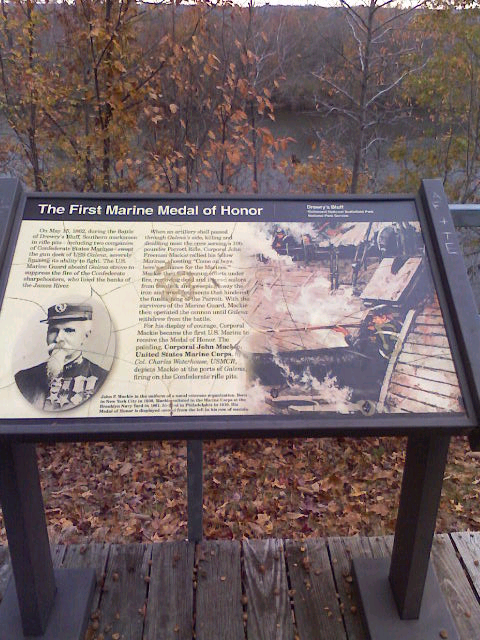

One rarely thinks of the United States Marine Corps and the Civil War in the same thought. Given their small size and limited service, this is not really surprising. And yet hidden away in a rarely visited section of the Richmond National Battlefield Park—Drewry’s Bluff—sits an interpretative marker honoring Corporal John F. Mackie. (At least the marker was there five years ago.)

As any marine can tell you, Mackie was the first leatherneck to merit the Medal of Honor. During the Battle of Drewry’s Bluff, and specifically the attack on Fort Darling, Mackie served as part of the USS Galena’s Marine Guard. After the demise of the ship’s entire Third Division of IX-inch Dahlgren Guns and 100 Pound Rifles, Corporal Mackie rallied the Galena’s Marine Guard into action, defending the ship from Confederate gunfire. For his heroics, Captain John Rodgers, commander of the Galena, recommended Mackie to the Secretary of the Navy. The official order read, “While serving on board the U.S.S Galena, in the attack on Fort Darling, at Drury’s Bluff, James River, May 15, 1862; particularly mentioned for gallant conduct and services and signal acts of devotion to duty.”1 Mackie actually received the Medal of Honor a year later while stationed aboard the USS Seminole. During the presentation Commodore Percival Drayton reportedly stated, “Sergeant I would give a stripe off my sleeves to get one of those in the manner as you got that.”

Fast forward 150 years and present day visitors to the aforementioned interpretative marker are struck by the dual visuals: the marker itself (with the detailed text, a portrait of Mackie, and a vivid depiction of the action aboard the USS Galena) and the breathtaking view of the James River. The marker is situated atop Drewry’s Bluff and overlooks the area where Mackie and the Galena crew exchanged fire with the entrenched Confederates. Enhancing the visual elements is an audio feature that recounts the heated action between the Union and Confederate Marines on May 15, 1862.

Even more striking is the background behind the marker. William R. Gibbs, a Civil War Marine living history volunteer, proposed the project. Troubled by the previous lack of commemoration of such “holy ground,” Gibbs claimed that the marker would “give Marines a place to connect with their history.”2 Private donations from the Marine Corps League and retired marines helped to fund the marker and it was dedicated on the 138th anniversary of the Battle at Drewry’s Bluff (May 15, 2000). In essence, the marker truly is of, by, and for the Corps. More poignantly, this commemorative marker allows marines to interact with their shared past and directly engage their collective memory. It reminds us that a single member of a community can effect a change that impacts the collective memory of an entire group…and that it is never too late to step forward and honor a Civil War hero.

Ultimately, this unique commemoration to a Civil War Marine serves as a cross between a traditional commemorative monument and a “prosthetic memory.” (Alison Landsberg defines prosthetic memory as one that “emerges at the interface between a person and a historical narrative about the past, at an experiential site such as a movie theater or museum;” a memory that can interact with an individual and allow that person to take “on a more personal, deeply felt memory of a past event through which he or she did not live.”3 ) Given that marines can literally see, hear, and feel this commemoration, the marker is a prime example of an experiential form of commemoration. The prosthetic nature of the marker allows marines to physically interact with the events surrounding May 15, 1862 and tangibly connect with their collective memory of the heroism and Civil War action of John Mackie. And for us non-service members, the marker is a great way to learn about the Civil War while retracing the steps of one its many heroes.

Notes:

1. Available at http://www.tecom.usmc.mil/HD/PDF_Files/MOH%20Citations/Mackie,%20John.pdf courtesy of the USMC Training And Education Command.

2. J.B. Walker, “Here’s a Chance for the Marines,” Leatherneck 84, no. 2 (February 2001): 41.

3. Alison Landsberg, “Introduction: Memory, Modernity, Mass Culture” in Prosthetic Memory: The Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), 2.

Image Credit: Author’s private collection.