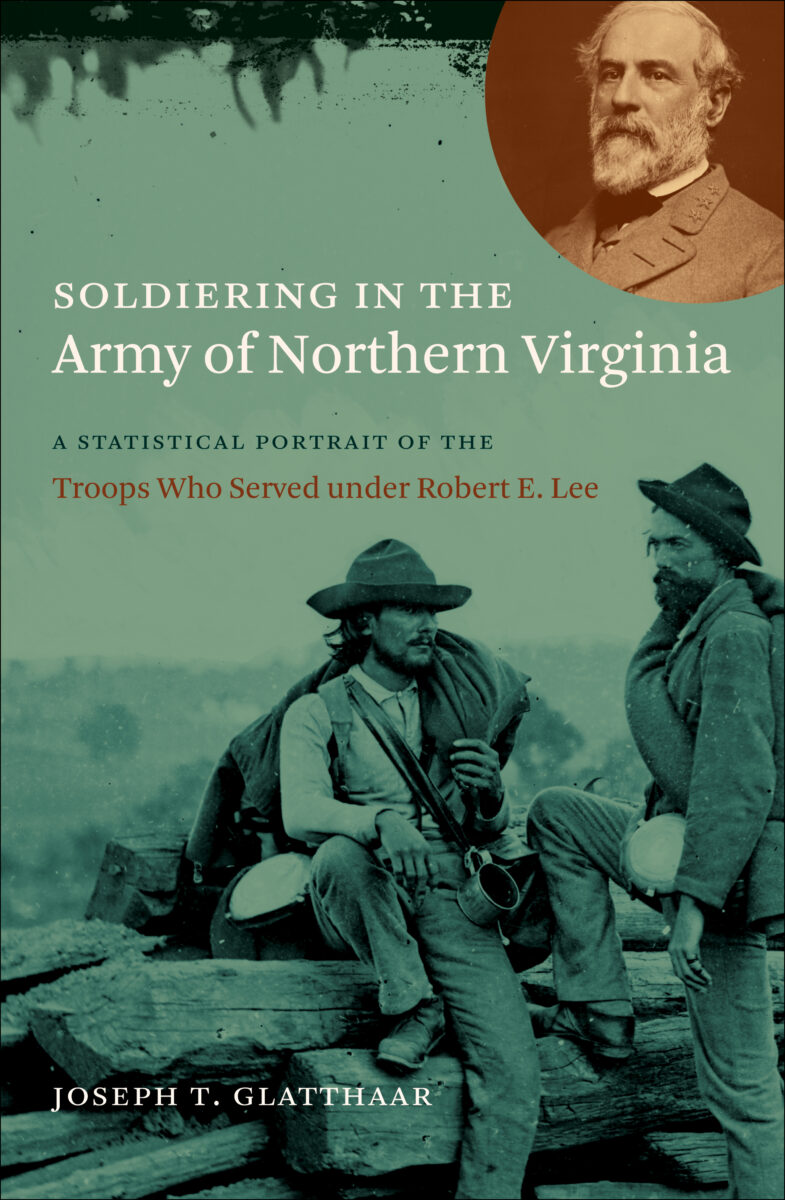

As Joseph Glatthaar argues in his new study, “scholarship that focuses on soldiers is stuck” (xiii). Over the last few years, historians have engaged in a roaring debate about the motivations of the men who marched off to war. Studies have drifted back and forth over the importance of slavery and the concept of Union. Glatthaar notes that historians form an argument and then cherry pick a few letters and diaries to prove their argument and make a sweeping claim that this particular point of view represents a majority of the rank and file soldiers. Thus, statistics that explore the make up of an army may shed new light and end the “logjam” within the realm of common soldier studies, according to the author.

Designed as a companion to his superb 2008 work General Lee’s Army: From Victory to Collapse, the statistical volume breaks down the sample of six hundred soldiers that Glatthaar used to tell the story of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. The sample breaks down to three hundred soldiers in the infantry and one hundred and fifty in each of the cavalry and artillery. Then, impressively, Glatthaar gathered data for each soldier in fifty-four different categories, a painstaking process that took years. No one else in the scope of Civil War scholarship has attempted this comprehensive gathering of statistics about the men who fought in one army. Surely, the discipline will benefit from more studies that take on the other major armies that traipsed across the landscape during the American Civil War.

Most of the chapters follow the same format, as Glatthaar talks about several of the categories through a particular lens. Thankfully, he has included a plethora of graphs that visually explain the statistics examined in each paragraph. For the most part, he focuses on a few particular categories, which includes year of birth, geographic location, occupation, slaveholding, personal and family wealth, year of enlistment, desertion and casualty rates. The categories are then broken down into particular subjects, including the army, the infantry, cavalry and artillery. He also examines northern and foreign-born soldiers, those from the upper and lower south, officers and years of enlistment. The final few chapters re-examine some of the categories, including age, marriage and fatherhood, class and slaveholding status. To his credit, the author also points out the margin of error within many of his statistical examples. After all, the statistical samples only represent six-hundred soldiers and Glatthaar carefully notes that the samples tell us quite a bit about these particular men but are not definitive statements about every single soldier who marched in the ranks under Robert E. Lee.

The statistics provide some revelatory and fascinating insights, especially since the war emerged as “a rich, moderate, and poor man’s fight” (10). A vast majority of the army came from farming communities in the states of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia. The soldiers tended to enlist at a younger age overall, several of them as students, as older soldiers “found the camp hardships, campaigning, and absence from loved ones to be overwhelming” (126). Surprisingly, when you combine personal and family wealth together, several soldiers emerged from wealthy slaveholding families. Traditionally, Lost Cause ideology has strongly asserted that Confederate soldiers fought to protect their homes from bombastic Yankee invaders. However, property records note that over a third of the Army of Northern Virginia had a direct connection to slavery, marking it a “powerful motivation in their military service” (154). Slaveholders in the army also “incurred higher casualties, deserted less frequently, and suffered more for their slaveholding Confederacy” (165). Wealth also ensured a better survival rate, as Glatthaar notes that wealthy soldiers and officers had better access early on to nutrition and supplies to assist in a speedy medical recovery. Still, while a vast majority of men came from poverty, it proves difficult to make a definitive statement that the Civil War attained the status of a “rich man’s war, poor man’s fight,” which has been argued for generations. In terms of desertion, soldiers tended to depart the war when they were in close geographic proximity to their home and when they had “duties to a wife and children at home” that “sometimes trumped military obligations” (139).

I wish Glatthaar had included an appendix with extensive tables that listed his soldiers and some of the major bits of information used in the statistical analysis. Although each chapter begins with a brief vignette about an officer or soldier, the human dimension of war gets lost amongst the steady progression through a wealth of numerical data. Statistics can make for a very slow read, which the author readily admits. Thus, the volume is better suited for researchers or anyone in need of some specific data about the Army of Northern Virginia. Yet, this in no way diminishes the tremendous amount of work the author has put into this conscientious project. Simply put, Glatthaar has constructed a superb resource for anyone interested in expanding their knowledge of one of the most famous armies in Civil War history.

Brian Craig Miller is an Assistant Professor of History and Associate Chair of History at Emporia State University and the author of John Bell Hood and the Fight for Civil War Memory.