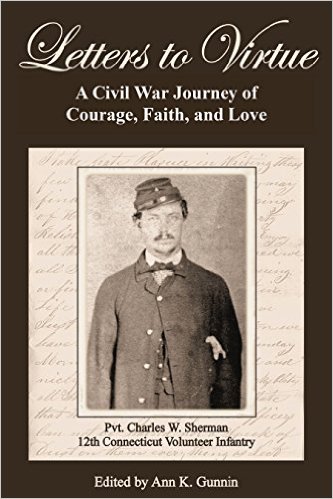

Letters to Virtue: A Civil War Journey of Courage, Faith, and Love—Pvt. Charles W. Sherman, 12th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry edited by Ann K. Gunnin. BookLogix, 2014. Paper, ISBN: 978-1610055208. $29.00.

Situated among the hundreds of headstones in Winchester’s National Cemetery, grave 4053 marks the final resting place of Private Charles W. Sherman, a veteran of the 12th Connecticut Infantry killed at the Battle of Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864. For 150 years after his death, Private Sherman was only a name inscribed on a tombstone—a silent testament to the great sacrifice endured by the Civil War generation. Now, due to a miraculous discovery in a family closet and the efforts of his great-great granddaughter Ann K. Gunnin, Sherman is something more. Through Gunnin’s meticulous efforts to transcribe his letters, his voice is added to the chorus of thousands of Union veterans who can aid Civil War historians in their efforts to understand the many complex facets of the conflict that transformed our country into a nation.

Situated among the hundreds of headstones in Winchester’s National Cemetery, grave 4053 marks the final resting place of Private Charles W. Sherman, a veteran of the 12th Connecticut Infantry killed at the Battle of Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864. For 150 years after his death, Private Sherman was only a name inscribed on a tombstone—a silent testament to the great sacrifice endured by the Civil War generation. Now, due to a miraculous discovery in a family closet and the efforts of his great-great granddaughter Ann K. Gunnin, Sherman is something more. Through Gunnin’s meticulous efforts to transcribe his letters, his voice is added to the chorus of thousands of Union veterans who can aid Civil War historians in their efforts to understand the many complex facets of the conflict that transformed our country into a nation.

After a brief, cogently crafted preface that offers a succinct biographical sketch of Sherman, beginning with his birth in England in 1828 and ending with his death at Cedar Creek in 1864, Gunnin organizes Private Sherman’s 160 letters into twenty chapters. While Gunnin offers brief introductions for each year of the letters and provides explanatory footnotes throughout the book, she does not overburden the text with her commentary, instead allowing Sherman’s thoughts take center stage.

While Sherman’s letters offer insight into a variety of aspects which dominated a soldier’s life and are typical among published collections—weather, a longing for home, the doldrums of camp life, health, mortality, and hatred for the monotony of drill—this assemblage of letters is anything but a typical collection.

Military historians, especially those who study operations in Louisiana or in the Shenandoah Valley, will find Sherman’s descriptions and assessments of engagements such as Port Hudson or the Third Battle of Winchester insightful. Sherman, however, not only offers descriptions of the 12th Connecticut’s movements and roles played on various battlefield, but also provides analyses of his commanders. For example, about three weeks into General Philip H. Sheridan’s tenure as commander of the Army of the Shenandoah, Sherman dubbed “Little Phil” as “the most prudent… of any of our Genrales” (344).

Scholars who study military occupation and the intersections of soldiers and civilians will find significant value in this collection of letters as well. As part of the occupation force of New Orleans in the spring of 1862, Sherman offers praise for General Benjamin F. Butler—not only for the aggressive manner in which he treated ardent Confederate sympathizers, but for how Butler helped alleviate the sufferings of the city’s poorer classes.

Sherman, unsympathetic with Confederate civilians (as he believed they could have done more to “have prevented this War”), also provides examples of how Union soldiers attempted to show their disdain for Confederate civilians. For instance, when troops from General William H. Emory’s Nineteenth Corps, of which the 12th Connecticut was part, passed through Charles Town, West Virginia, in early August 1864, the Union veterans noticed that a substantial number of the townspeople derided the Union soldiers. Incensed by the curses shouted from the civilians, Sherman noted that the 8th Vermont’s regimental band struck up “the Tune of John Browns Souls Marching on” for the “First Famleys of that Place” (335).

Additionally, scholars interested in Union soldiers’ conceptions of honor and manhood will find much material throughout Sherman’s letters to his wife, Virtue. For instance, after his wife registered her concern about Sherman serving in the regiment’s color guard, a position which would undoubtedly increase his chances of being injured, Sherman informed his wife that he could not shirk the responsibility simply because it was dangerous. Sherman equated being in danger to gaining honor, and that if danger was not present, then it would be a task better suited for women. He penned his wife in the spring of 1863: “Well if their no Dainger, their whouled not be any honor and wemon whouled go to war and what kind of a World shouled we have then?” (205).

Perhaps the greatest value of Sherman’s rich letters is what his commentary offers to discussions about slavery, emancipation, and the arming of African Americans. Regarded as the “Horace Greeley” of the 12th Connecticut, Sherman held ardent abolitionist sentiments (217). Always a proponent of emancipating the slaves to support the Union war effort, Sherman’s letters are filled with both his support and criticism of President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. While undoubtedly ecstatic that emancipation would put “a good Springfield Rifle” into the hands of a slave and make him “a free man,” he vehemently disagreed with the selective nature of the Emancipation Proclamation—only freeing slaves areas in rebellion against the government of the United States (314). Sherman believed that all slaves should have been freed immediately to bring about the Confederacy’s annihilation.

The richness and depth of Private Sherman’s letters make this collection, so skillfully edited and appropriately illustrated with maps and photographs, a desirable volume for Civil War historians who desire to understand the conflict’s complex dimensions, soldier life, the horrors of the battlefield, gender, occupation, and emancipation.

Jonathan A. Noyalas is Assistant Professor of History & Director of the Center for Civil War History at Lord Fairfax Community College. His most recent book is Civil War Legacy in the Shenandoah.