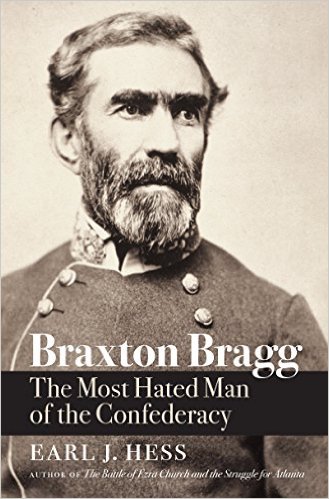

Braxton Bragg: The Most Hated Man of the Confederacy by Earl J. Hess. University of North Carolina Press, 2016. Cloth, ISBN: 978-1-4696-2875-2. $35.00.

A great deal of ink has been spilled over the reputation and generalship of Braxton Bragg, so why do we need another book devoted to this controversial figure? Earl J. Hess suggests that heretofore, no historian has looked at Bragg’s Civil War career objectively. Throughout Braxton Bragg: The Most Hated Man of the Confederacy, he explores the personal relationships and tactical decisions that played a part in creating the Bragg of historical memory. Hess challenges previous scholars by painting a much fairer image of the general. Noting that “historians have tended to see Bragg as the actor in creating a circle of negativity,” Hess illustrates how Bragg “was deeply affected by the actions and opinions of others” (xii).

A great deal of ink has been spilled over the reputation and generalship of Braxton Bragg, so why do we need another book devoted to this controversial figure? Earl J. Hess suggests that heretofore, no historian has looked at Bragg’s Civil War career objectively. Throughout Braxton Bragg: The Most Hated Man of the Confederacy, he explores the personal relationships and tactical decisions that played a part in creating the Bragg of historical memory. Hess challenges previous scholars by painting a much fairer image of the general. Noting that “historians have tended to see Bragg as the actor in creating a circle of negativity,” Hess illustrates how Bragg “was deeply affected by the actions and opinions of others” (xii).

After a brief exploration of Bragg’s pre-war career, Hess arrives at the heart of his analysis of Bragg’s leadership—from his first post at Pensacola to his command of the Army of Tennessee. Hess clearly demonstrates that Bragg preferred to hold as much territory as long as possible, punishing the Union armies he faced while protecting his own as best he could. Unfortunately, this often meant that he needed to make calculated, concentrated attacks against his opponent, despite the fact that he could not trust his subordinate leaders.

Bragg faced stubborn subordinate generals at almost every turn. Perryville, Stones River, Chickamauga, and many smaller engagements all flared up in Bragg’s face when Generals Leonidas Polk, John Breckenridge, Benjamin Cheatham and others failed to carry out their orders—or with the vigor that Bragg required to achieve victory. To Bragg’s discredit, he often responded personally and defensively, driving a wedge between himself and the commanders with whom he disagreed. He preferred demanding that President Jefferson Davis remove subordinates from command or transfer them elsewhere. As the war continued into 1864, many of his officers lost all confidence in him, forcing Davis to replace Bragg with Joseph E. Johnston.

While Bragg failed to encourage a degree of collegiality amongst his officer corps, he certainly faced challenges beyond his control. He faced rumors of his harsh discipline, and the public was swayed by whispers that he wantonly executed Confederate soldiers. Many newspapers became a haven of public protest about Bragg’s leadership, from his perceived discipline of soldiers to his inability to deliver sweeping victories. Hess illustrates that Bragg actually ordered the execution of soldiers at a much lower rate than the national average—and that many of the editorial pieces railing against him stemmed from personal rivalries.

In the end, Hess asserts that Bragg did the best that he could with what he had at his disposal. He argues successfully that no other southern commander could have done better due to the overwhelming territory that Bragg had to defend and the lack of reliable generals under his command. This fact likely inspired Davis to hang onto Bragg’s command for so long, allowing his relationships with his fellow commanders to deteriorate to an irreparable state. All told, Hess calculates, Bragg accounted for 75% of the Army of Tennessee’s tactical successes and 28.5% of its failure days. Contrarily, John Bell Hood, Johnston’s eventual successor singlehandedly accounted for 57.1% of failure days (276).

Hess has offered an enjoyable read that makes a thought-provoking argument. As one would expect, the writing is clear and the photographs are useful in illustrating the subjects throughout the book. If one wants to nitpick, most readers will want more maps to illustrate army maneuvers, especially during the Kentucky Campaign.

All in all, Hess succeeds in arguing in favor of Bragg’s generalship while not discounting his role in the personal conflicts that he endured during the war. He has provided a valuable look at Bragg’s Civil War career and he does an excellent job of including prior scholarship throughout his narrative. Hess consistently examines the events of the war, highlights how the historical record has judged these particular events, and then makes a more objective judgment himself. His even-handed look at Bragg’s military career will be useful reading for anyone interested in Civil War history, particularly the western theater.

Nate Buman received his Ph.D. from Louisiana State University and is currently employed as the Manager of the Shelby County Historical Museum in Harlan, Iowa. He does contract work for the State Historical Society of Iowa and is the former editor of the Civil War Book Review.