Between 1861 and 1865, roughly one thousand photographers captured the people and places of the Civil War; dozens followed the armies, shooting pictures of the men who were firing the guns. “America swarms with the members of the mighty tribe of cameristas,” reported The Times of London in August 1862. “In every glade and by the roadsides of the camp may be seen all kinds of covered carts and portable sheds for the worker in metal acid and sun-ray.”

For the millions of young men so far away from home, having a picture taken was a way to commemorate their service or send a likeness home to loved ones. Soldiers and sailors chose their poses carefully, knowing that their portraits would be a legacy that might outlive them. Yet some photographers did not oblige their customers. One sailor from the USS Monitor complained to his wife after a photographer would not permit him to choose his own pose. “I wanted to select my own attitude and put on spectacle frames,” he wrote in frustration, “but the artist said it was unnecessary. I am sorry now that I did not insist on having my own way.”

Rarely do historians or students of Civil War photography get to glimpse into the photographer’s wartime studio. In most cases, the photographs themselves are the only surviving evidence of what transpired in front of the camera lens. A few trial transcripts survive in the court-martial records at the National Archives, however, that reveal a different sort of backdrop to the photographers’ work during the Civil War.

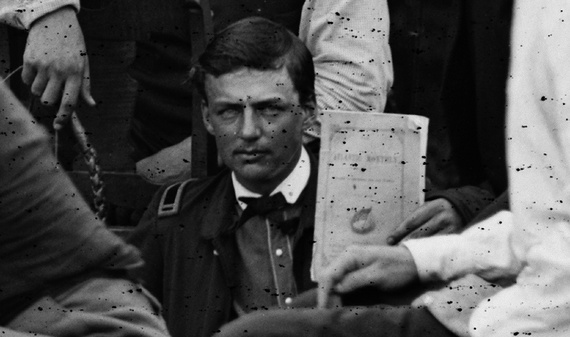

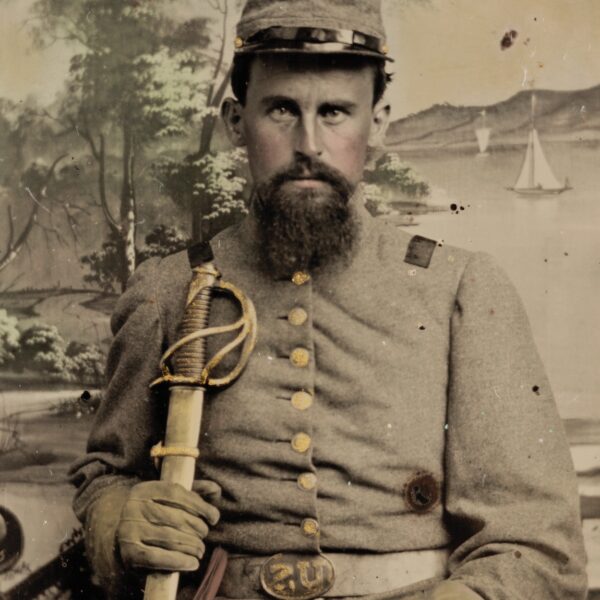

One instance involved the famous Confederate officer Henry Kyd Douglas. Following Robert E. Lee’s surrender on April 9, 1865, Douglas traveled home toward western Maryland, stopping to have his photograph taken in Shepherdstown, West Virginia. An unknown woman accompanied Douglas to the studio and “suggested” that he have his picture taken in his Confederate uniform, which violated the terms of his parole. Douglas gladly complied with the woman’s request, proud to show off his uniform with a major’s star on the collar.

After the session, Douglas noticed that the gallery had become crowded by “quite a number of Ladies and little Girls,” and he did not want to change his coat in front of them. Instead, he walked home in his gray Confederate jacket.

Douglas soon found himself under arrest and charged before a military tribunal for treason, violating his parole, and violation of military orders. He was acquitted of the first two charges, but found guilty of third. He spent two months in prison at Fort Delaware for the photograph he had taken in his rebel garb.

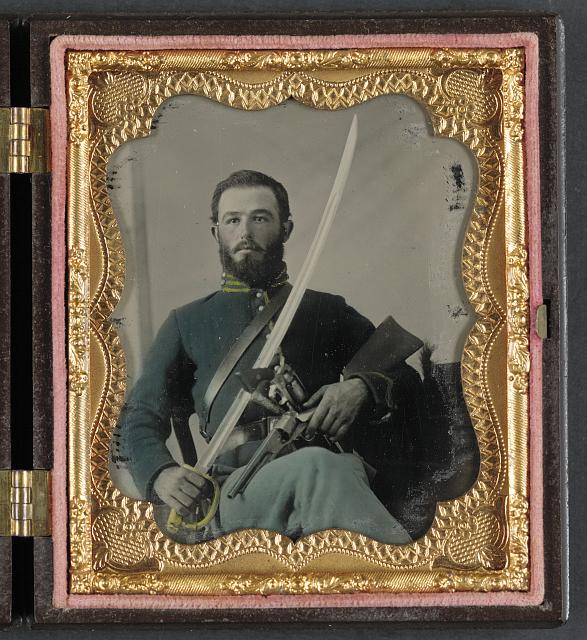

An even more unusual case occurred in the Union army a few years earlier. On August 25, 1862, a twenty-nine-year-old private, Henry J. McCauley of the 11th Pennsylvania Cavalry, joined a group of men who were having their portraits taken at the photography saloon at Camp Hamilton in Hampton, Virginia. The men each sat individually for their pictures as their comrades stood by. McCauley, however, was not a silent bystander. As Private Godfrey Samuel Greenawalt, a soldier in McCauley’s company, sat to have his portrait taken “with arms on,” McCauley remarked that it was “childish” and “folly” to do so. One of those present, Sergeant Joseph Witman, retorted that Greenawalt was entitled to do as he pleased in his own portrait, but the exchange escalated as McCauley continued to offer his opinions. Sergeant Witman finally threatened to slap McCauley if he would not be quiet, at which point McCauley drew his revolver and said he “would shoot any man who came near him.”

McCauley was arrested and court-martialed for “conduct prejudicial to good order and discipline.” The trial took place at Suffolk, Virginia, on October 16 and 17, 1862. According to the specification of the charge, when the officer of the day, Captain E. F. M. Faehtz of the 5th Maryland Volunteers, entered to “quell the disturbance,” McCauley “aimed [his] revolver cocked and loaded” at Captain Faehtz. McCauley pleaded “not guilty” to both the charge and specification.

Testimony at the trial revealed that McCauley did indeed draw his revolver; however, the testimony was inconclusive about whether he actually pointed the firearm at Captain Faehtz. Further, some witnesses suggested that McCauley’s actions resulted from his feeling threatened. Among the most colorful testimony for the defense was that of Private Harry Howser of the 11th Pennsylvania Cavalry. In describing Sergeant Witman’s actions, Howser related, “He told him to shut his mouth or he would make him, the accused asked him how he would make him, he said he would kick his damn’d guts out. The accused then sprang back in the corner as if he were afraid they were all going to attack him, and said now make me shut my chops.”

Captain Robert D. Ward, the commander of McCauley’s company, testified to McCauley’s general obedience and good character, saying that he considered McCauley to be “an excellent soldier.” Despite his tendency to drink “a little too much,” Ward stated that McCauley’s typical behavior was incongruent with this one incident.

The court-martial found McCauley guilty of the specification, but with an exception: It did not find that he had aimed his revolver “cocked and loaded” at the Captain Faehtz. The court thus found no criminality in McCauley’s actions and acquitted him. He would go on to serve for the duration of the war, being wounded on June 29, 1864, at Ream’s Station, and mustering out a year later in June 1865.

If McCauley did in fact point his loaded gun at an officer during a heated debate over whether or not soldiers should pose for pictures with weapons, he certainly missed the irony. Even more importantly, however, moments like these reveal one of the truly unfortunate aspects of Civil War photography. For as common as Civil War photographs are today, the stories behind them are too often lost to history.

Jonathan W. White is an assistant professor of American Studies at Christopher Newport University and the author of Abraham Lincoln and Treason in the Civil War: The Trials of John Merryman (Louisiana State University Press, 2011) and Emancipation, the Union Army, and the Reelection of Abraham Lincoln (Louisiana State University Press, 2014). In 2015 he will publish Lincoln’s Advice to Lawyers with Sourcebooks, and he is presently writing a history of sleep and dreams during the Civil War. To learn more about his research and teaching, please visit http://www.jonathanwhite.org/.

Hailey House will graduate from Christopher Newport University in December 2014 with a degree in American Studies. A native of Richmond, she hopes to work in the public history field after she graduates.

Sources: The pension, military service, and court-martial (KK-461) records of Henry J. McCauley, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.; Samuel P. Bates, History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, 5 vols. (Harrisburg: B. Singerly, 1869-1871); Jeff L. Rosenheim, Photography and the American Civil War (New Haven: Yale University Press for The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013); Jonathan W. White, “A Picture of Treason: The Military Commission Trial of Maj. Henry Kyd Douglas, C.S.A.,” Military Images 32 (Spring 2014), 30-33; Shelby Crouse, “Behind the Iron Shield: William F. Keeler Recalls Life Aboard the Monitor,” forthcoming in Military Images 32 (Fall 2014).

Illustration Courtesy of the Library of Congress (loc.gov).