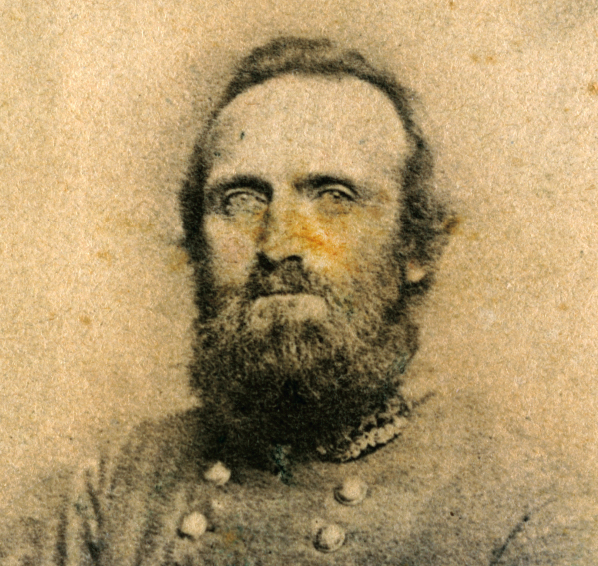

Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, as he appeared in November 1862.

“Oh, for the presence and inspiration of Old Jack for just one hour!”

That was the cry of Lieutenant Colonel Alexander “Sandie” Pendleton, a former staff member of Lieutenant General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, when his new superior, Lieutenant General Richard S. Ewell, decided against attacking Cemetery Hill in the waning hours of the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg. At least, so writes Henry Kyd Douglas, another member of Jackson’s staff, in his influential memoir, I Rode With Stonewall.1

But Pendleton almost certainly did not say these words. A letter by Pendleton, written just after Gettysburg, contains no criticism of Ewell and places responsibility for the defeat with General Robert E. Lee.2

But his supposed sentiment is pervasive. A claim made by the Rev. J. William Jones, who knew Lee after the war, is even more extravagant. In an 1874 memoir he declared that Lee said shortly before his death, “If I had had Stonewall Jackson at Gettysburg, we should have won a great victory. And I feel confident that a complete success there would have resulted in our independence.”3

Historians have marveled at Jackson’s military genius, particularly as displayed in the Shenandoah Valley, at Second Manassas, and during the Chancellorsville Campaign. And frequently in the literature—and certainly in popular imagination—Jackson’s talents seem almost limitless. One of the most powerful components of the American Iliad is Jackson’s power to transform defeat into victory.

Within the psychological framework of Carl Jung, this transformative power corresponds to the “Magician” archetype. “The Magician energy,” write Jungian psychologist Robert Moore and mythologist Douglas Gillette, “is the archetype of awareness and of insight.”4 Jackson was a great warrior, but so were many others. The essence of his genius was the quality of coup d’œil, the ability to take in a situation at a glance and discern what needs to be done. Many writers have claimed that Jackson, had he been at Gettysburg, would have understood that attacking Cemetery Hill was the key to the Union position. Lee is said to have trusted Jackson’s judgment as much as his own, so much so that (again, according to Jones) when he heard firing in the opening phase of the Chancellorsville Campaign, Lee did not concern himself with its significance. Instead he told his staff: “Say to General Jackson that he knows just as well what to do with the enemy as I do.”5

Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson monitors the fighting at First Bull Run in this chromolithograph by H.A. Ogden.

An obvious allusion to Jackson as Magician is his insistence on secrecy. “Mystery—mystery is the secret of success,” is one remark famously attributed to him.6 “If my coat knew my plans, I would burn it at once” is another, referring to his propensity for hiding his intentions even from his staff and subordinates, on the theory that if he could keep secrets from them, he could surely hide them from the enemy.7

His penchant for mystery could elide into eccentricity. Ewell, a division commander under Jackson, once told a colonel that he was certain “Old Jack” was crazy. “He is as mad as a March hare; here he has gone off, I don’t know where, and left me here with no instructions except to watch [Union major general Nathaniel] Banks, and wait until he returns, and when that will be I have not the most remote idea.”8 The Magician archetype helps to explain why the Jackson legend contains numerous expressions of his peculiarities. Many of these would be the portrait of a crackpot if applied to anyone else, but they are beloved elements of the Jackson myth because they underscore his remove from ordinary mortals.

Ewell was the source for many well-known claims about Jackson’s quirks. He insisted that he never saw one of Jackson’s couriers approach without expecting an order to charge the North Pole, and that Jackson said that he never used pepper because it made his left leg weak.9 But tales of Jackson’s odd behavior come from others, too. Lieutenant General Richard Taylor insisted that Jackson habitually sucked lemons: “Where Jackson got his lemons ‘no fellow could find out,’ but he was rarely without one.”10 Henry Kyd Douglas claimed that at the Battle of Gaines’ Mill, Jackson sucked on a lemon throughout the engagement and that it scarcely left his lips “except to be used as a baton to emphasize an order.” At the end of the fight, when Douglas last saw the lemon, “it was torn open and exhausted and thrown away, but the day was over and the battle was won.”11 The infatuation with lemons is such a familiar element of the Jackson legend that one feels a pang of disappointment to find that it is wholly without foundation. Jackson just happened to like fresh fruit.12

Surgeon Daniel B. Conrad of the Stonewall Brigade claimed that Jackson “imagined that the halves of his body did not work and act in accord.”13 West Point classmate Dabney H. Maury said something similar, reporting that Jackson confided to fellow cadets that he had “a peculiar malady which troubled him, and complained that one arm and one leg were heavier than the other, and would occasionally raise his arm straight up, as he said, to let the blood run back into his body, and so relieve the excessive weight.” But Maury added perceptively, “These peculiarities have often been regarded and cited as evidences of the great genius he possessed.”14

Generals Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson confer on the evening of May 1, 1863—the day before Jackson was wounded at Chancellorsville—in this painting by Everett B. D. Julio.

Alongside mystery and eccentricity was a third element: Jackson’s religious faith. This too could be caricatured. Surgeon Conrad merged Jackson’s foibles and religiosity in a single sentence: “He followed hydropathy for dyspepsia, and after a pack in wet sheets every Sunday morning he then attended the Presbyterian church, leading the choir, and the prayer-meetings every night during the week.”15 On one occasion, when two of Jackson’s division commanders made a tactical suggestion, Jackson requested that they wait until morning for his answer. When they left him, one of them—inevitably, it was Ewell—told the other: “Do you know why General Jackson would not decide upon our suggestion at once? It was because he was going to pray over it, before he makes up his mind.” And sure enough, when Ewell returned to Jackson’s headquarters to retrieve a forgotten sword, he found Jackson upon his knees in prayer.

If the story ended there it would sound like another of Jackson’s peculiarities, but the man who told it saw it differently, saying that the general was “praying, doubtless, for Omniscient guidance in all his responsible duties, for his men, and for his country.”16 Indeed, Jackson’s religious faith was an integral part of him, as natural to him as breathing, and English clergyman Parkes Cadman accurately connected it to the Magician archetype, which is also characterized by access to the divine. Cadman spoke of Jackson’s “alliance with eternal realities,” calling him “a spiritual prince who was greater than anything he did.”17

In cold reality there were limits to Jackson’s generalship. He could and did perform poorly—Mark Boatner’s Civil War Dictionary includes an entry for “Jackson of the Chickahominy,” which it calls “A phrase used to distinguish the brilliant ‘Jackson of the Valley’ from the ineffective Stonewall Jackson who failed five times during the Seven Days’ Battles.”18 And a number of military historians believe that Ewell was correct to not attack Cemetery Hill, that with two divisions exhausted from a forced march and extended combat, he could not have stormed an elevation held by ample fresh troops and artillery. By extension, neither could Jackson. But in the American Iliad, Jackson will always be the Magician who could have sent his soldiers whooping the Rebel yell up the slopes of Cemetery Hill, transformed the outcome at Gettysburg, and perhaps even carried the Confederacy to independence.

Mark Grimsley, a history professor at The Ohio State University, is the author of several books, including And Keep Moving On: The Virginia Campaign, May–June 1864 (2002) and The Hard Hand of War: Union Military Policy Toward Southern Civilians, 1861–1865 (1995). He has also written more than 50 articles and essays.

This article appeared in the Fall 2018 issue of The Civil War Monitor.

1. Henry Kyd Douglas, I Rode With Stonewall: The War Experiences of the Youngest Member of Jackson’s Staff (Chapel Hill, 1940), 247. Throughout this column I have cited the earliest printed primary source I can locate, but most are endlessly detailed in the secondary literature.

2. Peter S. Carmichael, “‘Oh, For the Presence and Inspiration of Old Jack’: A Lost Cause Plea for Stonewall Jackson at Gettysburg,” Civil War History 41:2 (June 1995): 163.

3. J. William Jones, Personal Reminiscences, Anecdotes, and Letters of Gen. Robert E. Lee (New York, 1874), 156.

4. Robert Moore and Douglas Gillette, King, Warrior, Magician, Lover: Rediscovering the Archetypes of the Mature Masculine (San Francisco, 1990), 106.

5. Jones, Personal Reminiscences, 155–156.

6. John Esten Cooke, The Life of Stonewall Jackson

(New York, 1863), 85.

7. J. William Jones, “The Career of Stonewall Jackson,” Southern Historical Society Papers, vol. 35 (1907): 83.

8. Ibid.

9. Richard Taylor, Destruction and Reconstruction (New York, 1879), 38.

10. Ibid., 50.

11. Douglas, I Rode With Stonewall, 103–104.

12. James I. Robertson Jr., Stonewall Jackson: The Man, The Soldier, The Legend (New York, 1997), xi.

13. D.B. Conrad, “History of the First Battle of Manassas and the Organization of the Stonewall Brigade,” Southern Historical Society Papers, vol. 19 (1891): 83.

14. Dabney H. Maury, “General T. J. ‘Stonewall’ Jackson: Incidents in the Remarkable Career of the Great Soldier,” Southern Historical Society Papers, vol. 25 (1897): 316.

15. Conrad, “History of the First Battle of Manassas,” 83.

16. R.L. Dabney, Life and Campaigns of Lieut.-General Thomas J. Jackson (New York, 1866), 440.

17. S. Parkes Cadman, “English Clergyman on Stonewall Jackson,” Confederate Veteran, vol. 20 (1912): 220.

18. Mark Mayo Boatner III, The Civil War Dictionary (revised edition; New York, 1991), 433.