Harriet Tubman, as she appeared in the late 1860s

Anyone who has spent considerable time in research libraries or logging onto digital archives knows what it feels like to come to the end of an evidentiary road. A promising file of letters reveals huge gaps in the writers’ correspondence. A tantalizing detail in a census record leads nowhere. A diary entry ends with a page torn out. Historians must make what they can of such incomplete evidence and try to reconstruct the past through its fragments. This is why, as the historian Eric Foner put it, “works of history are first and foremost acts of the imagination.”(1)

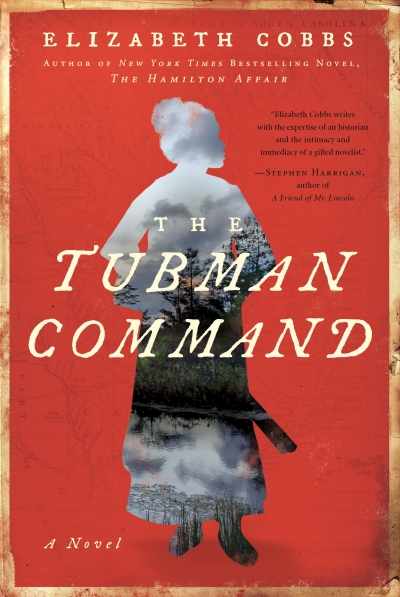

In the author’s note to her new novel, The Tubman Command, Elizabeth Cobbs acknowledges this fact. “Fiction,” she says, “lights the dark corners of evidence.”(2) Cobbs, a professor of American history at Texas A&M University, began writing fiction in 2003. “I wanted to write something that would reach a more general audience,” she told me, “especially readers who didn’t normally go for academic nonfiction.” Her goal, she added, “was to pen something my mother would love.” In her novels, Cobbs uses her imagination and the “tools of history” to understand the lives of those who have shaped the past.

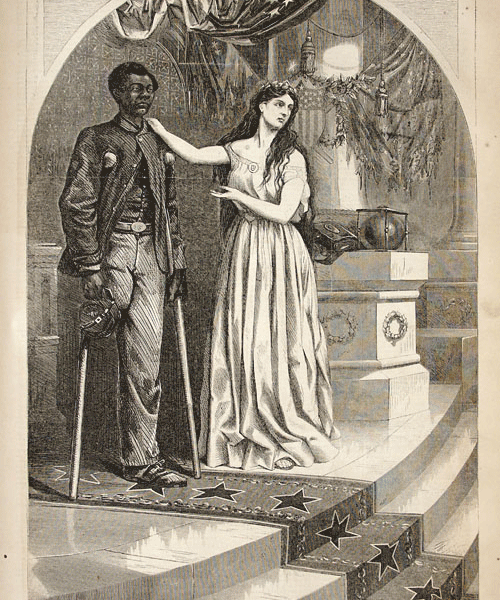

Cobbs’ subject in this novel is Harriet Tubman, whom Americans know as the most recognizable conductor of the Underground Railroad. A runaway herself, Tubman risked her liberty by plunging back into the swamps and forests of the South to help ferry more than 100 enslaved people to freedom in the 1850s. The Tubman Command, however, focuses on her work as a Union spy in Port Royal and Beaufort, South Carolina, in 1863.

That summer, Tubman formulated a plan to sail up the Combahee River, destroy several rice plantations along its banks, and liberate the enslaved women and men laboring there. With a team of male scouts, she identified the locations where Confederates had sunk mines in the river and spread the word among the plantations so that women, men, and children would be ready to move once the Union boats appeared at the plantation docks. And she was on the boats during the attack, helping wherever she was needed. It was due to Tubman’s foresight, energy, and leadership that Union soldiers were able to free more than 750 men, women, and children during the Combahee River Raid. It was the largest liberation of enslaved people in American history.

Author and historian Elizabeth Cobbs

Historians have documented Tubman’s role as the mastermind of the raid, as well as her work as a baker, nurse, and advisor to newly freed people in Port Royal. Cobbs has, as she notes, “followed the record as closely as possible while fleshing out bare facts with plausible fictions” regarding Tubman and a host of other “characters”—who were, in fact, real people—in The Tubman Command.(3) She includes quotations from historical documents as chapter epigraphs and inserts brief contextualizing sections in the text that reflect the latest scholarship in the history of the war and emancipation.

The novel also reflects current scholarship by pushing back against the “white savior” trope so common in Civil War popular culture and depicting a wide range of white characters with whom Tubman interacts. Some are casually racist or blatantly hostile toward Tubman and actively work to undermine her position in Port Royal, Beaufort, and the Union army. There are also several northern white men who are Tubman’s advocates—Colonels James Montgomery and Thomas Wentworth Higginson, in particular. These men understand Tubman’s worth as a leader of men and women, and trust her instincts and expertise. But even these progressive characters must sometimes be forced to act on behalf of enslaved people. In the novel, when a feud between commanders threatens to scuttle the Combahee River Raid, Tubman manipulates General David Hunter’s ambitions to get him to do the right thing after she decides that “she didn’t need to convince General Hunter that the plan was foolproof. She just needed to convince the old paymaster that he had one last chance for glory.”(4)

Because The Tubman Command is a novel and not a history book, Cobbs is able to turn from the historical record and create her own version of Harriet Tubman’s private life. Her Tubman is often thirsty and hungry and exhausted, frustrated and angry. She is attracted to one of her scouts, Samuel Heyward, and they have a (fictionalized) sexual relationship that Cobbs imbues with moving honesty. Heyward ultimately chooses to stay with his wife and children, and Tubman’s sense of betrayal almost overwhelms her at a critical point in the raid. Through Cobbs’ evocative descriptions of her protagonist’s inner life and physical reality, the reader comes to understand Harriet Tubman as not just a revered historical figure, an icon to be depicted on the $20 bill (at some point), or the subject of one of the funniest episodes of the Comedy Central show Drunk History to date, but as a human being.

This is one of the benefits of historical fiction: Readers come to know people who lived in the past in a granular way. They are immersed in the protagonists’ lives, and in their worlds. This is why so many were drawn to Civil War history after reading The Killer Angels, Michael Shaara’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel about the Battle of Gettysburg. Perhaps a new generation of readers will become similarly interested in the complexities of the war after reading The Tubman Command.

There has been a lot of talk recently among historians about how to popularize nonfiction history books. Perhaps using the “tools of fiction” would help historians write in more compelling ways. The people who took part in the Civil War were as real as Harriet Tubman was. Why not tell readers what they looked like, where they lived, what they did when they weren’t writing diary entries or giving orders or thinking big thoughts? These are not meaningless details. They are the real stuff of history. And why not think about the arc of a history book as a plot, rather than a collection of thematic chapters?

“Writing novels has improved my dramatic instincts in nonfiction,” Cobbs told me. “There, one must absolutely stick only to known (or newly discovered) facts, but how the story is told makes a big difference.” History—particularly Civil War history—is replete with good stories that have larger meanings. Historians can tell those stories without abandoning the arguments that usually drive nonfiction books. There remain many dark corners in Civil War history, and historians should illuminate them however they can.

Megan Kate Nelson is a write and historian living in Boston. Her book, The Three-Cornered War: The Union, the Confederacy, and Native Peoples in the Fight for the West, will be published by Scribner in February 2020.

This article appeared in the Fall 2019 (Vol. 9, No. 3) issue of The Civil War Monitor.

(1) Jay Parini, “How Historical Fiction Went Highbrow,” The Atlantic (May 2009): theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2009/05/how-historical-fiction-went-highbrow/307378/

(2) Elizabeth Cobbs, The Tubman Command (Arcade, 2019), 320.

(3) Ibid.

(4) Ibid, 138.