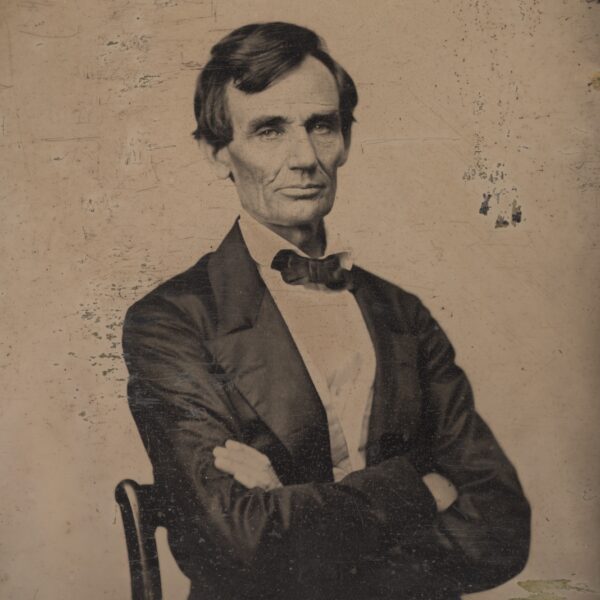

Hunter Davidson understood the Union Navy, having been in Federal service since 1841 as a teen-aged midshipman, a graduate of its Naval Academy and an instructor there, an officer who fought in the War with Mexico and served on the Africa Station, and along the way befriended other talented and daring officers like Robert Minor, and became a protege of Matthew Fontaine Maury, the longtime superintendent of the National Observatory.

When the Civil War broke out, Davidson resigned his commission and his post in Annapolis and became a lieutenant in the Confederate Navy. With Minor and Catesby ap R. Jones, he served as a gunnery officer aboard the ironclad CSS Virginia during the historic battle of Hampton Roads. He became even more well known in the Confederate government when he joined Maury in mining the James River which, coupled with the large guns on Drewry’s Bluff, barred the Union Navy’s advance toward Richmond in the summer of 1862 and throughout the war. When Maury was “exiled” to the Confederate Secret Service in Great Britain in the summer of 1862, Davidson was tapped as his replacement and to head the newly named Submarine Battery Service. He was a firm believer that mines were effective and cheap defenses for the harbors and navigable rivers in the Confederacy. At the time, his work was hailed by Maj. Gen. Robert E. Lee and Flag Officer Franklin Buchanan. The Navy secretary regarded the service “as equal in importance to any division of the army.”

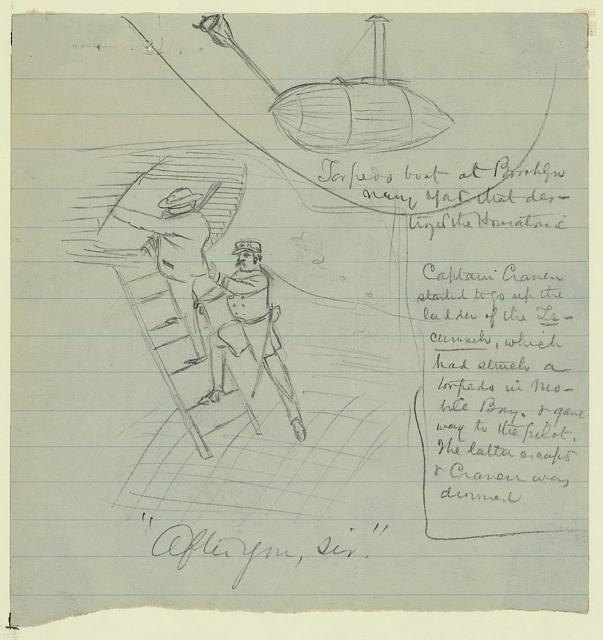

Davidson knew that the service needed specialty vessels — “torpedo boats” — to carry out its existing mission and to take on new ones. These vessels required stealth in design and courage of its operators. He certainly knew about the current work being done in Charleston and other places on submersibles and submarines. He had experience with the spar torpedo fixed on Virginia to be rammed into the wooden hulls of Union warships and was kept abreast of refinements in how to employ it in an attack.

The use of the adjustable spar torpedo had advanced throughout the war. Engineers such as Confederate Army Captain Francis Lee in Charleston worked on making them more flexible to get well under a warship’s waterline and durable enough to endure the collision between the hunter and its prey. The changes were especially noted in operations of submersibles [often called Davids] such as the one piloted by Confederate Navy Lieutenant W.T. Glassell in his attack on the largest Union warship of the time New Ironsides in Charleston’s harbor. These adjustment were also adopted by the constructors of the several times rebuilt submarine H.L. Hunley in its sinking of Housatonic off Charleston.

Eventually, Davidson received four less than 50-foot long Squib class vessels in the James River Squadron. They were cigar-shaped, quiet, maneuverable, and capable of speeds of over 10 knots, considered very good in ramming the explosive home and backing safely away before it detonated. A Union officer wrote admiringly, “the boat had fine lines and would not draw more water than a frigate’s launch.” In short, “it would be very difficult to discern this boat at night at a short distance.” Stealth had been achieved.

By the spring of 1864, the combined Union armies were on the march in Virginia, Tennessee, and Georgia. The blockade was proving ever more effective in slowly starving the Confederacy. The Confederate government was entertaining ever more dangerous ideas on how to stop the onslaught — from raids upon the locks of the Erie Canal to schemes to liberate thousands of prisoners of war being held along the Great Lakes and at Point Lookout on the Maryland shore, where the Potomac enters the Chesapeake Bay.

At this time, Davidson was determined to take it upon himself to finish up what Virginia started two years earlier — sink USS Minnesota, Flag Officer S.P. Lee’s flagship in Hampton Roads. He needed not only the technology of the vessel, its spar torpedo, his own and his seven-man crew’s daring, but also luck for the attack in the early morning of April 9.

About 2 a.m. at ebb tide off Newport News, “a dark object was discovered slowly passing the ship about 200 yards distant.” A lookout on the Union warship shouted to what appeared to be a boat to identify itself. “Roanoke” [a Union ironclad operating in Hampton Roads] came the reply as it kept moving closer. Now the smaller vessel was directly abeam. The officer of the deck shouted to Poppy, a Union tug, to examine the oncoming vessel. But there was no response from the tug to the first command. He kept shouting his orders until finally the men aboard the tug responded, but it did not have enough steam to start moving.

By then what was now identified as a “David” was abaft the port main chains. Although from the Union warship the Confederate vessel appeared to be moving without power, the Squib had enough momentum to ram the spar torpedo with 53 pounds of explosives into Minnesota about 10 feet below the waterline. The explosion sent “the heavy ship rolling to the starboard.” But it did not sink although it had to come off line.

Later inspection confirmed the damage was confined largely to the shell and spirit rooms. The ordnance department reported three 9-inch gun carriages disabled and other damage to equipment, but no further explosion from it damaged the warship.

Backing away, Davidson thought he came under relatively heavy fire, but Squib only had to dodge one round-shot and scattered musket fire. The Union tugs that were to pursue it lost Squib in the darkness as it steamed toward safety in the Nansemond River. Other tugs were to warn the rest of the fleet that an enemy David had attacked Minnesota.

The luck that Davidson needed held.

Lee was furious and recommended Poppy‘s commander be demoted and the acting master’s “mate who was sleeping during his watch be dismissed [from] the service.” He then demanded that all the commanders of steamers ensure that “his tub is kept in a high state of discipline.” As for the tugs, they were to report every half hour from sunset to sunrise to the officers of the deck on the steamers that they were “all ready.”

On the other hand, Davidson proudly reported, “I could not have been associated with braver or better men.”

Long after Appomattox and immensely proud of the attack, he wrote from Paraguay, “This was the only instance during our war, and the first, of course, when the ‘spar torpedo’ was used with effect and without the loss of the attacking party. …On this occasion, the Russian sulphuric acid &c., fuse was used, the same that Captain [W.T.] Glassell used against the ‘Ironsides‘ in Charleston harbor.

Even though Davidson did not succeed in sinking Minnesota, Navy Secretary selected him for promotion to commander for his “cool daring, professional skill, and judgment … in this hazardous enterprise.” His nomination was read in the Confederate Senate the same day that John Kell’s was. Kell had been the long-serving executive officer of commerce raiders Sumter and the far better known Alabama, the legendary scourge of the United States-flagged merchant fleet.

John Grady, a former managing editor of Navy Times and retired communications director of the Association of the United States Army, is completing a biography on Matthew Fontaine Maury. He has contributed to the New York Times “Disunion” series, the Civil War Monitor, and is a blogger for the Navy’s Sesquicentennial of the Civil War site.

Sources: John Coski, Capital Navy: The Men, Ships and Operations of the James River Squadron (Savas Woodbury: Campbell, Calif., 1996); Jefferson Davis and Hunter Davidson, “A Chapter of War History Concerning Torpedoes,” Southern Historical Society Papers, Volume 24; “Hunter Davidson, C.S.N., in Paraguay,” Confederate Veteran, Nashville, Vol. 14, No. 9; John Grady, “Destructionist and Capturer,” Civil War Monitor Front Line blog; Matthew Fontaine Maury Diary, 1864-1865, Maury Papers, Library of Congress; Journals of the Confederate States of America Senate, June 9, 1864, 58th Cong., 2d Sess., Senate Doc. 234, Vol. 4, Feb. 1, 1904, Government Printing Office, Washington; Official Records of Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Ser. 1, Vol. 9; “Squib,” Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, Naval History and Heritage Command.

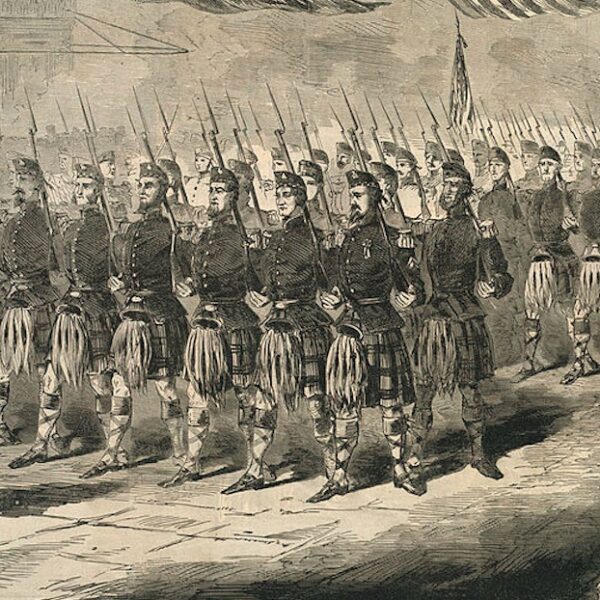

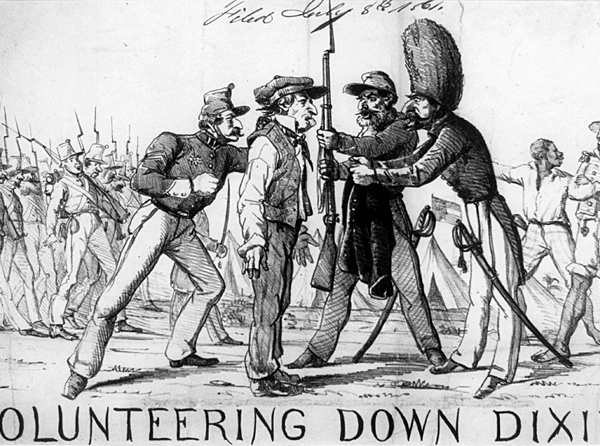

Illustration courtesy Library of Congress (loc.gov).