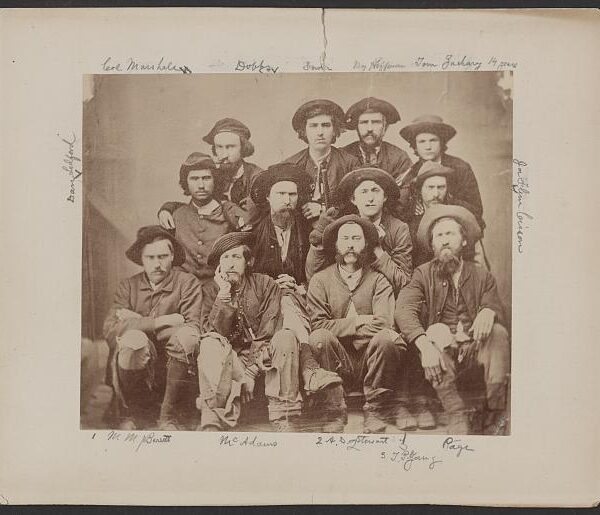

Lieutenant Robert Pryor James, Co. E, 20th North Carolina Infantry

This will be my final column for the “American Iliad” series, a project I undertook five years ago, animated by the conviction that certain stories and characters in the Civil War were fixed in the American imagination by their mythic resonance. I made it my task to tease out what that resonance might mean. At the outset I recognized that “foundational to the American Iliad is the conviction that the conflict was not a struggle between darkness and light, freedom and tyranny, but rather between two sides, equally gallant, committed to different but morally equivalent visions of the American republic, and therefore caught up in a tragedy larger than themselves, ‘a war of brothers.’”[1] I never believed in that moral equivalence, though for a long time it didn’t bother me; it was the founding myth on which the American Iliad was based. But over the years I have found the insistence on that equivalence harder to ignore, particularly in light of the recent protests that have thrown into bold relief the pain it causes so many of my countrymen—countrymen who happen to be black. Put simply, my continued involvement with the column requires me to ignore something I can no longer ignore.

I dislike the pose of superiority this stance often assumes. I’m a Carolinian born and bred. One side of my family has roots deep in the sandy loam of South Carolina; the other side lived for 10 generations on the North Carolina coastal plain. As a youth I knew almost nothing about my South Carolina ancestors—not even that one of them had fought under the legendary partisan Francis Marion—but I identified closely with my Tar Heel heritage and the 125,000 North Carolina troops who, as the proud boast went, were “First at Bethel, Farthest to the Front at Gettysburg and Chickamauga, and last at Appomattox.”[2]

For many years I had no idea that 5,000 white and 5,000 black Tar Heels served in the Union army.[3] I doubt it would have made a difference to me. My sympathies were thoroughly with the Confederacy, not because I regarded slavery as in any way just or harbored a belief in white supremacy—no more than I did in the racism that I and most southern white children raised in the 1960s imbibed unthinkingly. My loyalties were reflected in the person of Colonel Robert Williams, the main character in a novel I wrote at age 11—whose reasoning was much like Robert E. Lee’s. On the first page, my hero ponders the secession of South Carolina and wonders what he would do if war began and his native North Carolina seceded. “How would he turn? Toward his country or to his state? He did not wish to take up arms against his country, but neither did he want to draw his sword against his beloved North Carolina.”

His anguish is short-lived. Two paragraphs later a lieutenant arrives at the behest of his superior, demanding to know what course Williams will take in case of war. Seething with barely suppressed anger, Williams responds, “Lieutenant, I have served with the Army for 25 years. I have fought for my country and my God. But I cannot draw my sword against my state, which I have known and loved since I first came to this Earth. She is an Eagle, Lieutenant, proud and strong and free, and if she dares to leave the Union, I will follow.” While Williams soon joins the Confederate army as a brigadier general, it remains clear throughout that he is only fighting for his homeland.

My point, in all the foregoing, is to establish my bona fides as a white southerner proud of his Confederate heritage. I was proud of it at age 11. I remain proud of it 50 years on. But I long ago became aware—as have many white southerners—that mingled with this pride must be a consciousness of its involvement in one of the darkest aspects of American history. My ancestors not only fought for the Confederacy but also enslaved dozens of black southerners—bought them, sold them, and held them in bondage as long as they could. This tangle creates an existential dilemma from which I see only two means of escape.

The first is to convince myself that slavery was somehow just, or that, at the very least, white supremacy—however one may want to camouflage it—is defensible. As a college professor I’m supposed to live in some notional ivory tower, far removed from such sentiments. As a regular at my neighborhood bar I hear them all the time.

The second is to quit being a white southerner in favor of simply being a southerner, full stop: proudly incorporating into my own heritage the endurance of fellow southerners (who happened to be African-American) through generations of bondage; the music, cuisine, and folkways they created; the gallantry of black southerners who bled and died in America’s many wars, including hundreds of black Tar Heels. I could choose to embrace the heroism of the African-American college students who in 1961 took seats at a Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina—reserved by custom for whites—and asked to be served like any other customers.[4] I could even embrace the valor of an actual Robert Williams—one Robert F. Williams—who welded the African-American domestic workers and military veterans of Monroe, North Carolina, into one of the most militant and fearless chapters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.[5] That’s an appealing choice to make.

Henry King Burgwyn

None of this means rejecting the valor of my ancestors. I am a collateral relative of Henry King Burgwyn, the 21-year-old “boy colonel” of the 26th North Carolina who died at the head of his regiment at Gettysburg. I can take pride in that, as I can in the dozens of yeoman farmers from my parents’ home counties—the friends and neighbors of my kinsmen—who took up arms and did their duty through four years of hell.

I know that some discount and even despise the courage of such men. I reject that posture: Throughout our history we have honored our servicemen and women regardless of how we feel about the causes for which they fought. What I cannot condone is the appropriation of their valor in the service of white supremacy. As a child I once saw a pamphlet extolling the “letter written in blood” by a dying Confederate officer at Gettysburg (actually written in pencil but stained with the man’s blood). “Major,” it read, “Tell my father I died with my face to the enemy.”[6] I will never forget the declaration that accompanied the caption, written by the governor of North Carolina himself: “It is a message from our race to the world.” Coming in the midst of the struggle to preserve legal segregation, it was not hard to guess what race he meant. Those who lament the supposed “loss of history” as Confederate statues are removed or toppled headlong from public spaces ought to read the speeches made on the day of their dedication. Nearly all of them extol “our race of men” and “the common heritage of our race.”[7] The dedication to the North Carolina Memorial at Gettysburg—for obvious reasons my favorite of all monuments on that battlefield—speaks repeatedly in terms such as this: “The chief interest of the war lies in the fact that it was a genuine conflict of idealisms, fervently held and loyally followed by both sides.”[8] Lost in this formulation is the experience of African Americans—those liberated by the war and those who gave their life’s blood to make that liberation possible.

And lest this mingling of white supremacy and ordinary white valor seem somehow innocent, as a Tar Heel I must confront a passage from a speech given at the 1913 dedication of the Confederate soldier, popularly dubbed “Silent Sam,” that was recently pulled down from its pedestal at the main entrance to the University of North Carolina campus at Chapel Hill. Toward the end of his address the orator permitted himself a personal anecdote. “One hundred yards from where we stand,” he declaimed, “less than ninety days perhaps after my return from Appomattox, I horse-whipped a negro wench until her skirts hung in shreds, because upon the streets of this quiet village she had publicly insulted and maligned a Southern lady, and then rushed for protection to these University buildings where was stationed a garrison of 100 Federal soldiers. I performed the pleasing duty in the immediate presence of the entire garrison, and for thirty nights afterwards slept with a double-barrel shot gun under my head.”[9]

Heritage, not hate, the slogan goes. The fact is that we must deal with both. We can and should honor Confederate valor and fidelity to duty. But we can no longer afford a national myth that equates a struggle for human freedom (however imperfectly realized) with a struggle for the privilege of horse-whipping a woman and bragging about it to an approving crowd, or lynching black men by the hundreds, or denying American citizens basic civil rights, simply because their skin was dark. We must bid goodbye to all that.

MARK GRIMSLEY, A HISTORY PROFESSOR AT THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY, IS THE AUTHOR OF SEVERAL BOOKS, INCLUDING AND KEEP MOVING ON: THE VIRGINIA CAMPAIGN, MAY–JUNE 1864(2002) AND THE HARD HAND OF WAR: UNION MILITARY POLICY TOWARD SOUTHERN CIVILIANS, 1861–1865(1995). HE HAS ALSO WRITTEN MORE THAN 50 ARTICLES AND ESSAYS.

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2020 issue of The Civil War Monitor.