far from emancipating “practically no one,” the Proclamation declared the legal freedom of at least three million people. This is carelessness on a rapid-fire scale, and it runs-up directly against Frederick Douglass’s description of Lincoln as “emphatically the black man’s president.”

Keith’s carelessness shows up in a number of other ways, too. She mistakes John Bingham for Kinsley Bingham (93), claims that Robert E. Lee commanded “the militia” at Harpers Ferry (he didn’t; he commanded a single company of U.S. Marines) (102), and believes that Nathaniel Lyon was killed by “the new technology of soft bullets” (bullets had been “soft” since hand-held firearms were first introduced) (143). It should be said, too, that the gunboat Indianola was not “an 1862 model ironclad battleship” (204), much less a “monitor,” that the massacre of black fugitives at Ebenezer Creek did not occur because “civilians had been trapped on an exploding bridge” (it was because Gen. J.C. Davis’s engineers deliberately cut loose a pontoon bridge that isolated the fugitives on the Confederate side of the creek) (284), and that the Freedmen’s Bureau was established in March 1865, not 1864 (256). And we would certainly like to know how Keith discovered that the Mississippi river valley was “where slaves deserted by the millions” (217), since the best estimate Secretary of State Seward could offer in 1865 for the number of slaves who deserted the entire Confederacy during the war was 200,000.

These objections, however, are beside Keith’s ultimate point, which is to indict the Republican Party for failing to follow the Radicals’ lead into the postwar decades. “Though the Republican Party boomed in the post-reconstruction era, the radical humanitarian faction lost momentum and influence,” Keith explains. Hence, ‘it proved easy for white Republicans to…surrender the fight for black civil rights in favor of more certain or more popular objectives.” (291) This would have come as surprise to the Republicans who promoted civil rights initiatives straight through the rest of the century; if they lost “momentum,” it was because they lost the House of Representatives in 1874, the Senate in 1878, and the presidency in 1884. But this requires a willingness to confront complexity with which When It Was Grand is not particularly patient. Reading it may give plenty of fizz, but not much body.

Allen C. Guelzo is Director of the Initiative in Politics and Statesmanship at Princeton’s James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions.