Historian Kevin M. Levin

In November 2005 I created the website Civil War Memory, which included a blog. I had recently completed a master’s degree in history and a thesis on the Battle of the Crater and was looking for ways to connect with people with similar interests. Among a relatively small number of history enthusiasts and academics, blogging was just beginning to gain traction.

Bloggers represented diverse backgrounds and interests. Civil War enthusiasts could pick and choose from sites that focused on individual battles, regiments, and communities to those that addressed controversial questions related to slavery and memory and more. Blog followers included academic historians, students, educators, and readers with a lifelong interest in the war along with those who saw their role as defending their Civil War ancestors. This dynamic often led to lengthy and rich discussions, but it also on occasion descended into insults and threats. The Civil War blogosphere had the potential to educate and infuriate at the same time.

A few blogs from those early years are still producing posts on a fairly regular basis. Al Mackey and Andy Hall continue to share their insights into history and the latest controversies. Andrew Wagenhoffer regularly updates his Civil War Books and Authors with reviews of the latest titles, and Harry Smeltzer continues to update Bull Runnings with new primary sources about the first major land battle of the Civil War. The success and duration of these blogs speaks not just to their authors’ commitments and levels of interest, but also to the usefulness of that now-so-common platform.

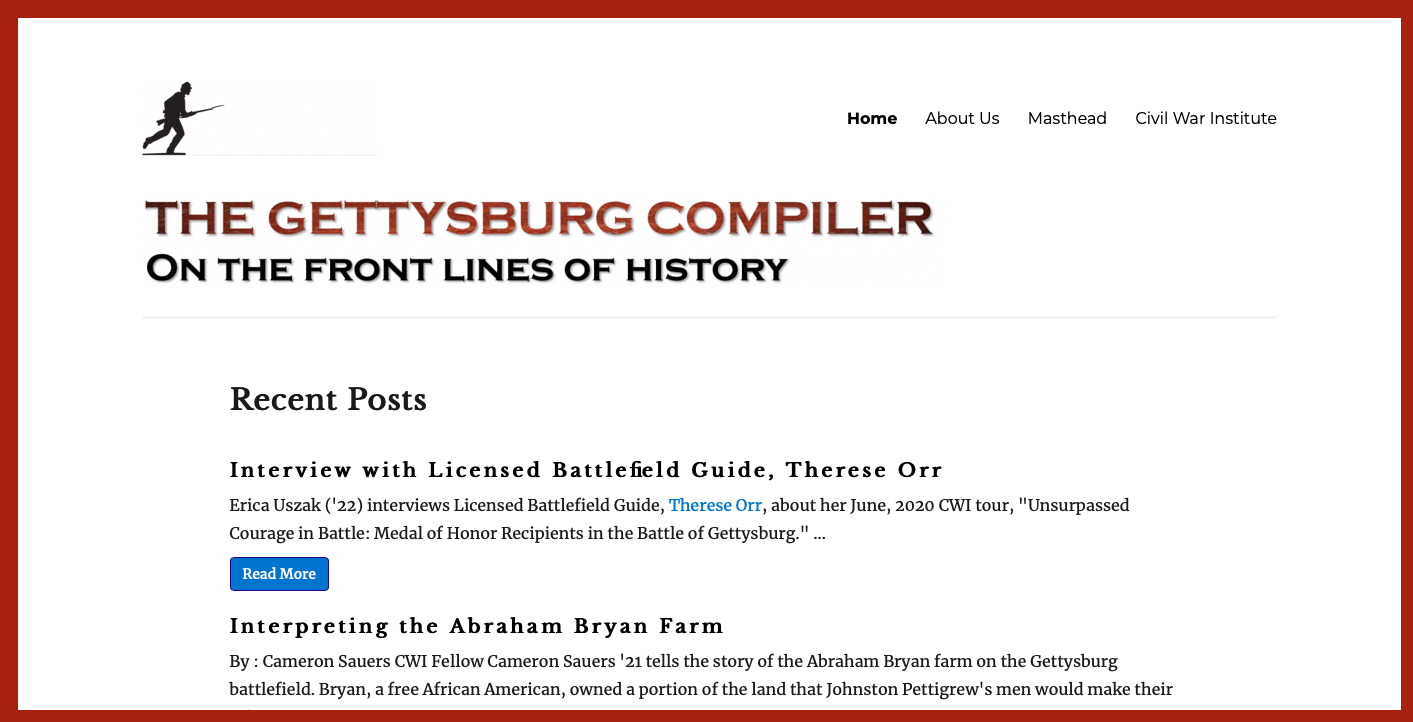

The academic community has always been skeptical about the benefits of blogging and other social media, in part because it distracts from the more traditional forms of publishing such as journal articles and monographs, and in part for its vulnerability to undermining entrenched assumptions about authority and gatekeeping. But that, too, has changed in recent years, due largely to a generation of historians who came of age alongside the rise of social media. The Society of Civil War Historians, which publishes one of two academic journals in the field, maintains a group blog that publishes short essays by a wide range of scholars. Civil Discourse is regularly updated by four young scholars who have either recently graduated or are pursuing a doctorate in history. The Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College’s blog provides a space for students to share their research and learn how to write for a broad audience. These group blogs provide young scholars the opportunity to highlight their research and connect with other scholars as well as the general public.

The most successful group blog may be Emerging Civil War. Founded in 2011, the site hosts numerous academic and nonacademic writers who cover a wide range of Civil War topics. The site’s success has led to an annual conference and two book series (with Savas Beatie Publishing and Southern Illinois University Press) that feature the blog’s writers.

While the number of new individual blogs has declined, one exception is Patrick Young’s The Reconstruction Era. Young’s regularly updated site focuses on the history of the period, including close analysis of primary sources and commentary on important anniversaries related to the sesquicentennial of Reconstruction.

The overall decline of blogging is due, in part, to the rise of what are best described as micro-blogging platforms such as Facebook and Twitter. These platforms offer writers the opportunity to post relatively short pieces with the potential to connect with large audiences. There are literally thousands of examples of how individuals and historical institutions are using Facebook to spread their messages; Garry Adelman’s Civil War Page is one of the most creative. Adelman, the director of education at the American Battlefield Trust, regularly posts close readings of Civil War–era photographs and short videos from battlefields and other historic sites to a community of over 27,000 followers. Facebook works well not just as a platform for featuring photographs and videos, but as a vehicle for Adelman to share his infectious passion and deep knowledge.

Over the past few years Twitter has come to dominate the social media landscape. (My own social media output has shifted to Twitter in recent years to the detriment of my blog.) In contrast to other platforms, Twitter limits posts to 280 characters— but that has not prevented users from finding creative ways to share their interests and scholarship with the public.

Though not a specialist in the Civil War, Princeton historian Kevin M. Kruse has amassed over 370,000 Twitter followers. Kruse shares primary sources related to ongoing and past research projects, but his popularity has been fueled largely by his willingness to push back against misinformation and those who politicize the past. His Twitter threads are a master class in how historians interpret evidence and construct interpretations.

Closer to the Civil War era, Georgetown historian Adam Rothman is using his Twitter feed to share documents related to his course on the history of antebellum slavery, while fellow historians Joanne Freeman, Heather Cox Richardson, and Keisha N. Blain draw important connections between the mid-19th century and the present.

The ongoing controversy about Civil War monuments has given historians such as Karen Cox, Adam Domby, and Hilary Green, among others, the opportunity to share research that has informed and helped to dispel many of the myths surrounding Confederate memory of the war.

A smaller number of historians and enthusiasts are experimenting with podcasts as a way to bring history to the public. Two excellent examples are Keith Harris’ Rogue Historian and Colin Woodward’s American Rambler. Both podcasts provide engaging, entertaining interviews with Civil War historians. Though it stopped production in 2018, the year after it won a Peabody Award, Uncivil explored a wide range of stories about resistance, covert operations, corruption, mutiny, and counterfeiting during the Civil War.

Regardless of the platform, the embrace of social media by an increasing number of academic and nonacademic historians and history enthusiasts has been a welcome development. The introduction of social media has allowed anyone, regardless of education or qualifications, to publish history online. This democratization of history is a welcome development when it has made possible a more open exchange of information. But it has also fueled the spread of misinformation about the conflict. Hundreds of websites now promote myths—of the black Confederate soldier, for example, and countless others—about the Civil War and Reconstruction.

Confronting myths and demonstrating for others how to distinguish between fact and fiction remain the great challenges for all of us who believe in the positive potential of social media.

KEVIN M. LEVIN IS A HISTORIAN AND EDUCATOR BASED IN BOSTON. HE IS THE AUTHOR OF NUMEROUS BOOKS AND ARTICLES, INCLUDING SEARCHING FOR BLACK CONFEDERATES: THE CIVIL WAR’S MOST PERSISTENT MYTH. YOU CAN FIND HIM ONLINE AT HIS WEBSITE AND ON TWITTER.

This article appeared in the Spring 2020 (Vol. 10, No. 1) issue of The Civil War Monitor.