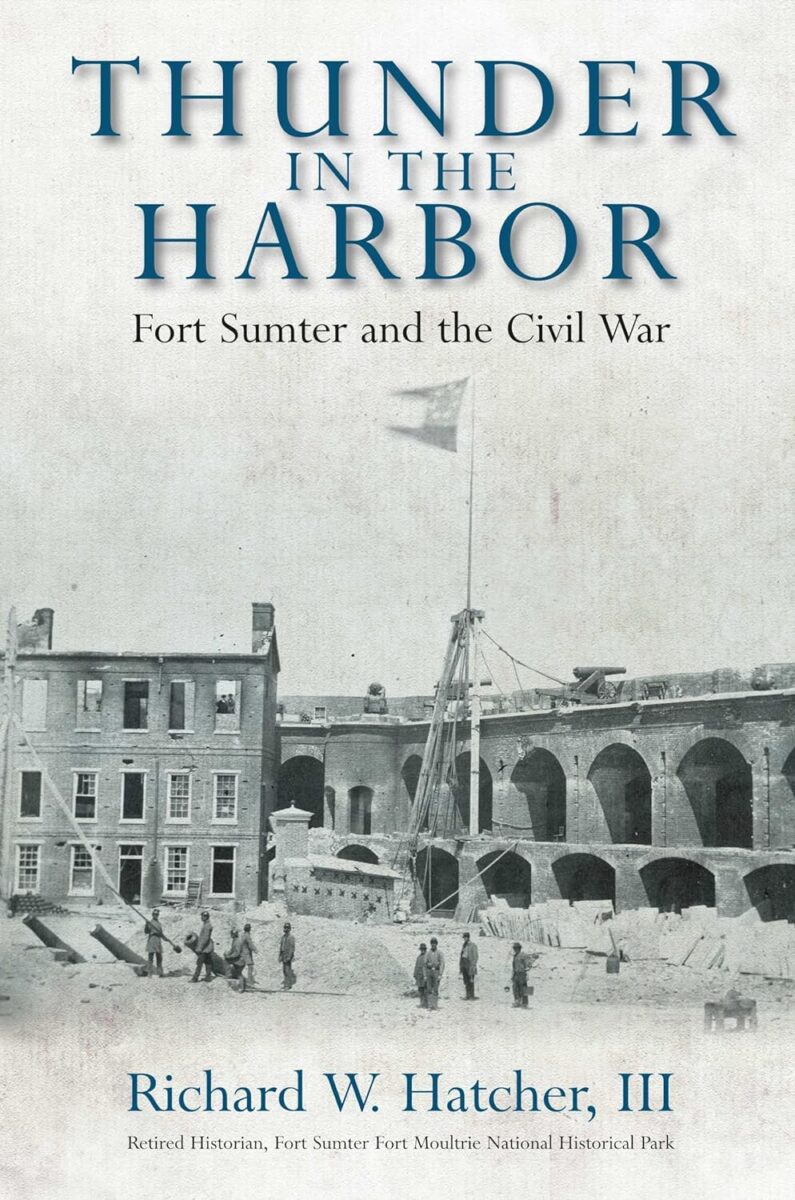

Fort Sumter is likely the most famous of the Civil War era fortresses in the United States. It is a bookend for the bloody four-year crucible of the U.S. Civil War. The mere mention of the site draws instant visuals of the April 12, 1861, bombardment or the April 14, 1865, flag-raising at the end of the conflict. Much of what is known about the fort centers around those two events. Little else has been written about the context in which the fort was proposed, the planning or building of Sumter, or the installation’s post-war years. Richard W. Hatcher III served as the historian at Fort Sumter National Monument and, in his most recent book, Thunder in the Harbor: Fort Sumter and the Civil War, he addresses these holes in the narrative.

Hatcher’s work begins by recounting the origins of the fort and the difficulties encountered in its construction. Approved in 1827 by Secretary of War John C. Calhoun, Fort Sumter’s foundation was not completed for sixteen years. Over that period, the nation crept closer to war as the sectional crisis over slavery and its expansion tested the strength of the Union.

Fort Sumter was still not completed on the eve of the Civil War. Positioned in the mouth of Charleston Harbor, she sat the hotbed of secession. When Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter at 4:30 AM on April 12, 1861, the federal commander, Maj. Robert Anderson, who had led the fort’s garrison through the turbulent winter and spring, refused to abandon his post to the rebels. After a non-stop bombardment, and as his men consumed the last of their rations, Anderson was compelled to surrender the fort.

But what of the events that transpired throughout the next four years of the conflict? Hatcher’s discussion of the Confederate occupation of Fort Sumter and subsequent naval battles and land-based bombardments is unmatched in the historiography.

Considering the many notable figures involved—as well as the longevity of the campaign to recapture the harbor and occupy Charleston—it would be excusable to simply focus on individuals such as P.G.T. Beauregard or record individual unit actions such as the 54th Massachusetts’ assault on Battery Wagner. Hatcher, however, manages to brilliantly locate those well-known individuals and episodes within the larger history of Fort Sumter. By July 1863, Fort Sumter (and other outlying defensive positions such as Fort Moultrie and Battery Gregg and Wagner) had been attacked and severely damaged. Fort Sumter was the target of seemingly daily bombardment. When the embattled fortress was finally captured, its massive masonry walls were in shambles.

On April 14, 1865, Anderson returned to Fort Sumter to raise the same flag he had lowered just four years earlier. To any narrative writer, the symbolism of Anderson’s flag raising would be enough to conclude the story. Hatcher, though, argues that Fort Sumter’s story does not end in 1865. Rather, he chronicles Fort Sumter’s journey from postwar disrepair through its service as a U.S. Armed Forces installation during World War II. Out of the storm of war, Fort Sumter became a national monument—and a place to ponder both the beginning and the end of the U.S. Civil War.

Hatcher’s expertise is apparent and his sifting of source material exhaustive. The author has crafted a detailed and well-plotted history of Fort Sumter and the soldiers, sailors, and civilians, both white and black, who played a role in the events there. Thunder in the Harbor will serve as a seminal work on Fort Sumter for years to come.

Joseph Ricci is a historian at The Battle of Franklin Trust.