Emancipation directed by Antoine Fuqua. Length: 2 hours, 12 minutes. Premiere: December 9, 2022.

Antoine Fuqua’s Emancipation could be one of this century’s great movies about self-emancipation. Not because of its fragile historical accuracy, or because it stars Will Smith, but because it lives up to its title: portraying what it took for some enslaved people to obtain freedom. Despite such a riveting story, many people may not see the film because of controversy surrounding the star’s behavior at last year’s Oscar ceremonies. However, this is not a movie about Will Smith; it is about Peter and his struggle to free himself from enslavement and join the Union army’s 3rd Louisiana Native Guards Infantry Regiment—all in the wake of President Abraham Lincoln issuing the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863.

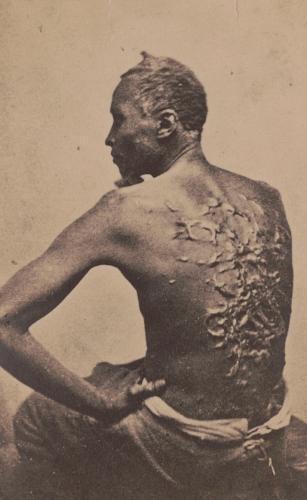

“Whipped Peter,” in a photo from April 1863.

There are not many historical sources on Peter, the movie’s protagonist. First identified as “Whipped Peter” and “Poor Peter,” he was later identified as Gordon before historians confirmed his name was more than likely Peter. There is no documented last name for Peter, but as he was enslaved on the Lyons Plantation, about 40 miles from Baton Rouge, Louisiana, that would probably have been his last name before he was free to change it. That brings us to the heart of the movie, Peter’s emancipation. The movie takes liberties with his story, and instead of relying on his harrowing 10-day journey through the Louisiana swamps, has him fighting off every beast he encounters from alligators to enslavers. When Peter makes it to Union lines, he is quickly made a soldier and seems to win the May 1863 Battle of Port Hudson before the movie ends. But in April, during Peter’s medical examination, doctors had seen the horrors of slavery embedded in his back and wanted to circulate his image through the nation. First as a photograph and later a widely circulated carte de visite in April 1863, the proof of what enslaved people endured in the South was too much for many to bear. The image galvanized more of the northern populace to get behind abolition, which furthered support for the Union army that summer.

While all of these are situations Peter finds himself in, there are few historical facts in the movie. The imprecisions of Emancipation are quite varied—and can feel jarring—but the source material was simply not there for the moviemakers. While the original Peter had a long journey through the Louisiana swamps—one he almost did not survive—he was no hero who saved others and nearly ended a battle himself. In truth, he was a man who was beaten so severely that he was pushed to try for freedom rather than wait for the next assault by a white man. When Peter made it to Baton Rouge, it took days for Union doctors to even see him, let alone document his scars. Then his story became more legend than fact as abolitionists used the image as a lightning rod for their movement. Peter first worked as a guide before joining the 3rd Native Guards, one of the Union army’s first African-American regiments, and while he did charge Port Hudson with Captain André Cailloux and hundreds of other black soldiers on May 27, 1863, they won no battle that day. The 1st and 3rd Native Guards Infantry Regiments, part of Nathaniel P. Banks’ XIX Corps, were repulsed on every charge and eventually the Union army was forced to retreat. They did, however, resort to hand-to-hand combat during at least two of those charges, one of which resulted in the death of Captain Cailloux. After the XIX Corps retreated, Port Hudson became a protracted siege because Banks was not a war general and knew little military strategy for taking the citadel. Port Hudson fell to Union control only after Ulysses S. Grant seized nearby Vicksburg, Mississippi. There was no heroic battle, just a southern commander realizing that if he did not surrender, Grant would send forces to assist Banks in capturing Port Hudson. The social and military history of Emancipation is erroneous; what Fuqua and his writers have done instead is tell a story of self-emancipation in Louisiana.

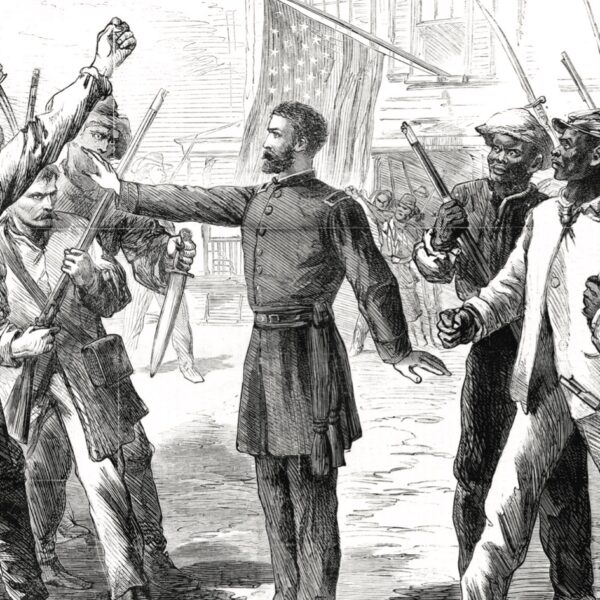

Will Smith (center) as Peter in Antoine Fuqua’s movie “Emancipation.”

Emancipation could be for the self-emancipation narrative what The Birth of a Nation (1915) was for the Lost Cause. Historians of the 19th century are familiar with stories about maroons, people descended from Africans who formed settlements away from slavery; in Louisiana, such men and women lived in the swamps and fought against many of the same beasts that Peter faces in the movie. Additionally, thousands of enslaved people freed themselves and set off through the swamps, not all of them surviving the perilous journey. What Emancipation gets right is what the photographic image of Peter accomplished in 1863: capturing the reality of slavery and its cruelties. It matters little if the character Peter engaged in or suffered all of the movie’s actions; what does matter is that many enslaved people in Louisiana endured them during their journey to free themselves. Antoine Fuqua gives us one movie that tells the stories of many thousands. It gives the moviegoing public a visual sense of what it looked like for someone running from dogs, leaving a dead friend behind, or having to kill to survive.

Emancipation is a film about Peter and the self-emancipation narrative, and the movie should be acknowledged as such. This reviewer has but one suggestion: See it. Do not watch it as I did with a note pad and pen, counting the historical inaccuracies. Do not watch thinking you will learn all there is about the self-emancipation narrative. Do not watch believing you forgive Will Smith for his real-life behavior. Emancipation should be watched for what it is, a historical fiction, and then used as a tool by educators who want to teach what self-emancipation meant in states such as Louisiana. Peter had to travel 40 miles, and went through hell to reach whatever freedom there was. Ask your students, what about those who traveled hundreds of miles? What about enslaved people who emancipated themselves before the war when many northerners were ambivalent about slavery? What about the people who never made it, their pictures never taken, their lives never noted? If Emancipation is seen, these questions might be asked—and answered.

Anthony J. Cade II is a retired United States Marine, PhD candidate at the George Washington University, and military historian with the federal government. His research is focused on the subaltern of the American Civil War, specifically immigrants and African Americans. His is currently working on his dissertation, which is focused on the Louisiana Native Guards, one of the Union army’s first successfully constituted African-American regiment during the Civil War.

Related topics: African Americans, emancipation