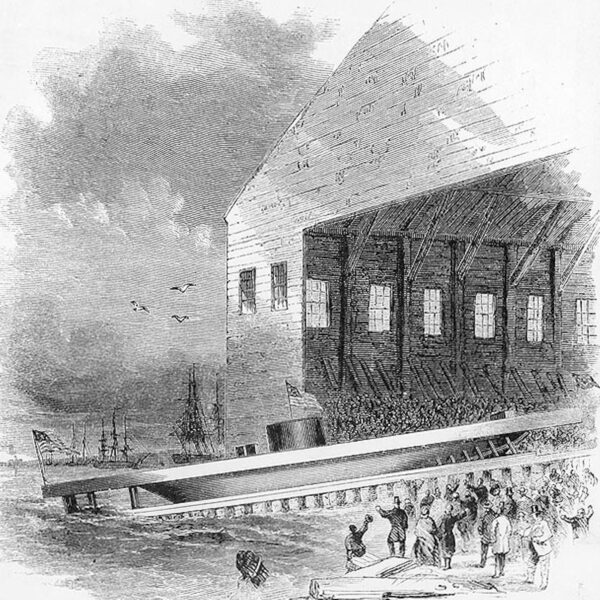

Library of Congress

Library of CongressAppomattox Court House, Virginia, as it appeared in the 1930s.

In May 1932, Mary Davidson Carter, a member of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) from Upperville, Virginia, was angry. She had just learned that the federal government was planning to erect a Peace Monument at the scene of General Robert E. Lee’s surrender to General Ulysses S. Grant on April 9, 1865, in Appomattox Court House, Virginia—a monument that would feature both generals in marble tribute. In a fiery missive to Brigadier General L.H. Bash of the War Department, she criticized the government for undertaking such a project in the midst of the Great Depression and described Appomattox as “the place where Constitutional Government and Lee were crucified in 1865.”Such a monument to “peace and an undivided nation,” she sarcastically quipped, “is an inspiration!” “Please finish it as soon as possible,” she demanded, “so as to get our minds off our present troubles and focused on the Loving-kindness of Lincoln and the Yankees!”1

Unlike Mary Carter, in the decades following Lee’s surrender, Union and Confederate veterans had seen Appomattox as a site of fraternal camaraderie and the immediate dissolution of sectional animosities.In the 1890s, they would jointly endorse proposals for a national park at the site of peace and call for a national memorial. The fierce fight that eruptedbetween the War Department and Confederate groups in the 1930s, however, reflected a significant shift in historical memory. As the aging veterans passed from the scene, a new generation of white southerners led in large part by the UDC began to employ the memory of the Civil War, or more precisely, the memory of Reconstruction, to maintain control of the war’s interpretation. Although most Americans continued to embrace reconciliation in the 1930s, the battle over the Peace Monument reflected a significant departure from the rhetoric of sectional harmony among the most active and vocal Confederate memorialists. Contrary to notions that wounds had healed by 1915, in the 1930s they reopened.

In 1926, a congressional commission recommended the erection of a central Peace Monument and the reconstruction of the dismantled McLean House at Appomattox. Five years later, the War Department invited any American architect of standing and reputation to submit a design for this monument and a landscape treatment of the proposed site. The winning design featured two pylons of either granite or marble banded with laurel at the top and rising from a base symbolizing the nation’s founding. Adorned with the seal of “our undivided nation,” one side of the monument would bear the likeness of Grant while the other of Lee, perhaps with an inscription such as “Duty—the most sublime word in our language.” As the designers explained, the memorial would thus “symbolize an undivided nation and a lasting peace.”2

As word spread that the monument design had been selected. Confederate groups once again rallied around their old flag. Penning a powerful missive to Brig. Gen. L.H. Bash of the War Department, C.A. DeSaussure, Commander-in-Chief of the UCV, warned that the monument would no doubt “foster the very result which their specification endeavors to avoid.” “Who can view this monument without opening afresh the memory of the circumstances which gave rise to its erection, the hot, burning antagonisms, the fierce desire to kill, the death of fathers, husbands, brothers, the privations, the sufferings, the oppressions of those times, the memory of which the 70 years have done so much to obliterate,” he asked. Why not, he asked, “let the dead past bury its dead?” Others pointed to Reconstruction in their opposition. Peter J. White of Richmond believed that Appomattox marked “the advent of the carpetbagger, the scalawag, and a horde of harpies too numerous to mention, the disfranchisement of the whites, the enfranchisement of the blacks, and the horrors of ‘reconstruction.'” “What sort of peace was there after Appomattox?” he asked.3

The most virulent and frequent attacks against the Peace Monument, however, came from the UDC. Like some Confederate men, the UDC employed the rhetoric of Reconstruction to launch their attacks. In an open letter to the Daughters in the fall of 1932, Mary Davidson Carter recommended the women read Claude Bower’s The Tragic Era: The Revolution after Lincoln (1929). In his narrative popular among Confederate groups, he explained how the South had been “placed under Negro and Carpetbag Rule, while Davis, Lee, and all the worth-while were denied the rights of citizenship.” Bower’s work, she said, would remind the UDC of the peril their mothers and grandmothers had faced. Like many white southerners, Carter believed that Reconstruction had been responsible for the rise of the “new negro crime”—black men raping white women.4

It seems hardly coincidental that Carter’s letter describing black men’s uncontrollable desire to rape white women came in the summer and fall of 1932 during the appeals of the so-called Scottsboro boys, nine teenaged African-American boys accused of gang-raping two white women in Alabama. With the case splashed across the nations’ newspapers each day, many white southerners made explicit connections between it and Reconstruction. The New York Times informed its readers that “the memory of the reconstruction period … is a vivid and haunting one” to many in Alabama. Most tellingly, several white women whose names appeared on the affidavit admitted that “they did not care what happened to the Negroes so long as they were killed, because if they were freed the South would not be safe for white women.”5

Consciously or not, Confederate women’s groups made connections between the proposed peace monument and the Scottsboro case. One Richmond, Virginia, association collected clippings about the case in a scrapbook dedicated primarily to Confederate activities. Throughout the summer and fall of 1932, the women attached newspapers articles about the NAACP’s efforts to hinder the Scottsboro case and Alabama “treating its negro population too kindly” next to articles about UDC essay contests and monument dedications. Carter, too, must have been making such connections. Ostensibly talking about Reconstruction, she warned the Daughters that “all over the South white women armed themselves in self-defense.” “The spectacle of negro police leading white girls to jail was not unusual in Montgomery,” she wrote. Clearly women such as Carter envisioned a race war abetted by northern involvement, a second Reconstruction.The Daughters thus harkened back to images of “Yankee aggression,” “black betrayal,” and the alleged rape of white women by black men in Reconstruction to galvanize protest against the Peace Monument. With the Scottsboro trials drawing constant media attention, surely all could see that the consequences of Grant and his Reconstruction policies were still having dire consequences for southern white women.6

This message proved overwhelming successful. Though not all white southerners supported them, by the fall of 1932, UDC chapters and other Confederate women’s organizations from throughout the South had joined the chorus, continuing to flood the War Department with protests. On August 10, 1933, the military parks were transferred, from the War Department to the National Park Service (NPS) in the Department of Interior as part of President Roosevelt’s efforts to reorganize the federal bureaucracy. Two months later, the NPS announced that it had no intention of erecting the peace monument so long as there was any opposition in the South. The park service did not have the inclination to engage in such battles. By February 1934, newspapers were reporting that the monument had been abandoned by the Virginians who had first proposed it. “Old Soldiers Win Fight,” heralded the New York Times, pointing to the “wave of protests from Confederate organizations of women primarily, but backed by a thin gray line,” as the culprit. Attentions now returned to the proposals that had been floated more than forty years earlier to create a battlefield park at the site. On August 13, 1935, President Roosevelt approved the creation of a national historical park at Appomattox with its chief goal the restoration of the McLean House.7

Caroline E. Janney, associate professor of History at Purdue University, has published widely on Civil War memory, including Burying the Dead but Not the Past: Ladies’ Memorial Associations and the Lost Cause and the forthcoming Remembering the Civil War: Reunion and the Limits of Reconciliation.

1 Mary Davidson Carter to Bash, U.S. Quartermaster General, May 2, 1932, Records of the National Park Service, Record Group 79, National Archives, Washington, D.C. For an extended version of this essay, see Caroline E. Janney, “War over the Shrine of Peace: The Appomattox Peace Monument and Retreat from Reconciliation,” Journal of Southern History (vol. 77, no. 1, February 2011): 91-120.

2 Washington Post, Nov. 15, 1931; Copy of Report of the Jury appointed to select design, to the Quartermaster General, March 9, 1932, Records of the Commission of Fine, NARA; Washington Post, March 12, 1932; New York Times, March 12, 1932.

3 C.A. DeSaussure, Commander-in-Chief of the UCV, to Quarter Master General Bash, April 20, 1932, Record Group 79, National Archives.

4 “An Open letter to the Daughters of the Confederacy by Mary D. Carter,” included in Mary D. Carter to Anna Jones, Appomattox UDC, September 21, 1932, Record Group 79, National Archives.

5 F. Raymond Daniell, “Background Study of Scottsboro Case,” New York Times, April 16, 1933.

6 UDC Scrapbook C-9, Museum of the Confederacy, Richmond, Va.; “An Open letter to the Daughters of the Confederacy by Mary D. Carter,” included in Mary D. Carter to Anna Jones, Appomattox UDC, September 21, 1932, Record Group 79, National Archives.

7 Washington Post, Feb. 3, 1934, Sept. 14, 1935; New York Times, March 4, 1934. Emphasis added; RichmondTimes Dispatch, Feb. 3, 1934.

Photo Credit: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs