Historian George C. Rable

I was not one of those precocious Civil War enthusiasts who started reading Bruce Catton at the age of 10. Even when I was in high school, my tastes ran more to literature than to history. The first history book that left a serious impression was John F. Kennedy’s Profiles in Courage(1957). For some reason the chapter on the impeachment of Andrew Johnson and Kansas senator Edmund G. Ross, whose vote against convicting Johnson allowed the president to stay in office, struck me as fascinating—especially given the tumultuous politics of the late 1960s.

As it turns out, of course, the patronage-seeking Ross was not exactly a profile in political courage, but reading about that episode led me to an interest in the Reconstruction period and eventually to a college senior thesis on Johnson’s impeachment.

I had vague notions of becoming a high school math teacher, but at Bluffton College I had the great good fortune to take classes from John Unruh—an experience that changed my life. Unruh was a superb teacher who emphasized the importance of research in primary materials, historiographical sophistication, and clear writing. His magisterial, multiple-prize-winning (and sadly, posthumously published) The Plains Across: The Overland Emigrants and the Trans-Mississippi West, 1840–1860(1979) displays all these virtues. It quickly became a classic work that exemplifies the best the historical profession has produced. I can vividly recall how exciting it was as a college student to be introduced to serious history.

At that time, Bluffton students who maintained a certain class standing received a bookstore credit. One of my best choices in using that credit was Kenneth M. Stampp’s The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South(1956). I knew little about slavery but devoured this book, and decided that if this was the kind of history that professional historians did, I was more than interested. Unruh encouraged me to apply to graduate school at Louisiana State University, given my increasing interest in southern history and the fact that T. Harry Williams, who taught there, had recently won a Pulitzer Prize.

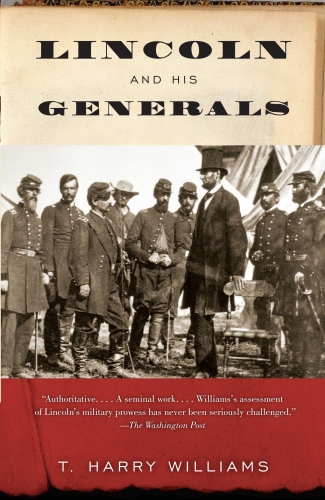

As an undergraduate, I had read Williams’ Huey Long(1970), and this proved to be a fine introduction to Williams the historian and the man. He grabs and keeps the reader’s attention with a combination of great style, ingenious use of oral history, and a cast of

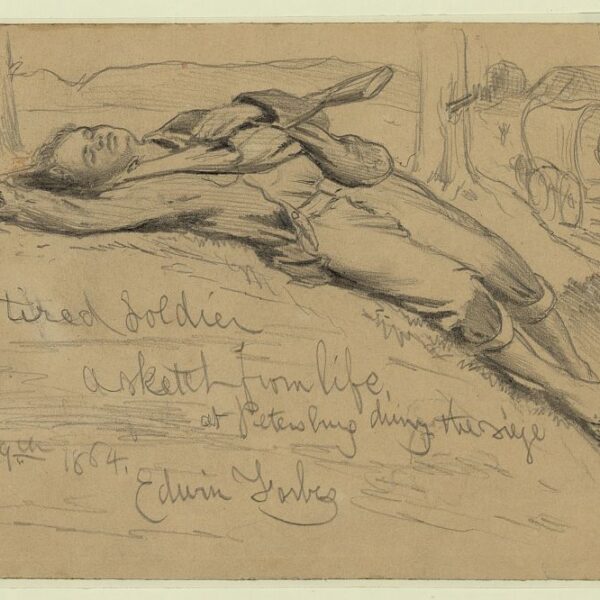

wonderfully colorful Louisiana characters. Williams always said he studied powerbrokers, starting with Abraham Lincoln early in his career and Lyndon Johnson toward the end of it. Indeed, reading Williams’ Lincoln and His Generals(1952) drew me further into the Civil War era. Combining fine narrative with provocative analysis, Williams presents Lincoln as a superb war leader. His tart judgments on generals including George B. McClellan and Joseph Hooker are especially memorable, but he also offers a model study that can reach both professional and lay audiences. And of course, I eventually did get around to Bruce Catton. My favorite of his works has always been the Army of the Potomac trilogy: Mr. Lincoln’s Army (1951), Glory Road (1952), and A Stillness at Appomattox (1953). Catton deserves all the praise he has received for his writing style, but I have been equally impressed with how well both his research and his narrative have held up over the years.

In about 1971, I developed a strong interest in the political history of Reconstruction. While working on my undergraduate thesis, I had carefully read Eric L. McKitrick’s fine study, Andrew Johnson and Reconstruction(1960). McKitrick’s portrait of Johnson as an outsider remains memorable, and he is especially good at portraying the fraught and complex relations between the president and Congress—something that seemed particularly relevant when I was reading it as the Watergate scandal unfolded. Equally apropos, though some 25 years old at the time I finally read it, Richard Hofstadter’s The American Political Tradition(1948) introduced me to a first-rate historical mind taking on familiar subjects with brilliant originality and mordant wit. I soon discovered that any book by Hofstadter was well worth reading.

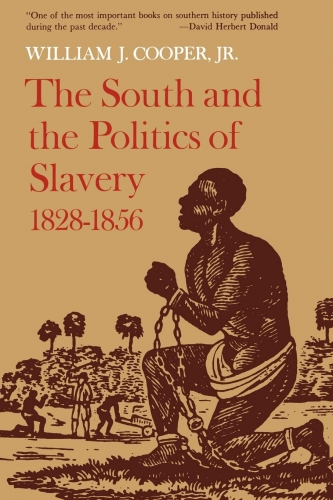

At LSU I developed a deeper interest in not only Reconstruction but also southern political history—largely spurred by classes taught by William J. Cooper. I was first exposed to many of the interpretations and evidence later presented in Cooper’s (1978) in his compelling and commanding lectures. Cooper presented his arguments for the centrality of slavery in antebellum southern politics—in the book and in his lectures—with abundant examples, absolute clarity, and great forcefulness. It is fair to say that Unruh, Williams, and Cooper not only greatly shaped my research interests but also set an example of how superb scholars can also be extraordinary teachers.

The South and the Politics of Slavery, 1828–1856

An interest in 19th-century southern (and American) politics soon broadened into a more capacious fascination with southern history broadly defined. To understand the history of the South requires an appreciation of its rich literary tradition. There is, for instance, the “Christ-haunted South” of Flannery O’Connor. I have read and reread O’Connor’s searing and perceptive short stories and novels, most conveniently in the Library of America volume Flannery O’Connor: Collected Works(1988). Through unforgettable characters and bizarre plots, O’Connor probes the southern psyche, most notably its religious underpinnings and pretensions. Her writing stimulated my slowly growing interest in religious history. Of course, there was no need to turn to fiction for fascinating and eccentric individuals. Drew Gilpin Faust’s James Henry Hammond and the Old South: A Design for Mastery(1982) deals with a peculiarly unappealing individual without succumbing to either preachiness or presentism. The reader enters the world of a slaveholder, politician, and deeply flawed human being—and in the process learns a great deal about southern history.

When it comes to great historians of the Civil War era, I would cite two more (and leave out a good number of deserving names). Any student of the sectional conflict should begin with David M. Potter’s posthumously published The Impending Crisis, 1848–1861(1977). Potter masterfully untangles complex issues such as slavery expansion and its impact on national politics. His lucid prose and brilliant analysis make his book a classic for both scholars and teachers. The same is true of another landmark study, James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era(1988). Turn to almost any page and enjoy a historian fully in command of his subject. I began reading this book in an airport and was hooked immediately. The mastery of theme, of detail, of anecdote, of quotation remains a stunning example of Civil War history at its best. McPherson’s work on the common soldier has certainly shaped my thinking about how to approach military history.

Throughout my career at the University of Alabama and now in retirement, I’ve tried to keep up with the flood of books on the Civil War era (and especially any well-edited primary sources), although I would advise students to keep reading the classic works in the field. Today, I live happily surrounded by books in virtually every room of the house and the garage. And more come in than go out.

GEORGE C. RABLE IS PROFESSOR EMERITUS, AND FORMERLY THE CHARLES G. SUMMERSELL CHAIR IN SOUTHERN HISTORY, AT THE UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA. HIS BOOKS INCLUDE FREDERICKSBURG! FREDERICKSBURG!(2002), GOD’S ALMOST CHOSEN PEOPLES: A RELIGIOUS HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR(2010), AND, MOST RECENTLY, DAMN YANKEES! DEMONIZATION AND DEFIANCE IN THE CONFEDERATE SOUTH(2015).

This article appeared in the Spring 2019 issue of The Civil War Monitor.