David Cornwell, formerly an infantryman in the 8th Illinois Infantry and a veteran of Shiloh, was serving with Battery D, 1st Illinois Artillery, in the summer of 1862. Stationed not far from Jackson, Tennessee, his mess obtained a cook, an enormous African American who called himself Jack Jackson. Standing six-and-a-half feet tall, powerfully built, and never wearing shoes because of the size of his feet, Jack told Cornwell his story.

Jack had been a slave somewhere in the “Yazoo district” of Mississippi. When his overseer tried to whip him, Jack grabbed the whip, struck the overseer in the head, and “he drop like a stone.” Jack didn’t stick around to see if the man was still alive. He grabbed an ax, headed for a nearby swamp, cut out a club from an ironwood tree, and threw the ax away. Hounds could be heard in the distance, getting closer. “I tell yer Mister Sojah, dem dogs … pitch inter me savage like … so I jest killed ebry one of dem wid dat club.” Jack continued northward until he came into the Union camp near Jackson, Tennessee, where he met Cornwell.1

Time passed, and Jack was reassigned as a mule driver. Cornwell’s battery moved gradually to the south, into northern Mississippi, and then into northeastern Louisiana, along the Mississippi River. One day in April 1863, the Adjutant General of the United States, Lorenzo Thomas, addressed the men of General John A. Logan’s division, including Cornwell’s battery. Thomas announced the new policy of recruiting black regiments, and was there to seek experienced white veterans to serve as officers in the new regiments. Cornwell volunteered, hoping for a promotion to captain. He received a lieutenancy instead, but was still pleased at his new rank. Jack Jackson was among the first recruits.

Cornwell and his captain, Corydon Heath, soon set out to scour the countryside for new recruits. Each officer was responsible for recruiting his company up to strength. Until they did so, they would still be paid at their old rank and be considered on “detached service” from their old regiment. Only when enough men had been recruited to fill the company would Cornwell, Heath, and Second Lieutenant Edward Smith obtain their new ranks and pay. This meant all of the officers in the new regiments had extraordinary incentives to recruit as many men as they could, as fast as they could. Cornwell and Heath would lose no time.

After two full days visiting various plantations, often drawing good crowds, Cornwell and Heath still had nary a recruit. Lying awake at night, puffing thoughtfully on a cigar, Cornwell wondered if he should go back to his battery. The former slaves had it made, he thought. Their masters had all fled to the West, they were now free to come and go as they pleased, and needed to do little work as there were still enough foodstuffs in their masters’ larders to keep them well-fed for a time. How could the army compete with that?

Cornwell thought about Big Jack. As Jack had been following the army for nearly a year, Cornwell had promptly made him a sergeant. Cornwell wondered if he might not have more success recruiting among the blacks if Jack accompanied him. Cornwell told Heath to stay in camp the next day, and Jack went out with him instead. Cornwell rode Heath’s fine horse and Jack came along behind, mounted on a mule. Cornwell laughed to himself at Jack’s appearance: “His large bare feet just cleared the ground and the sleeves of his jacket, … stopped about half way between the elbow and wrist, while his trowsers were practically knee pants.” But Jack didn’t seem to mind.2

When they reached the first plantation, they drew a crowd. “They did not pay much attention to me,” observed Cornwell, “but riveted their eyes on Jack, whom they must have thought a brigadier at least.” Jack lined the men up “according to rank,” said Cornwell—placing each man in order of height. (Jack deserved more credit than Cornwell gave him. Jack was placing the men in rank [a line of men]—not organizing them by rank [positions of authority].) After two more plantations, Cornwell and Jack came back to camp with 21 new recruits. Captain Heath was astonished, and swore them in.3

Their company began to grow, as did the rest of their regiment. The 9th Louisiana Infantry, African Descent, under the command of Colonel Hermann Lieb, took its station at Milliken’s Bend, Louisiana. Cornwell began running his men through their paces, instructing them on basic formations, issuing them arms and uniforms, and setting up a range for target practice (where the results were disappointing).

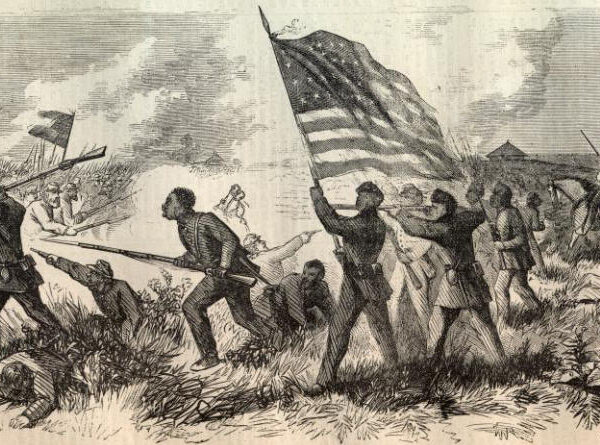

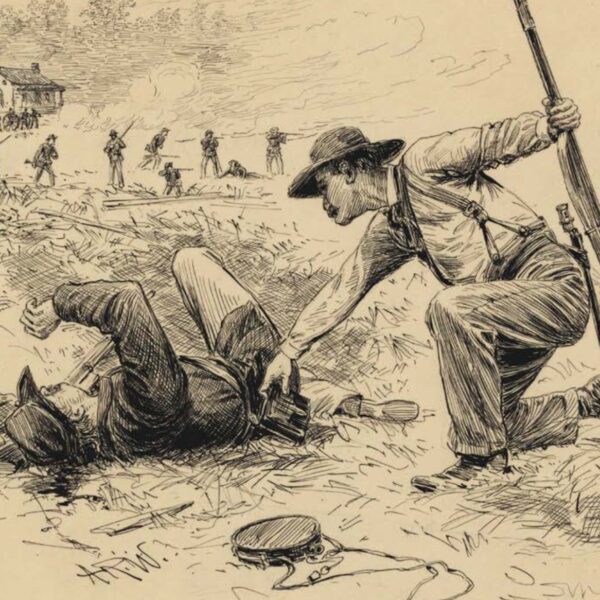

Then, on June 7, 1863, before sunrise, a brigade of Texans under the command of Brigadier General Henry McCulloch attacked the Union outpost. Defended by the 9th Louisiana and other regiments of the “African Brigade,” along with about 120 men from the all-white veteran 23rd Iowa Infantry, the fight was brutal. The Rebels came on with shouts of “no quarters for white officers, kill the damned abolitionists, but spare the niggers.” Captain Heath’s company was at the far left of the Union line, and was quickly overwhelmed. Cornwell was standing nearby with the reserve, and called out to his men, “Now bounce them Bullies” and charged forward. “Big Jack Jackson passed me like a rocket,” he later wrote. “With the fury of a tiger he sprang into that gang and smashed everything before him…. There was nothing left of Jack’s gun but the barrel, and he was smashing every head he could reach. He had repeatedly been bayoneted, but seemed unmindful of such injuries.” After the surge forward, Cornwell withdrew his men a short distance, “but for Jack I could do nothing. On the other side [of the levee] they were yelling, ‘Shoot that big nigger, shoot that big nigger.’” Despite his wounds, Jack fought on, almost daring the enemy to strike him down. “Then a fatal bullet reached his head and he went down full length on the levee,” wrote Cornwell.4

Decades later, early in the 20th century, David Cornwell typed out his memoirs at his home in Allegan, Michigan. He remembered his friend Jack Jackson, and despite lingering prejudices and condescension toward blacks, Cornwell was clearly fond of this man. No other African American is written about in such detail, and no other enlisted man is given such prominence in Cornwell’s account of the fight at the Bend. Cornwell’s memoir portrays Big Jack Jackson with respect, admiration, and good humor—despite an often paternalistic attitude. He was a man of his times, and he held Jackson in greater admiration than his sometimes disparaging language might indicate. Early regimental records for the 9th Louisiana Infantry, African Descent, were lost in the battle. Cornwell’s memoir, then, becomes the only source that documents the story and heroism of Big Jack Jackson.

Linda Barnickel is an archivist and freelance writer with master’s degrees from the University of Wisconsin – Madison and The Ohio State University. Her new book, Milliken’s Bend: A Civil War Battle in History and Memory (LSU Press), chronicles an overlooked yet significant battle during the Vicksburg Campaign, in which former slaves met their Confederate adversaries in one of the bloodiest and most controversial small engagements of the war.

1 John Wearmouth, ed. The Cornwell Chronicles: Tales of an American Life… (Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, 1998), 147.

2 David Cornwell Memoir, p. 123, Civil War Miscellaneous Collection, U.S. Army Military History Institute.

3 Cornwell Memoir, pp. 123-124.

4 Cornwell Memoir, pp. 136-137, 133.

Cover Art courtesy of the author.