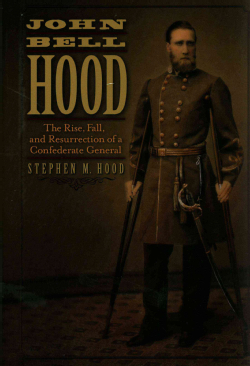

John Bell Hood: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of a Confederate General by Stephen Hood. Savas Beatie, 2013. Cloth, ISBN: 1611211409. $32.95.

If biographers are often guilty of loving their subjects too much, then Stephen M. Hood is innocent. His study of Confederate general John Bell Hood seems to be driven more by the author’s dislike for the historians who have previously written about him than love for his distant cousin. In his effort to resuscitate General Hood’s reputation as a competent if not talented commander who did his best in impossible situations, the author spends far more time and energy skewering those historians than he does giving the reader a new or at least more nuanced interpretation of General Hood. This is a somewhat quixotic mission since Brian Craig Miller’s 2010 book John Bell Hood and the Fight for Civil War Memory has revised many of those older interpretations. The result is a book that is unnecessarily contentious, even shrill at times, because the author is preoccupied with fighting a battle that has, in fact, already been won.

If biographers are often guilty of loving their subjects too much, then Stephen M. Hood is innocent. His study of Confederate general John Bell Hood seems to be driven more by the author’s dislike for the historians who have previously written about him than love for his distant cousin. In his effort to resuscitate General Hood’s reputation as a competent if not talented commander who did his best in impossible situations, the author spends far more time and energy skewering those historians than he does giving the reader a new or at least more nuanced interpretation of General Hood. This is a somewhat quixotic mission since Brian Craig Miller’s 2010 book John Bell Hood and the Fight for Civil War Memory has revised many of those older interpretations. The result is a book that is unnecessarily contentious, even shrill at times, because the author is preoccupied with fighting a battle that has, in fact, already been won.

Historians of the “Lost Cause,” who in their quest to venerate the beloved Robert E. Lee have scapegoated Hood, are squarely within the author’s crosshairs. General Hood, who died too soon to answer the charges of insubordination, butchery, and cowardice that have been heaped upon him, the author argues, was “an idealistic leader who sacrificed half his body attempting (but ultimately failing) to do what was nearly impossible”; that is, save Atlanta and then Tennessee from the invading forces of William Tecumseh Sherman (xxxii). However, the evidence to support this claim resides in what the publisher describes as a “large cache of recently discovered Hood papers,” which are in the author’s possession. Several of these letters are reproduced in the text, but they do little to support the claim that the general was an “idealistic leader.” These letters, written by Hood supporters in the post-war period, are personal recollections that the author believes absolves Hood from blame in the bloody Tennessee Campaign. According to the author, these “eyewitness accounts” are the most reliable forms of evidence an historian can use. To be fair, the author rightly points out how over the years historians have uncritically accepted characterizations of Hood from one another without going back to the primary sources to see if, in fact, those characterizations might have been taken out of context. Unfortunately, this is a common problem in any field of historical inquiry—not just Hood studies. But one would be hard pressed to find an historian working today who would blindly accept a personal recollection as irrefutable fact. These letters, written a decade or more after the war, are compromised by time and perspective. As Carol Reardon points out in her study of Gettysburg, the memory of a battle is being revised even as it is occurring so that just minutes after it is over, one soldier’s recollection may differ considerably from another’s, yet neither is more truthful than the other. William Sherman said as much in the preface to the second edition of his memoir: “any witness who may differ from me should publish his own version of facts in the truthful narration of which he is interested. I am publishing my own memoirs, not theirs, and we all know that no three honest witnesses of a simple brawl can agree on all the details.”1

An intrepid reader may catch glimpses of an interesting, perhaps even admirable, man living with pain of regret and defeat in the pages of this book. It is the ambitious, irascible, sometimes raging military commander who peaks this reader’s interest. Equally compelling is the image of the wounded, laudanum-swilling amputee. Although there may be no evidence to support rumors of alcohol and opium addiction, those rumors might be effectively used as an entry point into a larger discussion about wounded veterans and the struggles they faced after the war was over.2 Instead of trying to portray Hood as a super-man unaffected by physical or emotional pain, why not accept the turmoil that seems to have haunted him both on and off the battlefield? A closer reading of those newly-discovered personal letters might reveal, as Lee’s letters did for Elizabeth Pryor, a man at war with himself as well as with the Union.3 Ironically, in his efforts to prove that John Bell Hood was not the man some historians have made him out to be, the author flattens his personality and motivations, thereby making him a far less interesting man than he might have been.

Even if one does not agree with Ann Douglass’ premise that good biography requires “a love affair, even a marriage, between author and subject,” surely the author must still find something compelling about the subject. Perhaps there is something mysterious or puzzling if not lovable about them?4 Maybe you do not have to love—or even like—your subject, but you have to find them interesting. But there is little of that here. The admiration that the author surely must have for the general is eaten away by the narrative’s corrosive tone. Any sense of who Hood the man was, and not just who he was not, gets lost in the book’s disjointed organization. In short, a reader hoping to get closer to one of the Civil War’s most controversial figures will be disappointed.

Carole Emberton is Associate Professor of History at the University of Buffalo (SUNY). She is the author of Beyond Redemption: Race, Violence, and the American South after the Civil War (2013).

1 Carol Reardon, Pickett’s Charge in History and Memory (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007); William T. Sherman, Memoirs of Gen. William T. Sherman, 2nd Ed. (New York: Appleton & Co., 1889).

2 Brian Craig Miller, John Bell Hood and the Fight for Civil War Memory (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2010): xx.

3 Elizabeth Brown Pryor, Reading the Man: Robert E. Lee through His Private Letters (New York: Viking, 2007).

4 Douglass quoted in Brenda Maddox, “Biography: A Love Affair or a Job?” New York Times Book Review, May 9, 1999. See also Jill Lepore, “Historians Who Love Too Much: Reflections on Microhistory and Biography,” Journal of American History 88, 1 (June 2001): 129-144.