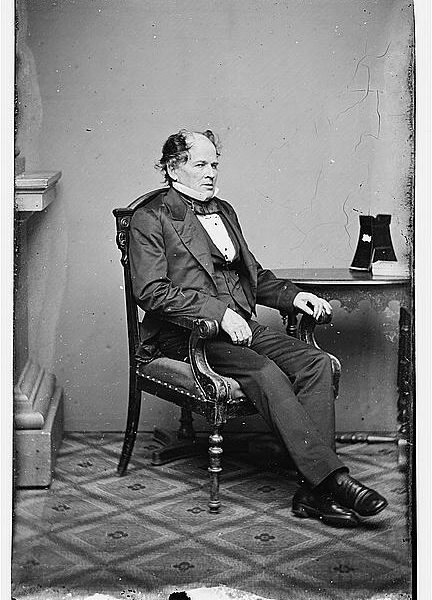

John Sherman was a rising Republican star. A prominent member of the U.S. House of Representatives, he was on the cusp of a long Senate career. Everyone knew the man was competent, but many found him cold, and that ultimately would thwart his presidential hopes. As his derisive nickname suggested, the “Ohio Icicle” might have failed the modern “beer test,” just like Al Gore. But all this lay in the future. The big story in November 1860 was someone else’s election to the presidency.

Sherman, who considered himself a “moderate conservative,” hoped the South would come to its senses after Abraham Lincoln’s election. “You were long enough in Ohio and heard enough of the ideas of the Republican leaders,” he pointed out to his soon-to-be-famous brother, William Tecumseh Sherman; you “know very well that we do not propose to interfere in the slightest degree with slavery in the States.”1

But Republican disavowals were almost universally ignored or spurned in the Deep South. It became an article of faith there that Republicans were abolitionists in disguise. By preventing the expansion of slavery, it was argued, they would begin its slow strangulation, and they might even covertly support John Brown-type raids along the border. So South Carolina and the six other Deep South states decided to break up the Union rather than accept the results of the presidential election. By early January 1861, a grave crisis threatened to erupt into civil war.

Sherman must have squirmed as he read the belligerent pronouncements that filled his morning mail. Many of his home state correspondents implored him to share their passion. They pronounced themselves “stiff as iron” and furious at traitors. “Stand square to the line and if war and blood must come let the blood guilt . . . rest upon those who brought the country to this pass,” one advised him. They also provided heavy-handed reminders of the political stakes involved. They beseeched Sherman to “stand firm” and to show “back bone.” No public man who “betrays the cause of Freedom and Humanity in the hour of need” had any political future.2

But Sherman was conflicted. Unlike his constituents with itchy trigger fingers, Sherman feared that war would make a bad situation far worse. He knew that in the Upper South “a large class of true sincere Union men” deplored as much as any northerner “the madness and wickedness of the disunionists.” They appealed to Republicans “to give them aid and comfort and to strengthen their hands.”3

So what would Sherman offer the Upper South? His speech on January 18, 1861, centered around two key proposals. First, in order to dispose of the divisive territorial issue, he would admit the New Mexico Territory into the Union as a state. It was the one remaining territory south of 36°30′, the old Missouri Compromise line. And the New Mexico Territory had a slave code.4

Second, and of more importance here, Sherman spoke out on behalf of a constitutional amendment forbidding the federal government from ever interfering with slavery in the states where it already existed. At first Sherman was surprised to find the subject even being discussed. He assumed it was “an axiom of American politics” that the federal government had no such power. But he had come to realize that many in the South actually believed “the oft-repeated assertion” that Republicans intended “to interfere with slavery in the States.” He wanted “to convince the South that what has been so often stated . . . was not truly stated.”5

A private and poignant exchange of letters with a former colleague reminded Sherman how grave the North-South breach had become. Nathaniel Greene Foster, an “old line Whig” from Madison, Georgia, had run on the American party ticket and served with Sherman in Congress from 1855 to 1857. They “sat side by side for a whole session,” and had “the highest regard for each other.” Four years later, however, Foster was convinced that southern slaveholders would “gradually, but surely” be deprived of their property. He recognized that Republicans promised they would “not attack the institution in the states directly,” but he accused them of planning “to arrive at the same result by indirect action.” The people of Georgia would not “tamely submit to it” and would fight instead. “If we are to be destroyed we prefer not to go by inches.”6

Sherman attempted to reassure Foster that he misunderstood the Republican party, but the Georgian insisted that Sherman and other moderates would not be able to “hold the feeling of fanaticism in check.” Foster was convinced that Republicans were ready to “wink” at impulses that ultimately would “set the slaves upon our women and children.”7

In retrospect, of course, Sherman attempted the impossible. He and other moderate Republicans did mastermind the successful push to get two-thirds of both houses of Congress to accept the would-be Thirteenth Amendment, which specified that “no amendment shall be made to the Constitution which will authorize or give to Congress the power to abolish or interfere, within any State, with the domestic institutions thereof, including that of persons held to labor or service by the laws of said State.” Sherman hoped to demonstrate to the South that his party rejected the abolitionist agenda.8

But southern absolutists grossly exaggerated the danger that slaveholders faced in the Union and depicted Republicans as the abolitionists that they were not. Secessionists thereby created a monster that owed its existence to their own exertions. Abolition became possible only because secessionists removed their states from the Union, ignored the last-minute peace offering, and chose to go to war.

Once the war started, it grew to enormous proportions and eventually acquired a revolutionary agenda—to end slavery. Four years and one war later, Congress would approve a very different Thirteenth Amendment—which abolished slavery. But without the war that secessionists brought upon themselves, slavery would have lived on.

Dan Crofts, Professor of History at the College of New Jersey, has published widely on the antebellum South and the sectional crisis, including A Secession Crisis Enigma: William Henry Hurlbert and “The Diary of a Public Man,” and Reluctant Confederates: Upper South Unionists in the Secession Crisis. He is currently working on a history of the would-be Thirteenth Amendment.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division: www.loc.gov.

1John Sherman to William Tecumseh Sherman, 26 Nov. 1860, 22 Dec. 1860, http://www.familytales.org/dbDisplay.php?id=ltr_jos1650&person=jos and http://www.familytales.org/dbDisplay.php?id=ltr_jos1652&person=jos

2W. F. Panam to Sherman, 1 Jan. 1861, H. C. Johnson to Sherman, 1 Jan. 1861, A. P. Stone to Sherman, 7 Jan. 1861, Z. Phillips to Sherman, 10 Jan. 1861, all in the John Sherman Papers, Library of Congress.

3James T. Hale to Abraham Lincoln, 6 Jan. 1861, The Robert Todd Lincoln collection of the papers of Abraham Lincoln, LC. Hale, like Sherman, was a member of the so-called Border State Committee.

4Congressional Globe, 36th Congress, Second Session, 455. Sherman might have been willing to bend a little more toward the South. James T. Hale of Pennsylvania, Sherman’s Republican colleague on the so-called Border State Committee, had floated a trial balloon that would have barred Congress from legislating against slavery in the New Mexico Territory—in effect re-establishing the Missouri line—but Lincoln firmly quashed this potential concession to Southern sensibilities on the territorial issue. New Mexico statehood was a scheme to bypass the territorial tangle. See Lincoln to James T. Hale, 11 Jan. 1861, in Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 9 vols. (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1953-55), IV:172.

5Congressional Globe, 36th Congress, Second Session, 454.

6Nathaniel G. Foster to Sherman, 10 Jan. 1861, Sherman Papers, LC.

7Nathaniel G. Foster to Sherman, 21 Jan. 1861, Sherman Papers, LC. This letter alludes to a response from Sherman.

8Congressional Globe, 36th Congress, Second Session, 1285, 1403. Majorities of Republicans voted against the amendment in both the House and the Senate, but it never would have seen the light of day without the sponsorship of moderate Republican leaders, including Thomas Corwin, Charles Francis Adams, and William H. Seward, together with Sherman.