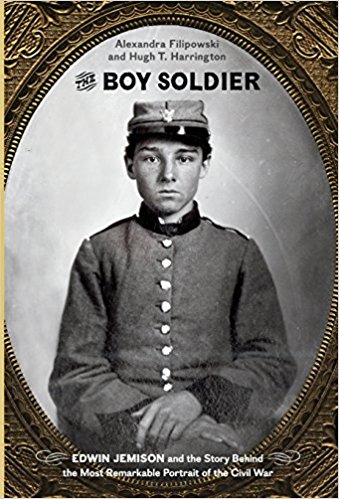

The Boy Soldier: Edwin Jemison and the Story Behind the Most Remarkable Portrait of the Civil War by Alexandra Filipowski and Hugh T. Harrington. Westholme Publishing, 2016. Cloth, ISBN: 978-1-59416-264-0. $26.00.

At the beginning of the American Civil War’s Centennial in 1961, the famed writer Robert Penn Warren remarked that, “the Civil War is our only ‘felt’ history—history lived in the national imagination.” The painful memories and lived realities of fallen American soldiers in countless military conflicts beyond the Civil War—both historically and now—cast skepticism on Warren’s thesis, but the Civil War undoubtedly changed how nineteenth century Americans visualized their memories of the past. Previous conflicts in American history like the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 can only be visually remembered through the interpretive hands of painters, sculptors, and sketch artists. But the Civil War, thanks to the invention of the daguerreotype in 1839, has been absorbed and remembered by Americans through the lens of a different artistic form of memory: the photograph.

At the beginning of the American Civil War’s Centennial in 1961, the famed writer Robert Penn Warren remarked that, “the Civil War is our only ‘felt’ history—history lived in the national imagination.” The painful memories and lived realities of fallen American soldiers in countless military conflicts beyond the Civil War—both historically and now—cast skepticism on Warren’s thesis, but the Civil War undoubtedly changed how nineteenth century Americans visualized their memories of the past. Previous conflicts in American history like the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 can only be visually remembered through the interpretive hands of painters, sculptors, and sketch artists. But the Civil War, thanks to the invention of the daguerreotype in 1839, has been absorbed and remembered by Americans through the lens of a different artistic form of memory: the photograph.

Photography depicted life in the camp and soldiers posing for “likenesses” in their finest blue and gray uniforms, but it also depicted horrific landscapes of death and the relentless destruction of war. Nineteenth century Americans were simultaneously horrified and fascinated by these scenes, and we today experience them in much the same way. In The Boy Solider, authors Alexandra Filipowski and Hugh T. Harrington parlay their own fascination with a now-famous photographic portrait of a sixteen-year-old Confederate soldier, Edwin Jemison, into a book about this young soldier’s life.

The Boy Soldier is a quick, straightforward read that covers the duration of Jemison’s short life from his birth in 1844 to his tragic death at the Battle of Malvern Hill at the tender age of seventeen. Lacking any primary source documents written in Jemison’s own hand, the authors rely instead on contemporary newspapers, census records, and military records of Jemison’s 2nd Louisiana regiment to interpret young Edwin’s life experiences. While many questions still remain about Jemison’s motives for joining the Confederate war effort, how he died, and even his correct burial location, Filipowski and Harrington do a respectable job of bringing life to Jemison’s stoic portrait.

The first chapter of The Boy Soldier explores Jemison’s Georgia birth and his upbringing in Monroe, Louisiana, where his father practiced law and became a prosperous landowner and slaveholder. The bulk of the narrative then follows Jemison’s Civil War experience. Readers learn about Jemison’s enlistment in the Pelican Grays, a company of troops based out of Ouachita Parish (Edwin was the company’s youngest soldier), their incorporation into the 2nd Louisiana regiment, intense fighting during the Peninsula Campaign, and Edwin’s eventual death by artillery shell at Malvern Hill. The remaining two chapters offer speculations about Jemison’s final moments alive and his resting place. Regarding the latter, the authors convincingly show that even though a marker exists for Jemison at his family’s burial plot at Memory Hill Cemetery in Milledgeville, Georgia, young Edwin is most likely still buried alongside his comrades at Malvern Hill.

The Boy Soldier offers a sympathetic portrait of one soldier’s Civil War experience that is readable and educational, but more context about the world in which Jemison encountered would have further enhanced the narrative. For example, while readers briefly learn of the Jemison family’s Southern plantation lifestyle in the first chapter, little effort is made to connect this lifestyle to the messy antebellum political situation of the 1850s, or Louisiana’s eventual decision to secede from the Union after Lincoln’s election. Additionally, in the opinion of this reviewer, it would have been worthwhile for the authors to add an additional chapter or epilogue explaining the process by which they conducted their years-long research; a potential learning opportunity for Civil War history enthusiasts and genealogists alike seems to have been missed.

The Boy Soldier includes an array of images, maps, and an interesting postscript that chronicles the postwar lives of Jemison’s closest friends and family. The book will be particularly useful as a text for high school history teachers and college professors teaching survey-level U.S. history courses, especially when paired with another text that interprets the Civil War from a more holistic perspective. While not as comprehensive a study as some more experienced readers of Civil War history may expect, Filipowski and Harrington’s work on Edwin Jemison is worth reading by experts and beginners alike.

Nick Sacco is a public historian who currently works at the Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site in St. Louis.