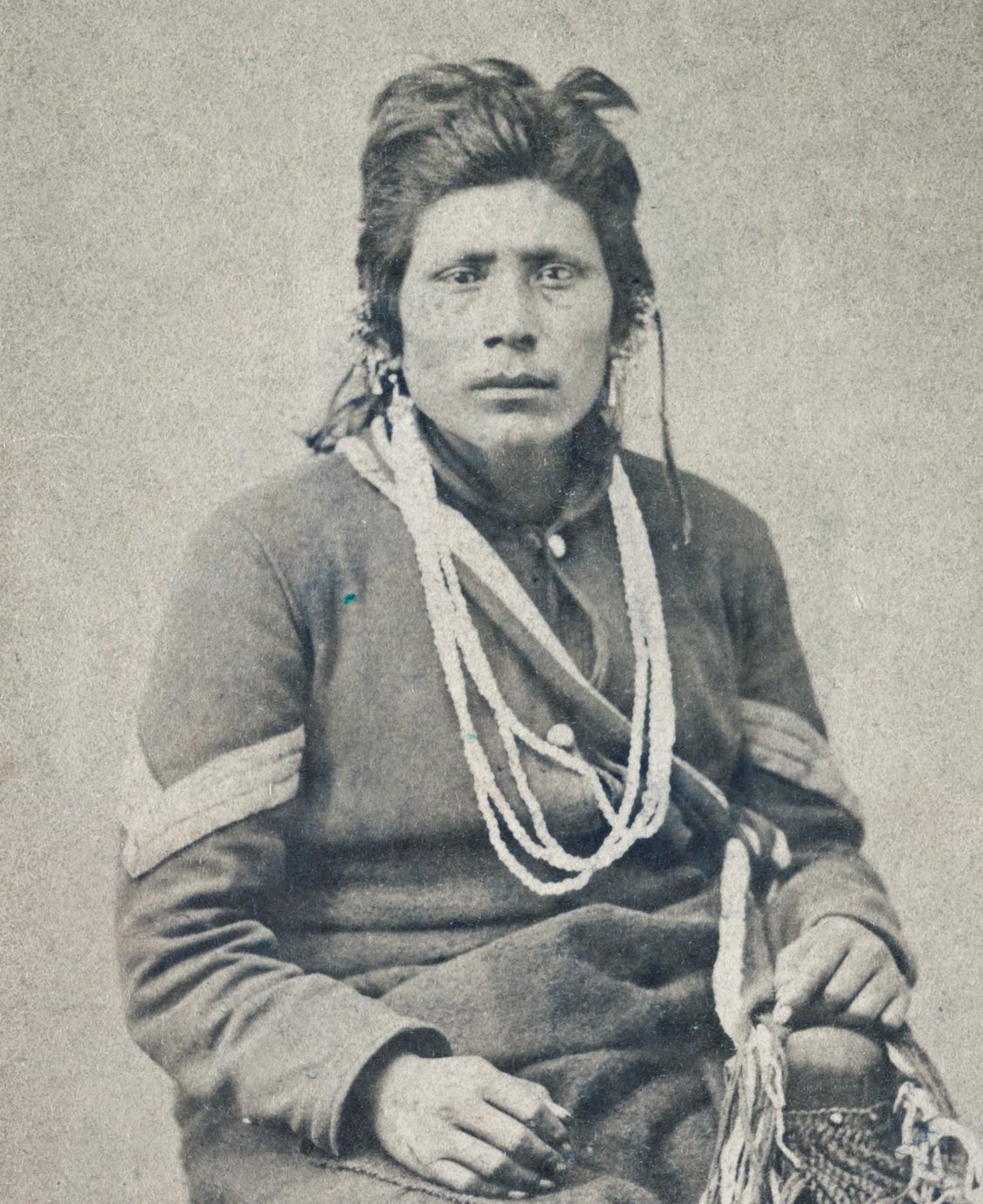

A Native American Union soldier during the Civil War Library of Congress

Library of Congress

On the first day of my American West in History and Film class, I ask students to explain where the historical West of their imaginations is located, when it existed, and what characteristics make it distinctly “western.” As the discussion progresses, it gradually becomes clear that, though each of them assumes their version is the West, we all have different ideas about the American West, be it a geographical place or an imagined one.

It is not much different among historians of the Civil War. For decades, we have been debating where the West begins, what makes it western, and if the answers to those questions actually matter to the bigger story of the conflict or to its outcome. And for just as long we have posed many of the same inconclusive theories.

To many traditional scholars of the Civil War, the West is synonymous with the conflict’s western theater (Georgia, Tennessee, Kentucky, Alabama, Mississippi, as well as parts of Florida and South Carolina), a geographic zone defined by its relative orientation to the primary battlegrounds of the eastern theater (Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and parts of North Carolina). To some historians working on irregular violence and homefront conflicts, entering the West requires a trek into the Appalachian Mountains; to others, it means a trip across the Mississippi River, into the borderlands of Missouri, Arkansas, and Kansas. Still others find the West in a broader Trans-Mississippi theater that includes Texas, Louisiana, and Indian Territory, while another group, exemplified by Matthew Stanley’s The Loyal West (University of Illinois Press, 2017), see the Civil War West in today’s Middle West, a cluster of states encompassing parts of the Ohio Valley and Great Lakes regions.

In the last two decades, and especially in the last few years, there has been a pronounced push among Civil War historians to investigate this historical Far West. (The contemporary definition is the region generally west of the Rocky Mountains.) Their geographic categorization sometimes includes Texas, but often locales even beyond it, such as the Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and Nevada territories, and California. Recent scholarship on the Far West—collectively dubbed “the New Civil War in the West”—prioritizes the interactions and perspectives of people thousands of miles from wartime capitals and high-profile generals or their flagship armies: Native Americans, Mexicans, white settlers on the frontier, military units there, and even foreign governments. Generally, these scholars explore concepts like sovereignty and imperialism; namely, how imperialist visions factored into the wartime and postbellum plans of the United States, the Confederacy, and the people who would presumably be displaced to make those visions a reality.

A selection of standout books covering all these various notions—the western theater, the Middle West, the Trans-Mississippi West, the Mountain West, the Border West, and the Far West—would include a wide range of titles. But because nonacademic readers may be least familiar with the characters and campaigns of the Far West, they were the focus in selecting these five books.

The Civil War in the American West

By Alvin M. Josephy Jr.

(Knopf, 1991)

For more than a century after the end of the war, the dominant historical and commemorative narratives revolved around commanders, armies, and battles in the eastern theater. Robert E. Lee. Ulysses S. Grant. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. The Army of Northern Virginia. The Army of the Potomac. Antietam. Gettysburg. When “western” elements crept into the story, they came from Tennessee or Mississippi, with the occasional—scandalous—appearance of Confederate bushwhackers in Kansas. Then in 1991 Alvin Josephy published The Civil War in the American West, a landmark historical survey of the conflict as it was waged west of the Mississippi River. The book involved Union and Confederate troops, western settlers, and Native Americans in a tale that admittedly feels old hat today. Moreover, Josephy’s “West” might now be considered too broad a description. Yet in the early 1990s, reframing the war as a western experience was groundbreaking and cleared the way for more nuanced versions of the Civil War’s Far West and the people who inhabited it.

Blood & Treasure: Confederate Empire in the Southwest

By Donald S. Frazier

(Texas A&M University Press, 1995)

Josephy’s The Civil War in the American West was geographically novel when it was published, but did not radically alter how historians conceptualized what the war was about. That development came four years later, in the form of Donald Frazier’s Blood & Treasure. Frazier blazed an entirely new trail, focusing on the Southwest—Texas, the Arizona and New Mexico territories, even parts of California and Mexico—to establish the imperial thesis that so many scholars of the Civil War in the Far West work from today. It was no surprise that Frazier, an eminent historian of Texas, traced the origins of pro-southern, pro-Confederate imperial ambitions to the expansionist tendencies of Texans, who were then turned loose by the Jefferson Davis administration to grab new prizes for the Confederacy. Though the likes of Henry Sibley made for poor Confederate conquistadors, their motive and intent, as documented by Frazier, forever changed the scope of the Civil War, whether traditional scholars wanted to admit it or not.

Blood & Treasure: Confederate Empire in the Southwest

By Ari Kelman

(Harvard University Press, 2013)

On November 29, 1864, Union colonel John Chivington led several hundred troopers against peaceful bands of Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians living along Big Sandy Creek in the Colorado Territory. Despite the village’s leader, Black Kettle, flying both the Stars and Stripes and a white flag to signal peace, Chivington’s men massacred more than 150 people, including dozens of women and children. Though it unfolded simultaneously with William T. Sherman’s famous “March to the Sea,” for more than a century the Sand Creek Massacre was categorized exclusively as an Indian campaign and detached from the American Civil War. That changed in 2013 with the publication of Ari Kelman’s A Misplaced Massacre, winner of the Bancroft, Watson-Brown, and Utley prizes. Much more than a rethinking of Chivington’s attack itself, the book narrates several competing—and often conflated—streams of history and memory that have emanated from Sand Creek since 1864. Kelman pays special attention to Native American voices, past and present, and places the story of the massacre’s complicated commemoration in a broader saga of American imperialism and Civil War memory in the Far West.

The Three-Cornered War: The Union, The Confederacy, and Native Peoples in the Fight for the West

By Megan Kate Nelson

(Simon & Schuster, 2020)

Megan Kate Nelson’s The Three-Cornered War weaves together stories with casts both enormous and diverse. It examines Civil War violence in the Old Southwest from the competing perspectives of the Union, the Confederacy, and the region’s native inhabitants. On one hand, that framework allows Nelson to chronicle how the warring governments both envisioned empires reaching from Atlantic to Pacific in the event of overall victory (a broadening of Frazier’s original concept), while also keeping track of the American Indians who actually lived there. On the other hand, while previous studies have integrated western Native Americans into the story of the Civil War, most often in military capacities, Nelson prioritizes the impact of military campaigns on Native American society and culture in that time—and she shows, really for the first time, the extent to which the harsh environmental features of the Far West played a key role in determining military matters and thus the region’s future.

West of Slavery: The Southern Dream of a Transcontinental Empire

By Kevin Waite

(University of North Carolina Press, 2021)

A common, if oversimplified, story about Daniel Webster is that the eminent Massachusetts senator did not believe slavery had a future in the Far West. Thus, he lost little sleep over the issue of its expansion into the western territories, confident it would be contained to the Deep South and there wither away. Kevin Waite’s West of Slavery makes clear that southern purveyors of railroads, mines, timber yards, agricultural schemes, and Pacific-bound freight operations—which is to say, all manner of southern capitalists (another update to Frazier)—had precisely the opposite belief. Just announced as the most recent winner of the Wiley-Silver Prize, Waite blueprints exactly how and why generations of southerners understood the Far West as an outlet for the spread of the “peculiar institution,” and the necessary backdrop for a southern commercial empire thriving from sea to shining sea. Coming on the heels of Nelson’s The Three-Cornered War and her illustration of how southern imperialism collided with Native American and environmental realities, Waite backtracks the concept of “Confederate Manifest Destiny” to its antebellum roots (that is, before it was Confederate). West of Slavery recounts how southerners in Congress lobbied to make their western dreams reality through various forms of coerced labor and peonage, then describes how embedded traces of pro-slavery culture continued to influence the way westerners approached the intersection of race and labor even after the Confederate experiment failed.

Matthew Christopher Hulbert is Elliott Assistant Professor of History at Hampden-Sydney College.