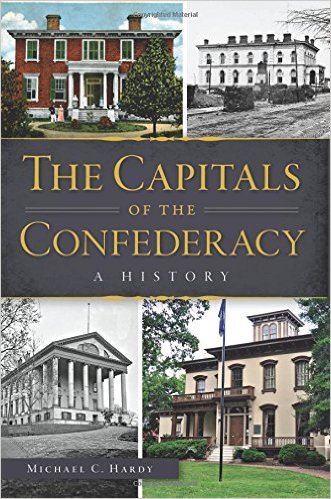

The Capitals of the Confederacy: A History by Michael C. Hardy. Arcadia Publishing, 2015. Paper, ISBN: 978-1626198876. $19.99.

Serving as a nation’s capital city is generally a rare honor—but not in the case of the Confederate States of America, which bestowed it upon five cities in just over four years. It seems almost inexplicable that no single publication considered all of the cities and towns that served as capitals of the Confederacy. Yet this was the case until the publication of Michael C. Hardy’s The Capitals of the Confederacy: A History, which more than capably fills this scholarly void. The period and contemporary photographs prominently featured throughout contribute to its overall value as a handy, all-in-one reference on the Confederate capitals.

Serving as a nation’s capital city is generally a rare honor—but not in the case of the Confederate States of America, which bestowed it upon five cities in just over four years. It seems almost inexplicable that no single publication considered all of the cities and towns that served as capitals of the Confederacy. Yet this was the case until the publication of Michael C. Hardy’s The Capitals of the Confederacy: A History, which more than capably fills this scholarly void. The period and contemporary photographs prominently featured throughout contribute to its overall value as a handy, all-in-one reference on the Confederate capitals.

The book opens with its qualifying criteria for a locale to be labeled a “Confederate capital.” According to Hardy, a site must have been a scene of official government business, such as “meetings of the Confederate cabinet, issuance of official proclamations or other activities of the various branches of its government” (7-8). This definition justifies the inclusion of Greensboro and Charlotte, North Carolina, and further defines the book as a biography of the Confederate government from cradle to grave.

The first six chapters cover the five cities and towns that served as capitals of the Confederacy: (1) Montgomery, Alabama; (2) Richmond, Virginia, which, by virtue of the length of time it served as capital, is divided between two chapters; (3) Danville, Virginia; (4) Greensboro, North Carolina; and (5) Charlotte, North Carolina, where the last cabinet meeting was held, and from which President Jefferson Davis departed on April 26, 1865. Each of these chapters opens with a brief history of that particular locale, from its discovery and founding through the antebellum years, and covers the war years summarily until the dates it served as Confederate capital. The pace then slows considerably as Hardy delves deeper into each site’s experiences.

While strictly speaking beyond the scope of the book, the seventh chapter is devoted to Jefferson Davis’s flight and capture, from April 26 through May 10, 1865. Its inclusion makes logical sense as a continuation and conclusion of the book’s themes, chronicling the final moments of a Confederate government then physically embodied by its president.

The final chapter explores historic sites and markers that one can visit today to commemorate those wartime events in the former capitals, as well as relevant sites relating to the cabinet members’ movements through North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia in 1865. This is a convenient reference for travelers who wish to explore the surviving physical remnants of the Confederate government. For those disinclined to visit themselves, the chapter is still worth reading, as it is liberally sprinkled with the names and addresses of various buildings and monuments, as well as facts relating to the sites and references to structures no longer extant.

Readers are provided with rich details and effective anecdotes, thus evoking a real sense of the people, places, and events in each locale. One of the author’s stated goals is to reveal how the populace of a given capital was affected by the war, and he delivers. Readers are given glimpses into a wide variety of aspects of city life—including economic conditions, social life, medical facilities, public health crises, the impact of nearby battles on the population, and political developments. Utilizing rich quotations from a variety of primary sources, the narrative moves along briskly.

Another of Hardy’s goals is to explore the role of each capital as host to the Confederate cabinet. Thus the reader is presented with a sufficiently detailed yet concise history of how ordinary American cities and towns were, under the stress of fighting a war, transformed into seats of national government. While each capital underwent the same fundamental process—the government moved in, procured living quarters and offices, conducted business, and then packed up and moved out—it played out differently in each locale, varying according to local history and resources and wartime experiences.

Outright comparisons between sites are generally absent, aside from a brief treatment in the introduction and the occasional comment throughout. A more explicit approach would have been unnecessarily heavy-handed, given the readily apparent differences and similarities between the cities and their experiences as Confederate capital.

Some might criticize the volume for its brevity, but this would be both unfair and unfounded. In addition to serving as an excellent introduction to the topic for those unfamiliar with the history or the sources, there is value in examining these locales collectively. In sum, the book stands well as it is, and should remain a reliable reference guide for years to come.

Cathy Wright is the curator of The American Civil War Museum in Richmond.