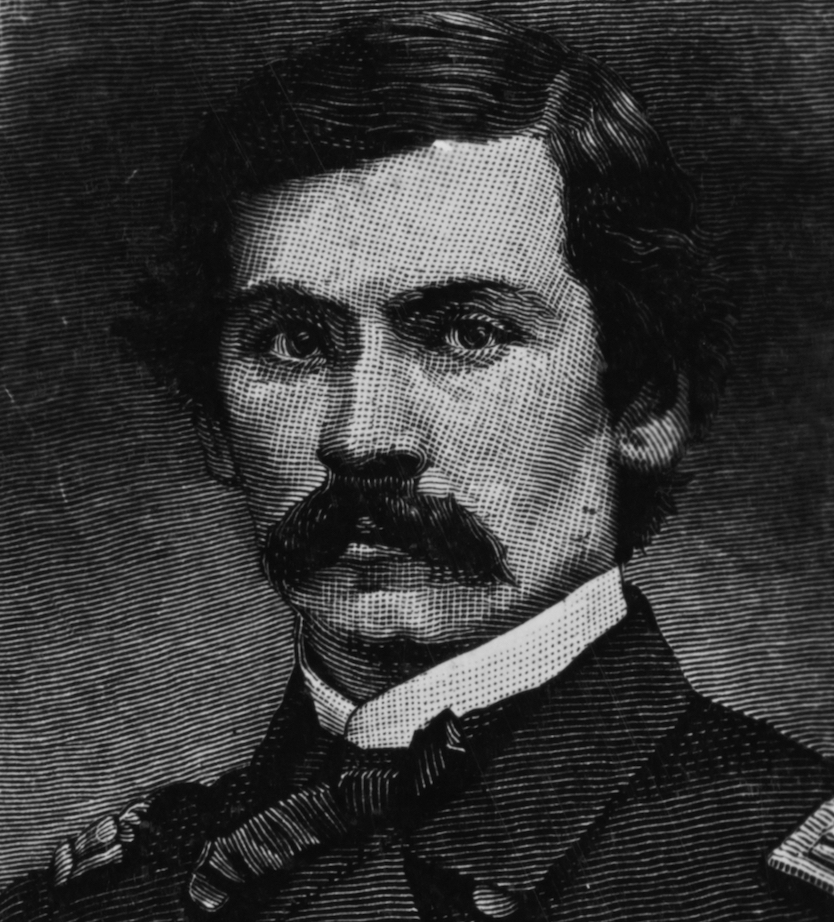

Lieutenant Samuel Dana Green

During the Battle of Hampton Roads on March 9, 1862—where the ironclad warships USS Monitor and CSS Virginia (Merrimac) fought to a draw—Lieutenant Samuel Dana Green was in the thick of the fight. The 23-year-old Maryland native served as Monitor‘s executive officer, and would temporarily take command of the vessel after its captain, John Worden, was wounded during the fight. Green wrote his parents with details of the groundbreaking struggle in a letter dated March 14, 1862, part of which follows below. Green remained in the navy for the remainder of the war, rising to the rank of lieutenant commander. He married twice, fathered three children, and died in 1884 at 45.

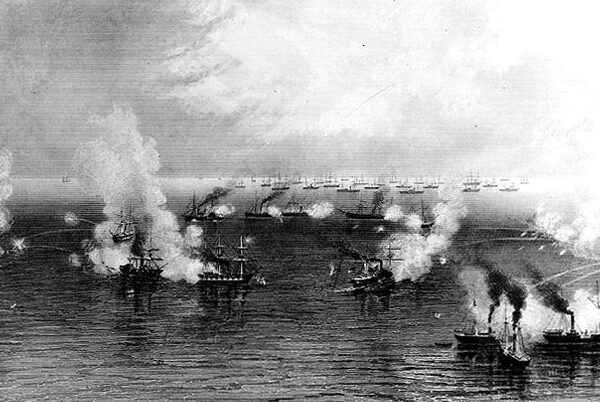

At 4 P.M. we passed Cape Henry and heard heavy firing in the direction of Fortress Monroe. As we approached it increased, and we immediately cleated ship for action. When about half way between Fortress Monroe and Cape Henry, we spoke a pilot boat. He told us the Cumberland was sunk and the Congress was on fire and had surrendered to the Merrimac. We did not credit it, at first, but as we approached Hampton Roads, we could see the fine old Congress burning brightly, and we knew then it must be so.

Badly indeed did we feel, to think those two fine old vessels had gone to their last homes, with so many of their brave crews. Our hearts were very full and we vowed vengeance on the “Merrimac,” if it should ever be our lot to fall in with her. At 9 P.M. we anchored near the Frigate Roanoke, the flag ship…. Captain Worden immediately went on board, and received orders to proceed to New Port News, and protect the Minnesota (which was aground) from the Merrimac. We immediately got underweigh and arrived at the Minnesota at 11 P.M. I went all board in our cutter and asked the Captain what his prospects were of getting off. He said he should try to get afloat at 2 A. M. when it was high water.

I asked him if we could render him any assistance, to which he replied No. I then told him we should do all in our power to protect him from the attacks of the Merrimac. He thanked me kindly and wished us success. Just as I arrived back to the Monitor, the Congress blew up, and certainly a grander sight was never seen, but it went straight to the marrow of our bones. Not a word was said, but deep did each man think, and wish he was by the side of the Merrimac. At 1 A.M. we anchored near the Minnesota. The Captain and myself remained on deck, waiting for the Merrimac. At 3 A.M. we thought the Minnesota was afloat and coming down on us, so we got underweigh as soon as possible and stood out of the Channel. After backing and filling about for an hour we found we were mistaken and anchored again. At day light we discovered the Merrimac at anchor with several vessels under Sewall’s Point. We immediately made every preparation for battle.

At 8 A.M. on Sunday the Merrimac got underweigh, accompanied by several Steamers, and started direct for the Minnesota. When a mile distant she fired two guns at the Minnesota. By this time our anchor was up, the men at quarters, the guns loaded, and everything ready for action. As the Merrimac came closer, the Captain passed the word to commence firing. I triced up the port, run the gun out, and fired the first gun, and thus commenced the great battle between the “Monitor” and the “Merrimac.”

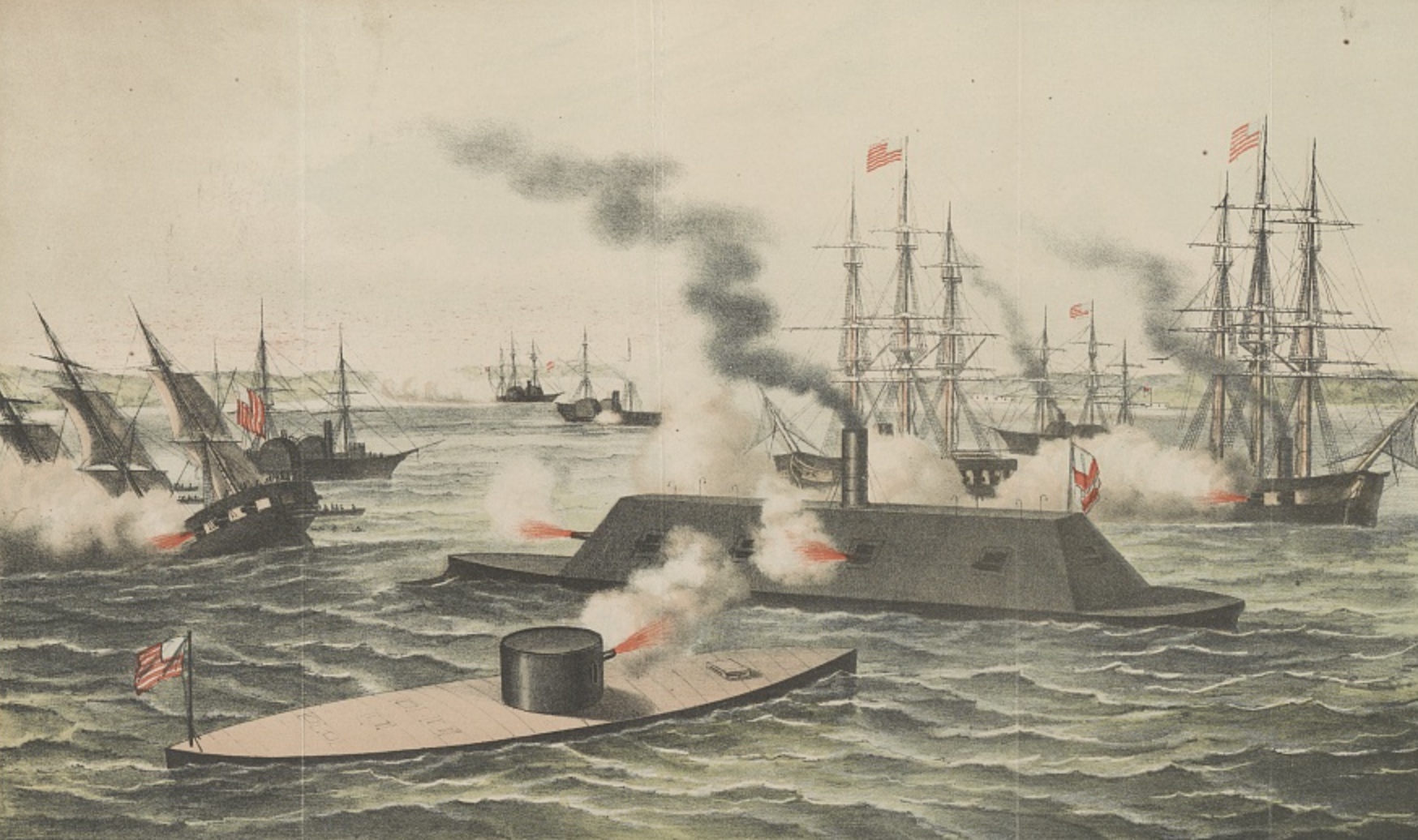

Kurz & Allison’s chromolithograph, “Battle between the Monitor and Merrimac”

Now mark the condition our men and officers were in. Since Friday morning, 48 hours, they had had no rest, and very little food, as we could not conveniently cook. They had been hard at work all night, and nothing to eat for breakfast except hard bread, and were thoroughly worn out. As for myself, I had not slept a wink for 51 hours, and had been on my feet almost constantly. But after the first gun was fired, we forgot all fatigues, hard work and every thing else, and went to work fighting as hard as men ever fought. We loaded and fired as fast as we could. I pointed and fired the guns myself. Every shot I would ask the Captain the effect, and the majority of them were encouraging. The Captain was in the Pilot House directing the movements of the vessel. Acting Master Stodder was stationed at the wheel which turns the Tower, but as he could not manage it, he was relieved by Stimers.

The speaking trumpet from the Tower to the pilot House was broken, so we passed the word from the Captain to myself on the berth deck, by Pay Master Keeler and Captain’s Clerk Toffey. Five times during the engagement we touched each other, and each time I fired a gun at her, and I will vouche the 168 lbs. penetrated her sides. Once she tried to run us down with her iron prow, but did no damage whatever. After fighting for two hours, we hauled off for half an hour to hoist shot in the Tower. At it we went again as hard as we could. The Shot, Shell, grape, canister, musket and rifle balls flew about us in every direction but did us no damage. Our Tower was struck several times, and though the noise was pretty loud, it did not effect us any.

Stodder and one of the men were carelessly leaning against the Tower, when a shot struck the Tower exactly opposite to them, and disabled them for an hour or two. At about 11:30 the Captain sent for me. I went forward, and there stood as noble a man as lives, at the foot of the ladder of the pilot house. His face was perfectly black with powder and iron, and he was apparently perfectly blind. I asked him what was the matter. He said a shot had struck the Pilot House exactly opposite his eyes and blinded him, and he thought the Pilot House was damaged. He told me to take charge of the ship and use my own descretion. I lead him to his room and laid him on the sofa, and then took his position.

On examining the Pilot house I found the iron hatch on top, had been knocked about half way off, and the second iron log from the Top, on the forward side was completely cracked through. We still continued firing, the Tower being under the direction of Stimers. We were between two fires. The Minnesota on one side and the Merrimac on the other. The latter was retreating to Sewell’s Point and the Minnesota had struck us twice on the Tower. I knew if another shot should strike our pilot house in the same place, our steering apparatus would be disabled and we should be at the mercy of the Batteries on Sewall’s Point. The Merrimac was retreating towards the latter place.

We had strict orders to act on the defensive and protect the Minnesota. We had evidently finished the Merrimac as far as the Minnesota was concerned, our pilot house was damaged and we had strict orders, not to follow the Merrimac up; therefore, after the Merrimac had retreated, I went to the Minnesota and remained by her until she was afloat. Genl. Wool and Secretary Fox both have complimented me very highly for acting as I did, and said it was the strict military plan to follow. This is the reason we did not sink the Merrimac, and everyone here capable of judging says we acted exactly right.

Henry Bill’s 1862 lithograph “The First Battle Between “Iron” Ships of War”

The fight was over now and we were victorious. My men and myself were perfectly black with smoke and powder. All my under clothes were perfectly black and my person was in the same condition. As we ran along side the Minnesota, Secretary Fox hailed us, and told us we had fought the greatest Naval battle on record and behaved as gallantly as men could. He saw the whole fight. I felt proud and happy then mother, and felt fully repaid for all I had suffered. When our noble Captain heard the Merrimac had retreated he said he was perfectly happy and willing to die, since he had saved the Minnesota. Oh how I love and venerate that man. Most fortunately for him his class mate and most intimate friend, Lieut. Wise saw the fight and was along side immediately after the engagement. He took him on board the Baltimore boat and carried him to Washington that night.

The Minnesota was still aground and we stood by her until she floated about 4 P.M. She grounded again shortly and we anchored for the night. I was now Captain and 1st Lieutenant and had not a soul to help me in the ship as Stodder was injured and Webber useless. I had been up so long, had had so little rest and been under such a state of excitement that my nervous system was completely run down. Every bone in my body ached. My limbs and joints were so sore that I could not stand. My nerves and muscles twitched as though electric shocks were continually passing through them and my head ached as if it would burst. Some times I thought my brain would come right out over my eye brows.

I laid down and tried to sleep, but I might as well have tried to fly…. But no sleep did I get that night, owing to my excitement. The next morning at 8 o’clock we got underweigh, and stood through our fleet. Cheer after cheer went up from the Frigates and small craft for the glorious little Monitor and happy indeed did we all feel. I was Captain then of the vessel that had saved New Port News, Hampton Roads, Fortress Monroe (as Genl. Wool himself said) and perhaps your Northern Ports. I am unable to express the happiness and joy I felt, to think I had served my country and Flag so well, at such an important time….

Source

For Green’s full letter, visit: www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/e/eye-witness-account-of-the-battle-between-the-u-s-s-monitor-and-the-c-s-s-virginia-mar-9-1862.html

Related topics: naval warfare