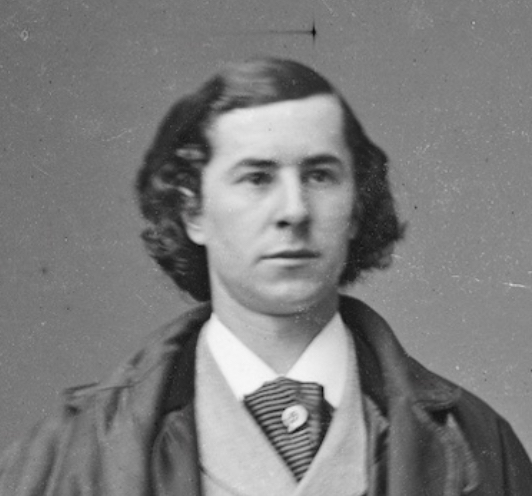

Edwin Forbes is best known today for his work during the Civil War as a special correspondent for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, to which he supplied a multitude of illustrations based upon his first-hand observances while embedded with the Union army. Between 1862 and 1864, Forbes’ skilled hand captured some of the war’s major battles, including Second Manassas, Antietam, Chancellorsville, the Wilderness, and Petersburg. At Gettysburg, Forbes yet again was an eyewitness to history, sketching the epic engagement as it unfolded.

After the war, Forbes continued to produce works based on his wartime experiences, including a series of copper etchings titled “Life Studies of the Great Army,” which garnered significant acclaim upon its release in 1876. (Click here to view a selection of these etchings.) He also created a number of oil paintings, including Civil War scenes. While most of these have not survived, a dozen of these paintings—all pertaining to the Battle of Gettysburg, and presented below—are still extant, preserved today by the Library of Congress.

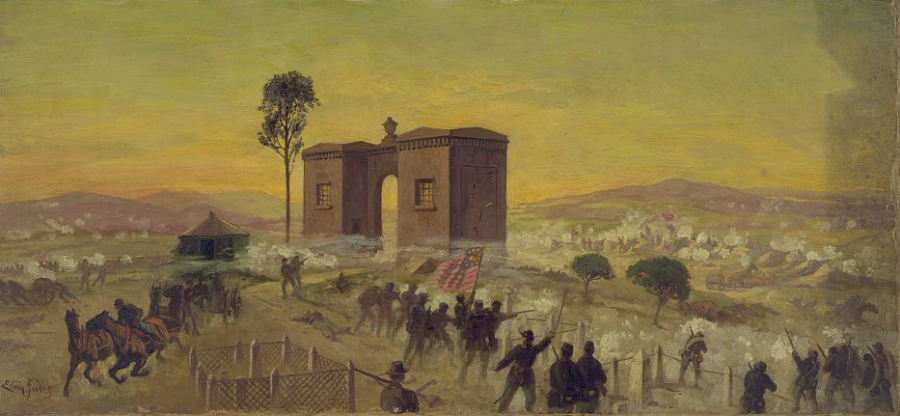

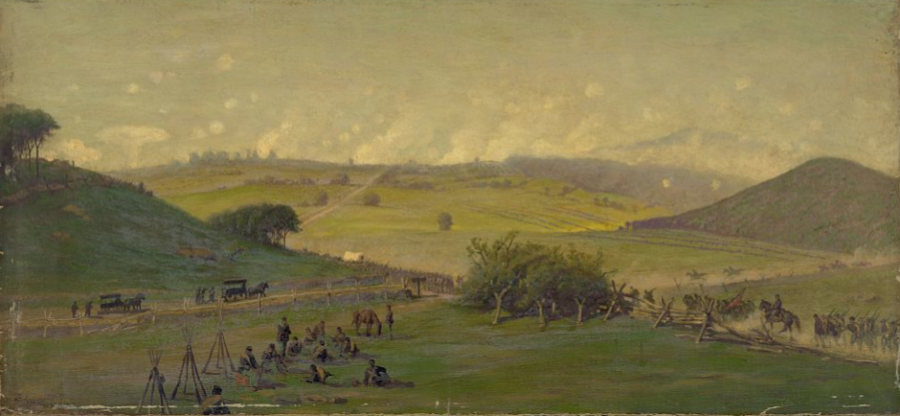

On the battle’s second day, July 2, 1863, Union general Daniel Sickles and his staff (on horseback) inspect the lines of the III Corps on the edge of the Peach Orchard. Confederate forces can be seen massing for an attack in the distance. (Credit for this and all subsequent images: Library of Congress.)

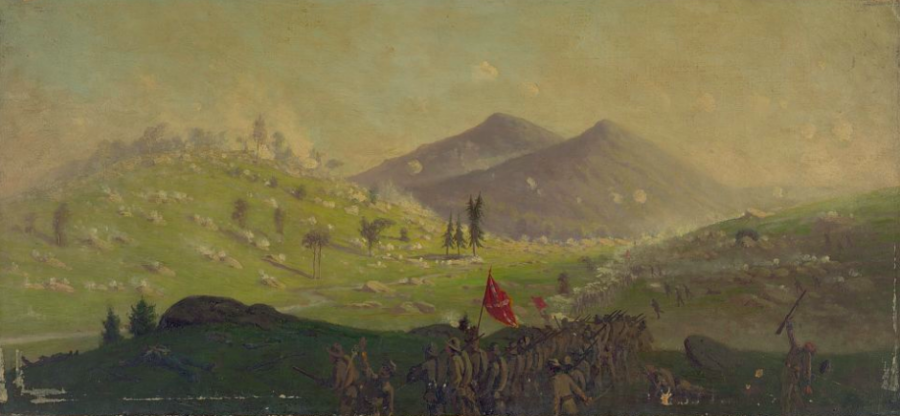

Confederate infantrymen advance upon Union forces positioned along the rocky slope of Little Round Top. Note how Forbes has incorrectly depicted nearby Big Round Top, which he’s shown as having two peaks instead of one.

During the early evening hours of July 2, Confederates from Major General Edward “Allegheny” Johnson’s division move against Union defenses atop Culp’s Hill.

Not long after the attack on Culp’s Hill began, Confederates under the command of Richard S. Ewell launched an assault against the center of the Army of the Potomac’s line at Cemetery Hill. Hand-to-hand fighting ensued along the crest, where Union gunners were overrun by the swarming Rebel attack. Eventually, Union reinforcements helped beat back the threat.

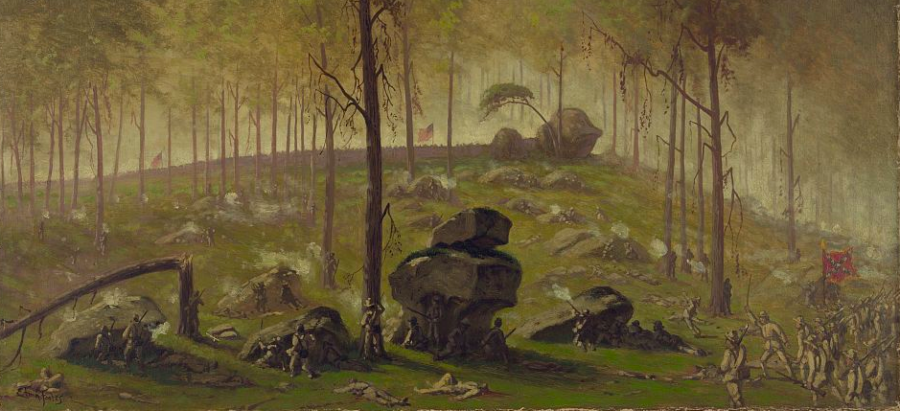

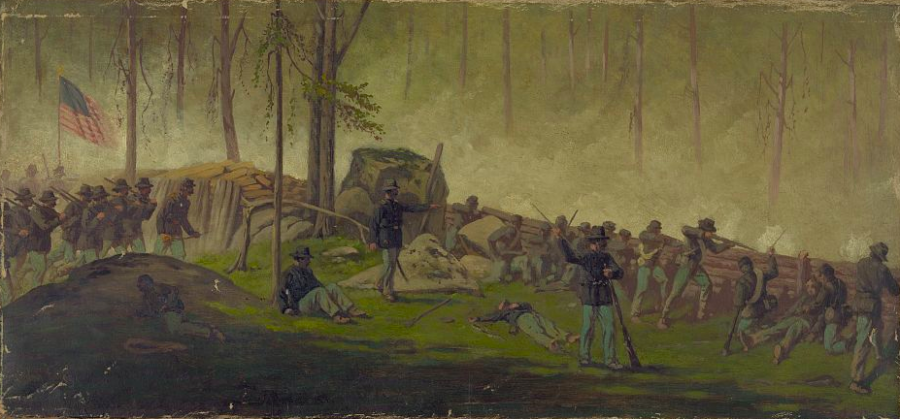

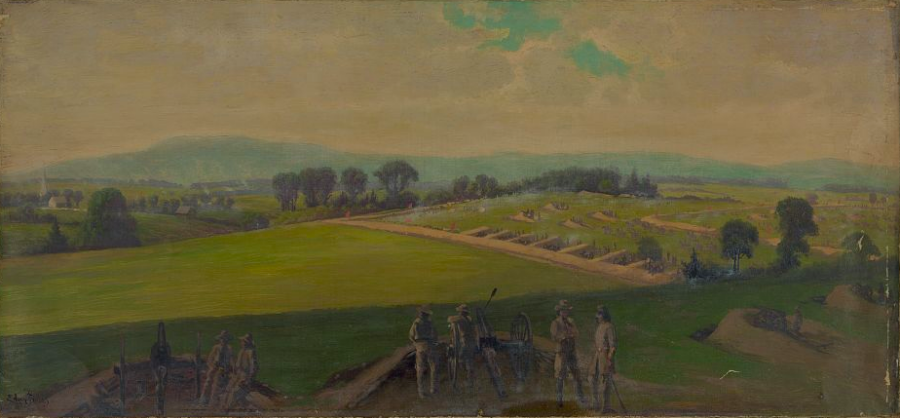

The fight for Culp’s Hill continued into the following day. The hill’s Union defenders, shown here during the morning of July 3, constructed an impressive array of breastworks behind which they fired upon the attacking Confederates.

A general view of Union lines on the morning of July 3, the battle’s final day.

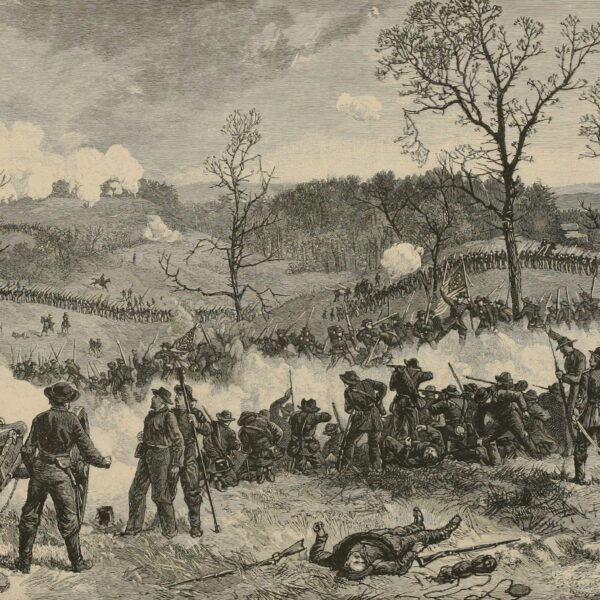

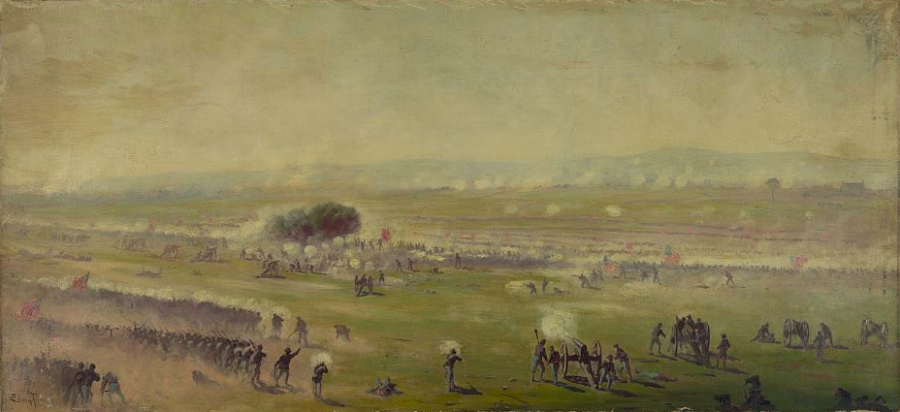

Three Confederate infantry divisions advance upon the center of the Union line during the afternoon of July 3. Known to history as Pickett’s Charge, the Rebel attack proceeded over nearly a mile of open ground before reaching its objective. The famed copse of trees, located at the heart of the Union position, can be seen at right; Ziegler’s Grove is at left.

A closer view of Pickett’s Charge, shown from the Union perspective. Rebels breach the Union line at the copse of trees, pictured at center-left. Their success was short-lived, however, as Union reinforcements helped push the Confederates back. With the charge’s failure, General Robert E. Lee in effect sounded the end of the 3-day battle, opting to begin readying his army for its return to the relative safety of Virginia.

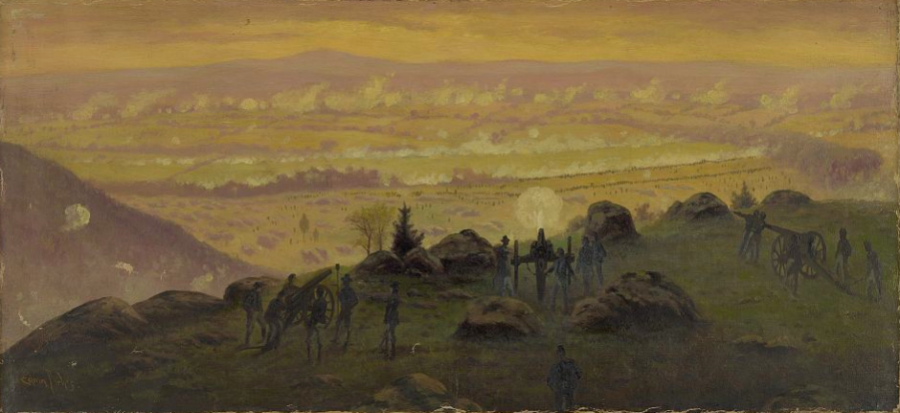

A view from the summit of Little Round Top at 7:30 p.m. on July 3, 1863.

Lee’s Confederates occupy defenses near Hagerstown, Maryland, in the days following the battle in an effort to help protect the retreating Army of Northern Viriginia from approaching Union forces.

Union soldiers pursue Lee’s retreating army in the rain. They men depicted here are on the road near Emmitsburg, Maryland.

The Army of Northern Virginia crosses the Potomac River at Williamsport, Maryland. By July 14, Lee’s army was back in Virginia, having lost over 23,000 men killed, wounded, captured, or missing during the Gettysburg Campaign. The victorious Union Army of the Pototac suffered nearly as many casualties, making the Battle of Gettysburg the Civil War’s bloodiest.