The December 1912 issue of The Confederate Veteran carries a list of eleven members of the Joe Johnston UCV Camp No. 94 of Mexia, Texas, who died between July 1911 and July 1912. Midway through the list is a brief, two-line mention:

RISIEN, SAMUEL — Born in England; went down on steamer Titanic April 4, 1912 [sic.]. Engineer on Confederate steamer Alabama under Admiral Raphael Semmes.

Samuel Beard Risien was born on June 3, 1842, in Kent, in the United Kingdom. His early life is unknown, as is how he came to be a member of Alabama‘s crew. According to information provided decades later to census takers, he didn’t emigrate to the United States until 1869. Risien brought with him his wife of two years, Mary Louise Lellyet, and their young son, Samuel W. Risien. They lived for a while in Michigan, where two more children were born, but eventually settled in Groesbeck, in Linestone County, Texas. They were there at the time of the 1880 census and Samuel working as a carpenter.

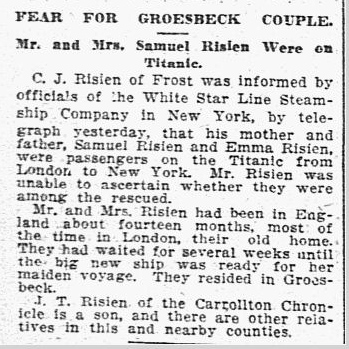

Mary seems to have died sometime later, because around 1890 Samuel married Mary’s widowed sister, Emma Lellyet. Samuel and Emma had no children of the their own, and with his children from his previous marriage grown, he and Emma traveled a great deal. An item in the April 20, 1912, edition of the Dallas Morning News notes that the couple had made no fewer than fifteen trips to Europe, a remarkable total for that day—especially for people of relatively modest means. Samuel may have engaged in other money-making enterprises on the side; sometime around the turn of the century he was convicted and fined $100 for running an illegal lottery in which a horse and buggy were the prize. Risien successfully appealed the conviction, arguing that because all the 200 tickets had been sold—thus guaranteeing that someone would win the prize—the operation he was running was not a lottery, which was against the law, but a raffle, which was totally legit. At the time of the 1910 U.S. Census in April, Samuel and Emma Risien were renting a home in Galveston, where Samuel’s occupation was listed as “hotel proprietor.”

Sometime early in 1911 Samuel and Emma traveled to the UK to make an extended visit there. Family tradition today says they continued on to South Africa, where Emma’s family has interest in diamond mines, but that’s not mentioned in contemporary news accounts of their loss on the ship. They were away from the United States about fourteen months. In April 1912 they began their return voyage to the U.S. as Third Class passengers on Titanic. Samuel and Emma were solidly middle class, but there were many such people “traveling third” on Titanic that voyage. They were looking forward to the trip; a week or more before sailing Samuel had sent a postcard to his son:

Sometime early in 1911 Samuel and Emma traveled to the UK to make an extended visit there. Family tradition today says they continued on to South Africa, where Emma’s family has interest in diamond mines, but that’s not mentioned in contemporary news accounts of their loss on the ship. They were away from the United States about fourteen months. In April 1912 they began their return voyage to the U.S. as Third Class passengers on Titanic. Samuel and Emma were solidly middle class, but there were many such people “traveling third” on Titanic that voyage. They were looking forward to the trip; a week or more before sailing Samuel had sent a postcard to his son:

About the time you get this we will be leaving for N. York We expect to sail on the new ship “Titanic” largest in the world and her trip (45,000 tons) two more papers I think will be all I can send We shall sail from Southampton on April 10th that is if they can get coal enough to go on. it is getting very scarce and dear Both well, Papa

Neither Samuel’s nor Emma’s remains were identified in the aftermath of the disaster.

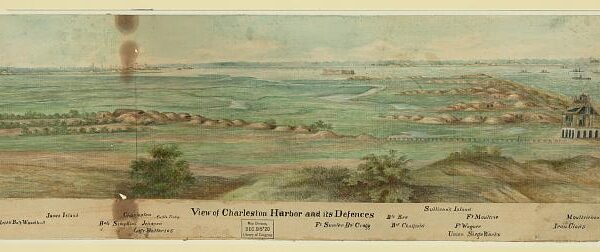

So, was Samuel Risien a crew member of the famous Confederate raider Alabama? It appears so, although the claim by his UCV camp seems to be the only evidence of that. He probably wasn’t actually one of the ship’s engineers, as suggested by the Confederate Veteran; Alabama‘s officers are well known. He could well have been one of the engine room crew, but independent verification is difficult. Alabama‘s construction, fitting out, and manning in the UK were (very imperfectly) kept under wraps due to Britain’s neutrality in the conflict. Many of her crew shipped under aliases. The Alabama never touched a Confederate port, and those records carried onboard ended up at the bottom of the English Channel. As a result, despite the best efforts of historians, much detailed information about the raider remains shrouded in the haze of time. This was well understood even in the 19th century; one of the better-known first-hand accounts of the ship, Philip Drayton Haywood’s “Life on the Alabama, by One of the Crew,” appearing in Century Magazine‘s famous Battles & Leaders series alongside memoirs written by the ship’s real executive officer and ship’s surgeon, proved to be an outright fraud.

We know nothing about Samuel and Emma’s time aboard Titanic, but it’s fun to speculate. Did they spend part of that first evening aboard out on the after deck, bundled against the early April chill, as the White Star Liner made her penultimate port call at Cherbourg? Did they watch as the tender Nomadic came alongside, ferrying First Class passengers like the Duff Gordons, Maggie Brown, and Ben Guggenheim out to the ship? Did Samuel take the opportunity to tell Emma (perhaps for the umpteenth time) his account of the furious battle with U.S.S. Kersarge, that had happened just outside the harbor nearly fifty years before?

I’d like to think so.

Andy Hall is a Texan and Southerner by birth, residence and lineage, with a family tree full of butternuts. With a background in history, museum studies and marine archaeology, Hall also writes at his own blog,Dead Confederates.

Image Credit: Dallas Morning News, April 18, 1912; Smithsonian Institute.