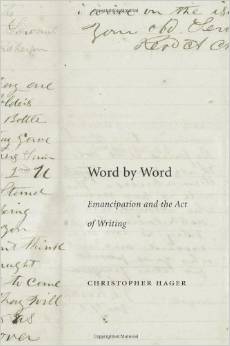

Word By Word: Emancipation and the Act of Writing by Christopher Hager. Harvard University Press, 2013. Cloth, IBSN: 0674059867. $39.95.

In Word by Word, Christopher Hager examines selected antebellum and wartime writings of “marginally literate” slaves and free people of color – that is, people who had gained ability to communicate in written English before emancipation or who were learning to read and write during the Civil War (253, n27). The book “presents an intellectual history of a group that by most accounts had no intellectual history: who were largely illiterate, kept no annals, and whose every move in such directions was brutally suppressed . . . ” (5). Their texts, Hager argues, challenge an ideology of literacy that has linked mastery of writing to the achievement of personal self-determination, economic mobility, and social recognition. In contrast to some abolitionist claims and occasional scholarly readings of the published autobiographical narratives of men and women who successfully escaped slavery, Word by Word proposes that the relationship between literacy and liberation is better viewed as highly contingent, historically specific, and non-systematic rather than absolute. “Nothing intrinsic to the ability to write,” Hager observes, “necessarily shields a person from discipline or repression, and there is little empirical evidence that literacy, if unaccompanied by other advantages, translates into social or economic gain” (17). Everyday uses of literacy by men and women who did not escape slavery do not represent emancipation as a heroic or singularly dramatic individual accomplishment, he finds. Hager therefore depicts writing and emancipation as parallel, provisional processes, both of which emerged from repeated acts of willful perseverance in the face of frequent setbacks. Because “writing encompasses both a submission to norms and the assertion of new meanings,” it “harbors within it a tension between freedom and bondage. It can be freeing, and it can also frustrate and constrain” (21).

In Word by Word, Christopher Hager examines selected antebellum and wartime writings of “marginally literate” slaves and free people of color – that is, people who had gained ability to communicate in written English before emancipation or who were learning to read and write during the Civil War (253, n27). The book “presents an intellectual history of a group that by most accounts had no intellectual history: who were largely illiterate, kept no annals, and whose every move in such directions was brutally suppressed . . . ” (5). Their texts, Hager argues, challenge an ideology of literacy that has linked mastery of writing to the achievement of personal self-determination, economic mobility, and social recognition. In contrast to some abolitionist claims and occasional scholarly readings of the published autobiographical narratives of men and women who successfully escaped slavery, Word by Word proposes that the relationship between literacy and liberation is better viewed as highly contingent, historically specific, and non-systematic rather than absolute. “Nothing intrinsic to the ability to write,” Hager observes, “necessarily shields a person from discipline or repression, and there is little empirical evidence that literacy, if unaccompanied by other advantages, translates into social or economic gain” (17). Everyday uses of literacy by men and women who did not escape slavery do not represent emancipation as a heroic or singularly dramatic individual accomplishment, he finds. Hager therefore depicts writing and emancipation as parallel, provisional processes, both of which emerged from repeated acts of willful perseverance in the face of frequent setbacks. Because “writing encompasses both a submission to norms and the assertion of new meanings,” it “harbors within it a tension between freedom and bondage. It can be freeing, and it can also frustrate and constrain” (21).

Hager explores these frustrations and constraints of slavery and wartime emancipations in closely analyzed, comparative interpretations of texts that were written between 1850 and 1869 by a core group of approximately twenty men and women who lived as literate slaves or who learned to write only as a result of organized wartime instruction. Hager’s selections include texts whose form might well have precluded their consideration in more conventional literary anthologies. Because he regards texts as both intellectual as well as material artifacts, the physical appearance of these writings – changes in ink or in script and the implications of markings and figures, no less than ideas themselves – are analyzed as components of written expression. More conventionally, perhaps, chapters analyze a single text of group of texts, adopting an approach to intellectual history that at times emphasizes textual interpretation and the point of view of a single author over examination of how ideas gain social significance. The selection of texts and authors include a manuscript written by a New Orleans slave worker, known only as “A Colored Man,” who intersperses political commentary among his copybook-like transcriptions of federal wartime policies; the “single surviving letter” to her husband by Maria Perkins, written as she faced imminent sale; autobiographical writings of John M. Washington, which he first wrote while a slave and subsequently revised after his emancipation; “the only surviving diary by . . . newly self-emancipated African American” Union soldier William B. Gould; petitions of protest and grievance written by slave-born South Carolina minister Albert Murcherson and Missouri slave petitioner Martha Glover; and the official reports and manuscript and published letters of slave-born army chaplain Garland H. White. The process of writing such varied texts, Hager argues, reflects the authors’ varying but always desperate encounters with the racial politics of slavery, the ambiguities of wartime emancipation, and an ongoing struggle to master the requirements of a still novel written mode of expression.

Scholars are likely to find some of these writers and texts familiar. But Hager’s concept of “marginal literacy” opens promising ways of re-thinking what we mean by intellectual history and ways of examining the intersections between oral and written domains of expression.

A preoccupation with kin and family that Hager finds to be central to slaves’ antebellum writings intensifies in wartime and post-emancipation petitions to military and civilian officials which, he argues, were written largely by ex-slave men rather than women. Their petitions often addressed some of the distinctive wartime hardships imposed on ex-slave women – either by ideologies of female dependency that excluded them from Union military lines, or by women’s vulnerability to assault by masters outraged at the Union army’s enlistments of slave men. Efforts to write about sexual violence, Hager observes, introduced visible signs of tension in men’s written reports and petitions, as “the suffering authorities never notice, that usually goes unnamed– must here be written and respected” (175). By contrast, he argues, ex-slave women gave oral testimonies about sexual assault with a directness lacking in the written protests drawn up by their brothers, husbands, fathers, and ministers. “In the testimony [Freedmen’s] bureau agents transcribed,” Hager observes, “these women – either urged on by the agents’ questioning or disinclined themselves to hold anything back – offered up the graphic details that seemed to have no place in writing” (165). Hager’s account raises intriguing questions about the gendering of the terms by which literacy became as integral to former slaves’ visions of freedom as their efforts to locate kin; to reconstitute relations of family, work, community; and to defend women’s right to bodily integrity as basic elements of citizenship.

The slaves’ writings that Hager examines were typically addressed to spouses, to themselves (as diarists), or to northern military or civilian personnel whom they regarded as sympathetic. Their writings probe the power relations of an emerging social order. Unlike the antebellum slaves whose letters to their owners have been analyzed by historian Ben Schiller, these authors were rarely in a position to appropriate the codes of a familiar dominant ideology for purposes of muted critique. Many readers are likely to find Hager’s account stimulating.

Julie Saville is Associate Professor of History at the University of Chicago and author of The Work of Reconstruction (1994).