Just after seven o’clock on the night of April, 2 1867, George Maddox slipped out the backdoor of the Ottawa, Kansas, courthouse, hopped on his horse, and rode for Missouri. During the Civil War, Maddox served as a guerrilla under William Clarke Quantrill. Indicted for murder during the war for killing a man named John Zane Evans during Quantrill’s infamous 1863 raid on Lawrence, Maddox was arrested nearly two years later and transported to Kansas for trial. It was reported that following the reading of the verdict, he shook the hands of his attorney and a handful of unnamed friends who sat behind him at trial. Then, ever so furtively, Maddox met his wife, Nancy, behind the courthouse. She sat on horseback waiting for her husband holding the reins to his mount. From there, George and Nancy Maddox and the unnamed friends got the hell out of Dodge–that is, Ottawa–before news of the verdict hit the streets.1

Given the brutality and bloodshed associated with the raid on Lawrence and the guerrilla war more generally, the outcome of this trial may seem surprising. As dictated by the actions of the Union high command, national postwar practice was to allow Confederates – nearly all Confederates – to return to their peaceful lives. Only Champ Ferguson and Henry Wirz ever found the hangman’s noose for their wartime deeds. Some tensions continued to linger though; Americans on both sides found various ways to continue their grievances through commemorative efforts, politics, civil suits, criminal and terrorist acts, and even through the writing of history. These two feelings – that the war was horrible but that it was over and that the war had so unsettled society that there were still scores to be settled – have simultaneously coursed through the American soul ever since formal hostilities came to a close. The Maddox trial fully illustrates this reality.

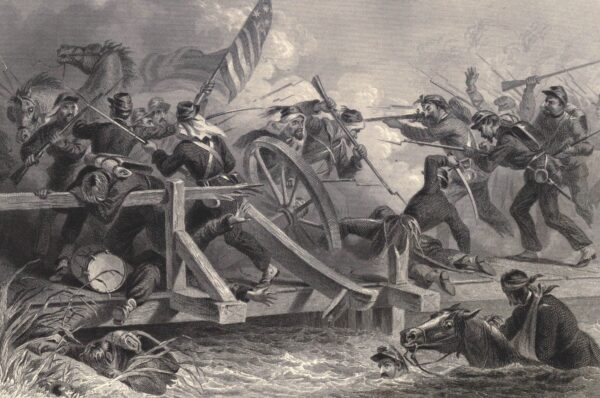

August 21 marks the sesquicentennial of William Clarke Quantrill’s raid on Lawrence, Kansas. The date serves as a reminder of one of the bloodiest, most brutal, and horrific events of the war in which approximately 300 southern sympathizing guerrillas killed nearly 200 unarmed male inhabitants of the town and razed most of the homes and businesses along the central thoroughfare of Massachusetts Street. The guerrillas poured into the town at daybreak with orders to kill every man or boy big enough to carry a gun, grab up anything of value that could be carried back to Missouri, and put everything else to the torch. Women were to be spared; although left without husbands, sons, their homes, and their means of survival, they were hardly unscathed. In the end, this was perhaps the greatest slaughter of white Americans by other white Americans. After a few hours of mayhem, the guerrillas mounted their horses and made for their haunts in the twisted and tangled woods of Missouri a few dozen miles to the east.2

There has never been a consensus on the cause(s) of the raid. The few guerrillas who left accounts of the war offer a range of reasons for the attack. Whether they cite the jayhawkers’ assaults on their own households – killing old men and boys, the abuse of white women, the liberation of slaves, and the destruction of their homes – or the collapse of the makeshift women’s prison in Kansas City or the opportunity to reclaim household loot or the Union army’s no quarter policy, each guerrilla suggests that the attack was in keeping with their informal, household-based system of warfare. From the perspective of the Kansan, there was nothing logical or systematic about the attack; it was chaos. One eye-witness who survived to write about it called the raid, “Hell let loose.”3

A great many readers know George Maddox, or at least you know what he looked like. Maddox’s image appears and reappears in books and on internet posts about the war, and rightly so. He was quite the peacock. In terms of popularity, the picture of the nattily dressed Maddox, legs-crossed, brandishing an uncommon brace of revolvers for a guerrilla appears more often than any other picture of a guerrilla with the possible exceptions of the wartime images of Jesse James and “Bloody” Bill Anderson (in life and death). Beyond this man’s style the camera captured a certain presence that seems to reach out through the decades. Looking at his image on your laptop screen, Maddox calmly stares right back at you from the 1860s.4

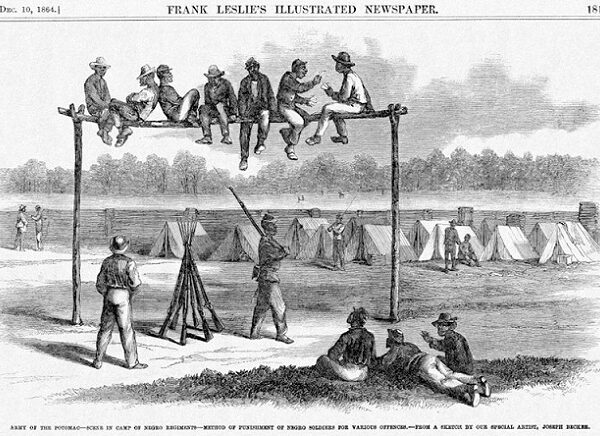

The testimony, at least for the prosecution, did not paint Maddox as a unique man among his guerrilla comrades. He was not brought to trial because he did the most killing or even because he was the most infamous raider at Lawrence: both Bill Anderson and Larkin Skaggs seem to have been at or near the top of those two lists. On the stand, John Evans’ father, James, offered unconvincing testimony that Maddox had been the one who killed his son. Other notable testimony came from half a dozen black men and women who, while still enslaved back in Missouri, overheard Maddox talking about raid after the guerrillas had returned to their home neighborhoods. The implication was that the accused was almost certainly present in Lawrence on August 21. The defense brought a number of their own witnesses. Sheriff Ogden, who had arrested Maddox, and a Mr. and Mrs. John Speer, who lost a son in the raid, offered rebuttal accounts that challenged testimony from the prosecution witnesses. Other witnesses – a few who were predictably sympathetic to Maddox’s cause like his stepmother – claimed to have seen him in Missouri at the time of the raid. This claim was confirmed by a black man named Henry Neal who also said he saw Maddox far from Lawrence during the raid. The defense argued that the reason for his absence during the raid was that this ostrich plume wearing and pistol brandishing man was too sick to ride along for the most legendary raid the guerrillas would make.5

According to the newspaper accounts, it took the jury ten minutes to acquit Maddox for the “felonious killing of one John Zane Evans.” In a vacuum, the verdict was well-supported by the evidence presented in the case. It is easy to see that there was enough doubt placed in the minds of the jury regarding the presence of the accused in Lawrence on that day or the likelihood that Maddox was Evans’ assailant. Either way, it is difficult to know what manner of debate could have taken place in ten minutes, or if there was any debate at all.6

The trial of George Maddox took place less than two years after the end of the war and less than four years after the raid on Lawrence. As the crow flies, Ottawa is no more than twenty-five miles south of Lawrence. The change of venue was no doubt helpful to the defense, but the men in the little town of Ottawa were still Kansans. Well aware of the recent history, Judge Valentine included in his instructions to the jury: “You cannot convict the defendant of this charge, because he may have been a bushwhacker or rebel, or because he may have been engaged in any unlawful enterprise, except the one that resulted in the death of John Zane Evans.” So close to the war, it would have been understandable if this directive had fallen on deaf ears.7

The verdict was not popular with everyone. Mrs. John Speer had visited Maddox in jail before the trial in an attempt to learn about her son’s fate but the guerrilla had nothing to tell her. After seeing the accused Mrs. Speer attended the trial with her husband and brought with her to the courthouse a derringer nestled in the pocket of her dress. As the story goes, if the jury acquitted Maddox, she planned to take her vengeance and shoot him down. Luckily for Maddox, Mrs. Speer presumed the jury would deliberate for a while, certainly more than ten minutes. When the verdict was read, she was not present, allowing the guerrilla to make his escape.8

Regardless of how the trial turned out, Maddox was a killer. It is tough to know exactly who killed John Evans, especially given the confusing circumstances of the slaughter on August 21, 1863. The odds alone make it unlikely that it was Maddox, assuming he was there in the first place. That does not mean he did not kill other men on that day or during the days before or after the slaughter.

Postwar judgment of wartime deeds is a nasty and difficult task. It seems that the jury viewed this killer within the context of a war that saw more American men become killers than any other. The war was over and the jurymen must have felt that it was not their place to cast stones. For some, however, the war never ended. Maddox was guilty of being a bushwhacker, a verdict that warranted immediate death just as it had during the war itself. To these people, it was never a matter of stones but rather of eyes and teeth.

Joseph M. Beilein, Jr. is an Assistant Professor of History at Penn State University-Behrend.

1“The Maddox Trial,” Daily Tribune, April 4, 1867, found at http://www.franklincokshistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/The-Kansas-Daily-Tribune-Maddox-trial-evidence.pdf. Other descriptions of the trial come from Edward Leslie, The Devil Knows How to Ride: The True Story of William Clarke Quantrill and His Confederate Raiders (New York: Da Capo Press, 1998), 243-244.

2Thomas Goodrich, Bloody Dawn: The Story of the Lawrence Massacre (Kent: Kent State University Press, 1991); Albert Castel, William Clarke Quantrill: His Life and Times (New York: F. Fell, 1962), 122-143; Richard Brownlee, Gray Ghosts of the Confederacy: Guerrilla Warfare in the West, 1861-1865 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1958), 110-127.

3John McCorkle, Three Years with Quantrill: A True Story Told by His Scout, written by O.S. Barton (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1992 [1914]), 122-123; William H. Gregg, “A Little Dab of History without Embellishment,” Western Historical Manuscript Collection, Columbia, Missouri (Hereafter, WHMC), 46-52; http://www.kancoll.org/books/cordley_massacre/quantrel.raid.html. For the newest analysis regarding the concept of household war see Kristen Streater, “’She-Rebels’ on the Supply Line: Gender Conventions in Civil War Kentucky,” in Occupied Women: Gender, Military Occupation, and the American Civil War, ed. By LeeAnn Whites and Alecia Long (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2009), 88-99; LeeAnn Whites, “Forty Shirts and A Wagon Load of Wheat: Women, the Domestic Supply Line, and the Civil War on the Western Border,” Journal of the Civil War Era, Vol. 1, No. 1 (March 2011), 56-78; Joseph M. Beilein Jr., “Household War: Guerrilla-Men, Rebel Women, and Guerrilla Warfare in Civil War Missouri,” (University of Missouri, Dissertation, 2012).

4For deeper analysis regarding the rather particular appearance of the guerrillas, see Joseph M. Beilein Jr, “The Guerrilla Shirt: A Labor of Love and the Style of Rebellion in Civil War Missouri,” Civil War History Vol. 58, No. 2 (June 2012), 151-179.

5I encourage readers to go to visit the Franklin County, Kansas page on the Maddox trial and examine the trial documents which are linked at the bottom of page: http://www.franklincokshistory.org/people-2/people/maddox-george-w/.

6http://www.franklincokshistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/The-Kansas-Daily-Tribune-Maddox-trial-evidence.pdf; Leslie, The Devil Knows How to Ride, 243-244.

7http://www.franklincokshistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/The-Kansas-Daily-Tribune-Valentine.pdf; Leslie asserts without any evidence that the jury was bribed. Clearly this is a possibility, as is intimidation. However, there is nothing documented that allows me to make that conclusion. Rather, the documents support a very different conclusion. John Speer, newspaper editor and father of a young man most likely killed at Lawrence, said in his coverage of the trial “That the jury was a fair one, none doubted; that the trial was impartial all conceded.” See http://www.franklincokshistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/The-Kansas-Daily-Tribune-Maddox-trial-evidence.pdf.

8http://www.franklincokshistory.org/people-2/people/maddox-george-w/.