In October 1859, abolitionist John Brown led a raid on the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in hopes of obtaining the necessary weapons to arm a successful slave insurrection throughout the region. The raid failed, and by year’s end Brown was dead, hanged after being convicted of treason and inciting slave insurrection. The impact of his actions would live on, however; Brown remained a symbol of the danger posed by abolitionists in the South, while he was considered a martyr throughout much of the North. Shown below are images associated with Brown and his fateful raid.

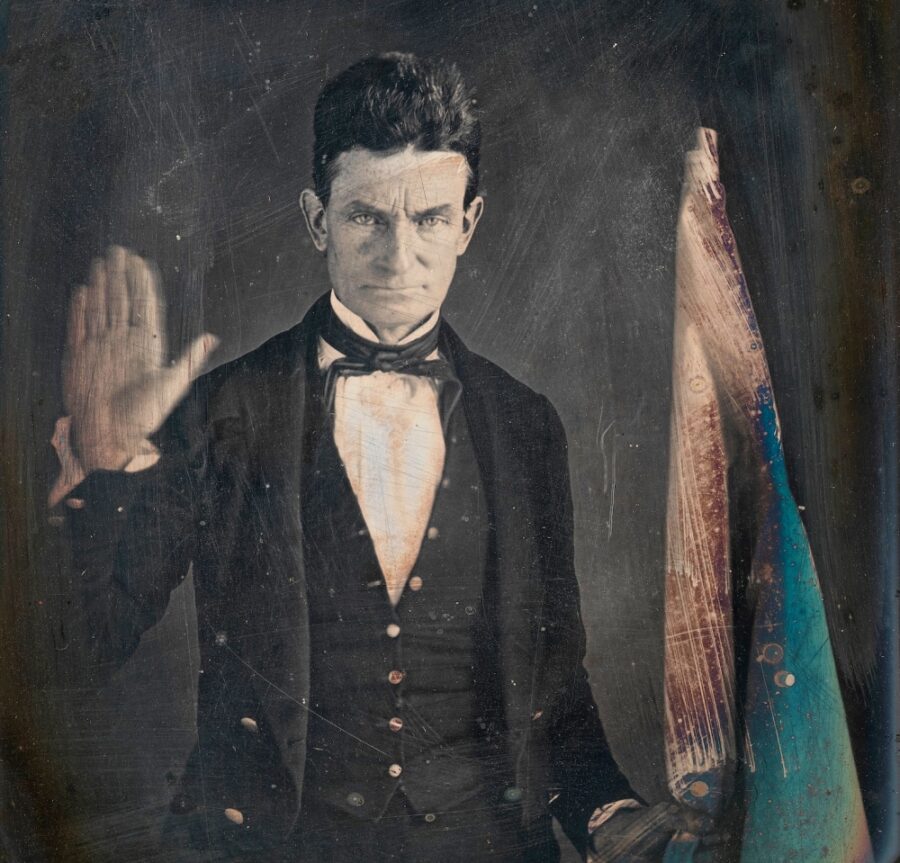

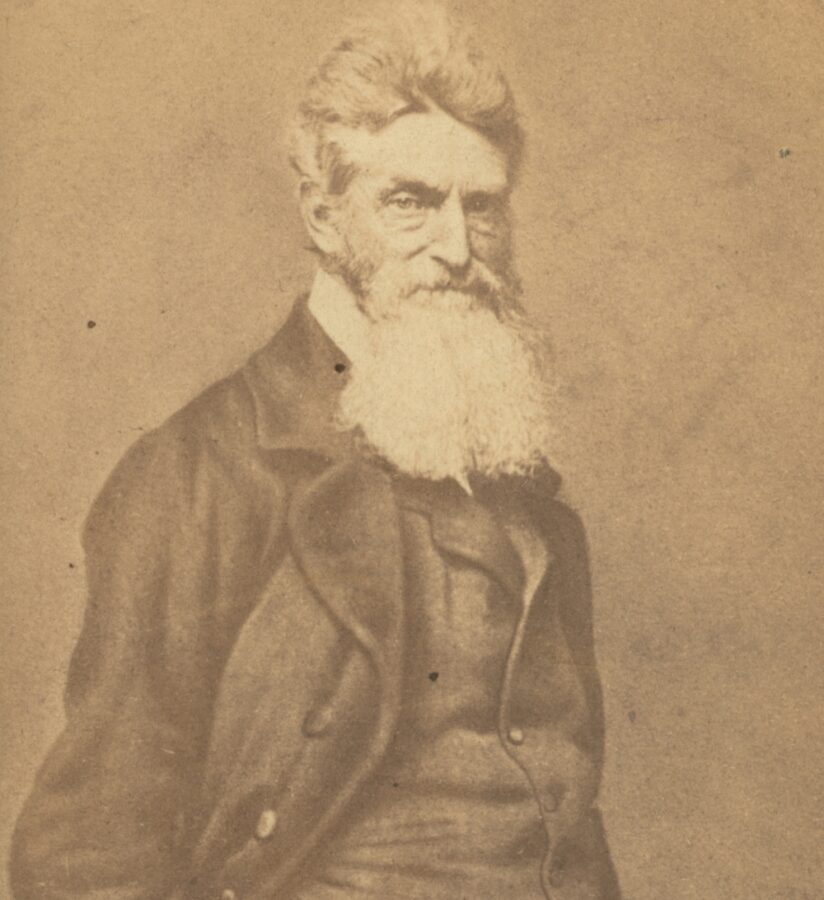

Born in 1800 in Connecticut, John Brown grew up in an antislavery household in Ohio (his father offering the family home as a safehouse on the Underground Railroad). He would marry twice, in 1820 and 1833, and father 20 children, not all of whom survived to adulthood. In 1846, Brown moved to Springfield, Illinois, where his abolitionist feelings became more fervent. He’d move again, first to New York, then to Kansas, where he and other likeminded settlers hoped to bring the state into the Union slave-free. In May 1856, Brown and other abolitionists attacked and killed several pro-slavery settlers in what became known as the Pottawatomie massacre, which ushered in a bloody phase in “Bleeding Kansas” history. Above: Brown as he appeared 1846 or 1847 during his time in Springfield. He is holding the flag of Subterranean Pass Way, his militant version of the Underground Railroad. (National Portrait Gallery)

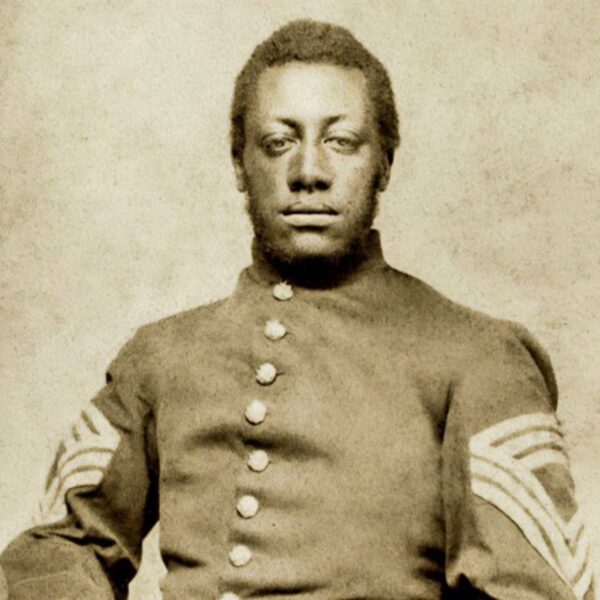

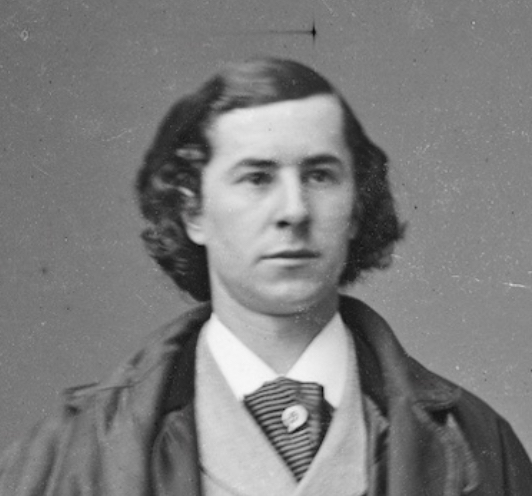

Brown returned to New England in 1856, raising funds for the abolitionist cause and making influential friends in the movement, six of whom—known as the Secret Six—pledged to help finance Brown’s antislavery activities. Over the next few years Brown traveled throughout several northern states to continue to raise funds and garner support, in particular for his plans to recruit men—in particular former slaves—for an attack on slaveholders in Virginia. Above: Brown as he appeared in May 1859, five months before the raid on Harpers Ferry. (Library of Congress)

On October 17, 1859, Brown and his band of 21 men—16 white and 5 black—armed with Sharps rifles and pikes advanced on the federal armory in Harpers Ferry (shown here in 1862). Brown planned on siezing its thousands of rifles to arm area slaves before heading south, growing his army as they moved across the state. (National Park Service)

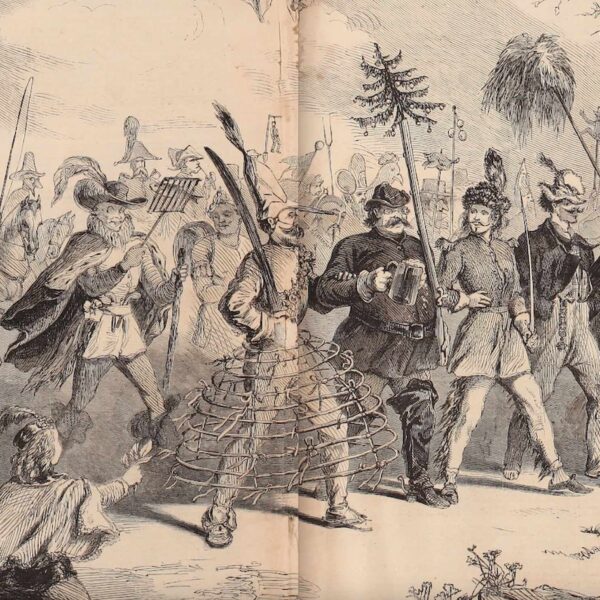

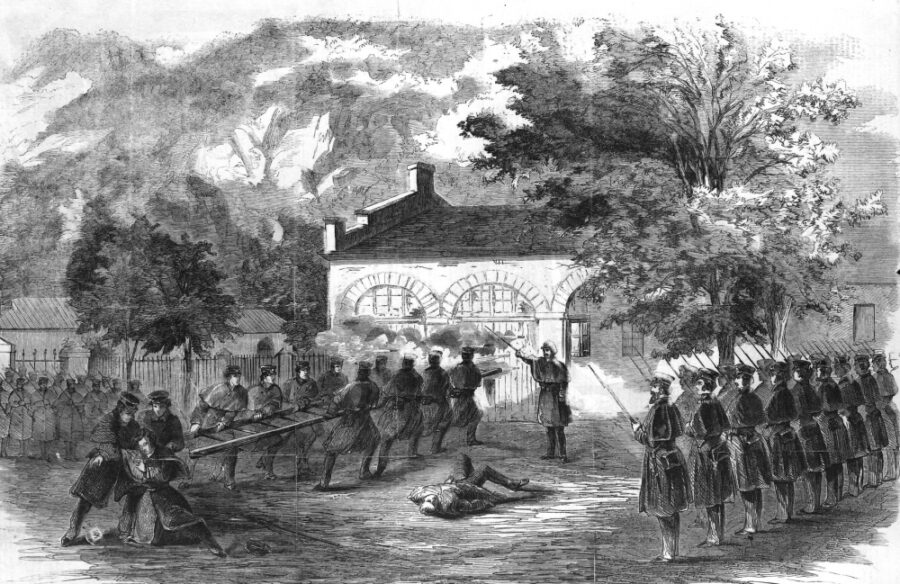

While Brown’s raid started well—he and his men met little resistance in town and successfully siezed the armory—word of his actions were soon telegraphed to Washington. Soon, armed locals and militia pinned down Brown and his band, who soon took shelter in the armoy’s brick engine house. By the morning of October 18, a company of U.S. Marines, under the overall command of Colonel Robert E. Lee, had surrounded the engine house, as depicted here in a sketch from Harper’s Weekly. (Library of Congress)

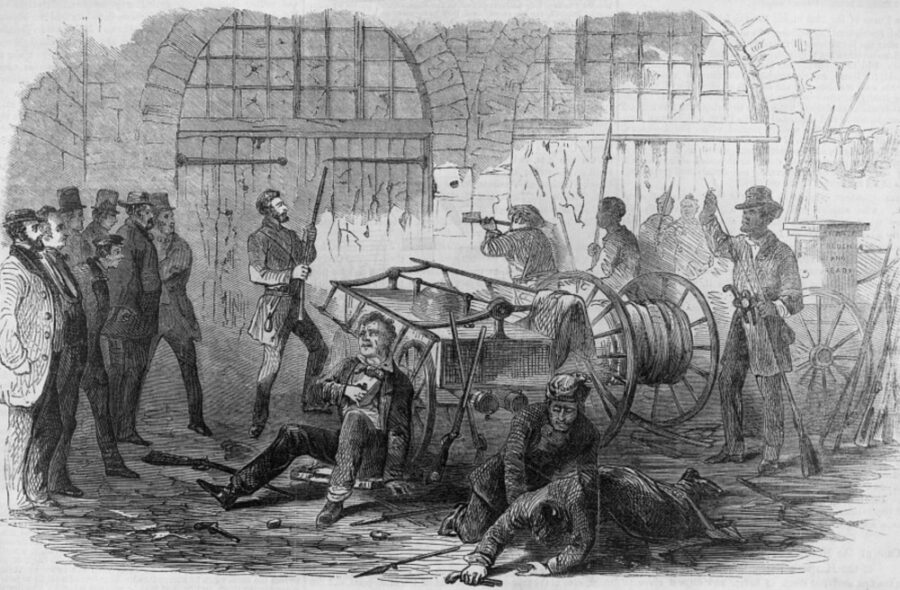

Brown and his men were no match for the Marines, who eventually broke down the engine house’s door and charged into the building. By the time the fighting was over, Brown had been wounded in the head and 10 of his men had been killed, including two of his sons. Brown’s men had killed four and wounded nine. Above: Brown and his raiders fight it out in the engine house as a group of prisoners they had taken in town stand at left. (Library of Congress)

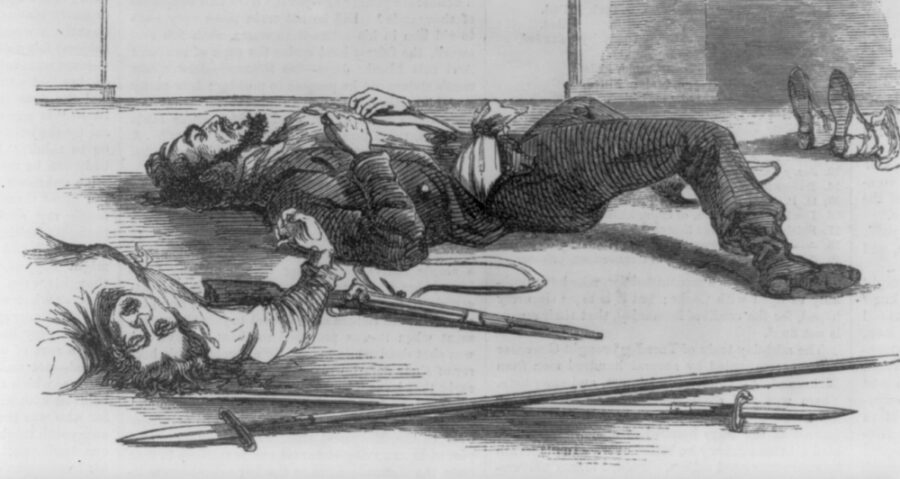

Harper’s Weekly illustrated this sketch of the aftermath of the fighting with the following caption: “Brown, his son, and other of the outlaws awaiting examination.” (Library of Congress)

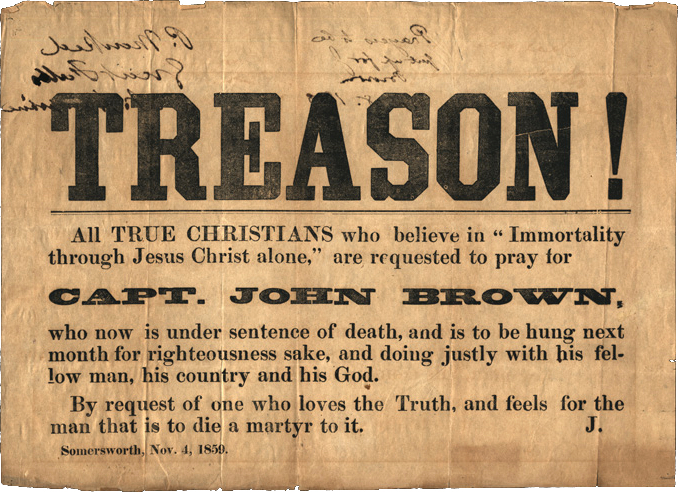

Though Brown’s attack had occurred on federal property, Governor Henry Wise successfully lobbied to have the abolitionist tried in Virginia. The week-long proceedings began on October 27; on November 2, the jury (having deliberated for less than an hour) found Brown guilty on all three counts he was charged with: murder; inciting slave rebellion; and treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia. The news quickly spread throughout the country, the reaction to Brown’s sentence varying widely between the North and South. Above: A broadside published on November 4 in Virginia carries news of Brown’s fate. (Library of Virginia)

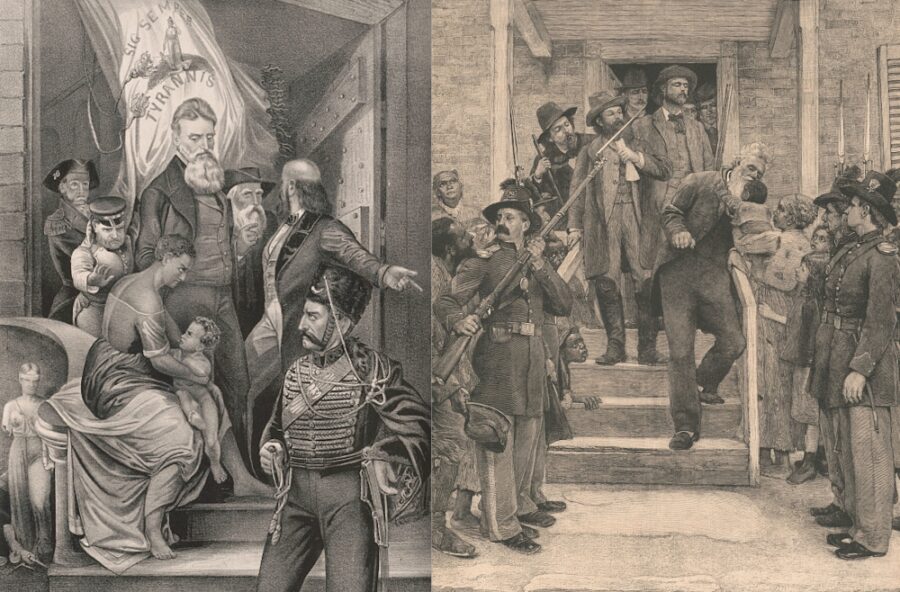

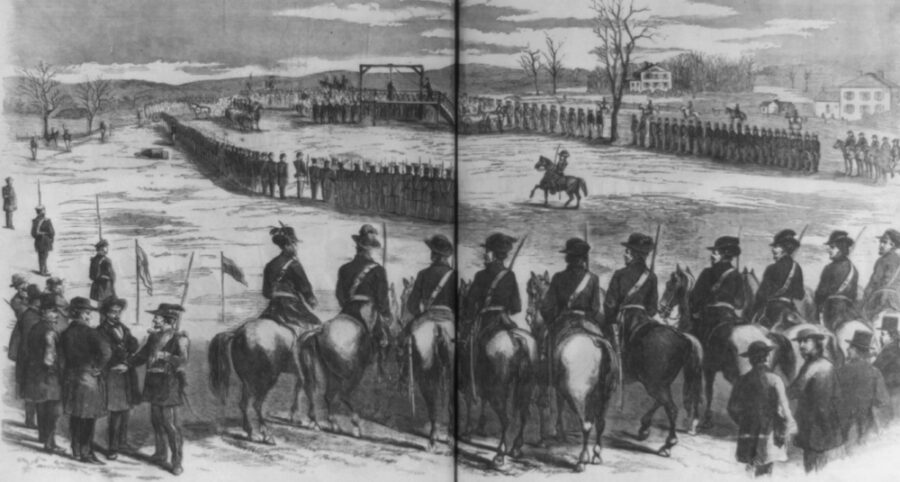

On December 2, Brown was escorted from the jail in Charles Town (as depicted in these two postwar illustrations) and taken to the site of his execution. That morning, he had written down his final words: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed it might be done.” (Library of Congress)

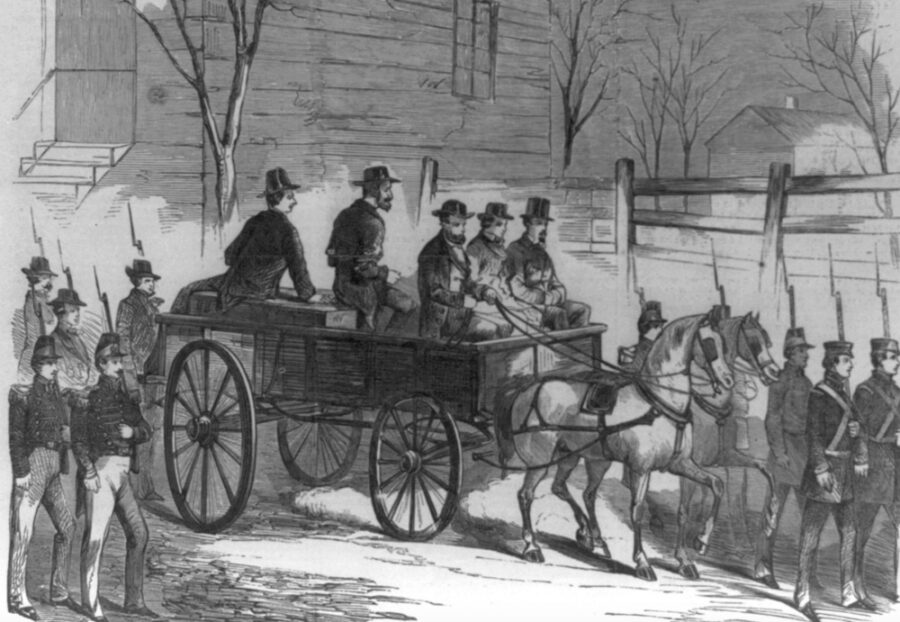

Brown was transported to the gallows a few blocks away from the jail on a furniture wagon, sitting on his coffin, as depicted above in a sketch from Harper’s Weekly. (Library of Congress)

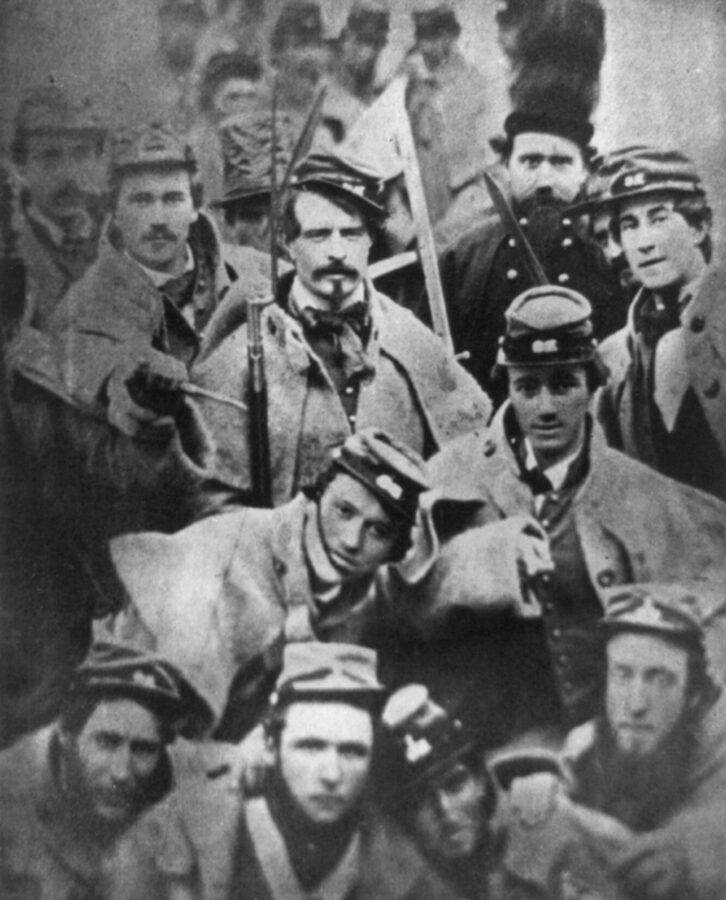

Along the way, Brown passed a crowd of some 2,000 soldiers crowded along his route, including militiamen from the Richmond Grays (shown above in a photo taken on the day of the execution) and several prominent future Confederates, among them Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. (Library of Congress)

Brown was hanged at 11:15 a.m. and pronounced dead roughly 30 minutes later. His body, the noose still around his neck, was placed into the coffin and sent via train for burial in New York. Brown was hailed in the North as a martyr and villified in the South. Little over a year later, the bloody civil war Brown predicted would befall the nation became a reality. (Library of Congress)

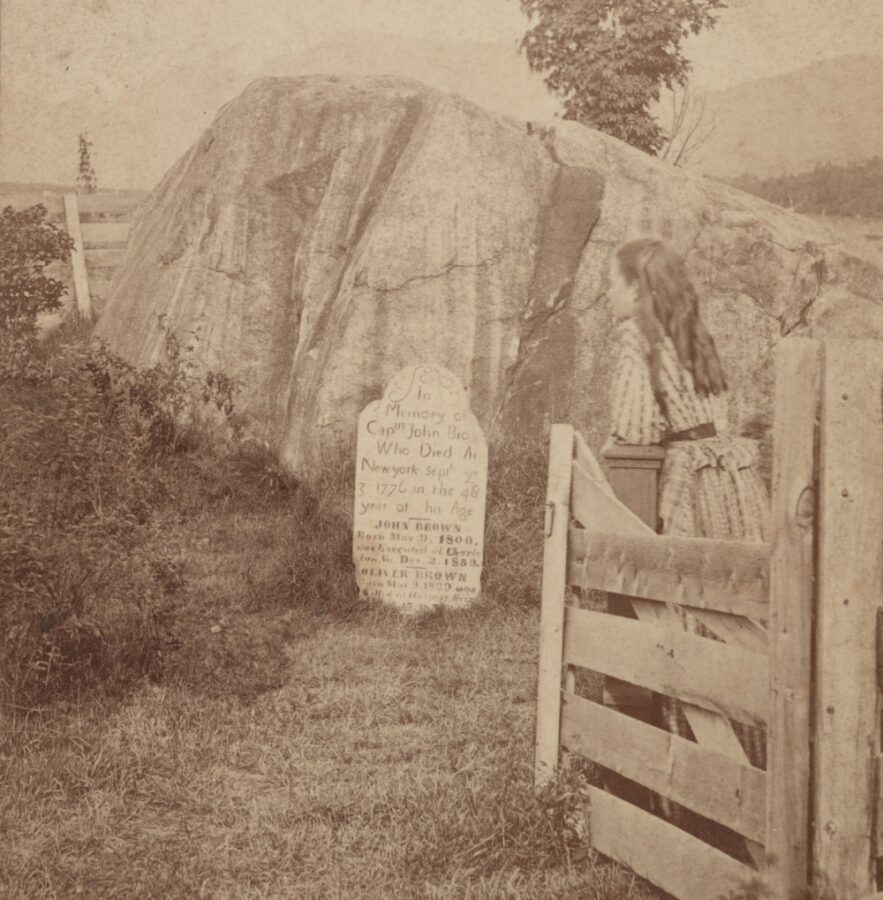

Writing of Brown after the Civil War, Frederick Douglass noted, “His zeal in the cause of my race was far greater than mine—it was as the burning sun to my taper light—mine was bounded by time, his stretched away to the boundless shores of eternity. I could live for the slave, but he could die for him.” Above: A young girl looks at John Brown’s grave in New York. (Library of Congress)

Related topics: African Americans, emancipation