In the Voices section of the Winter 2021 issue of The Civil War Monitor we highlighted quotes by Union and Confederate soldiers about the war’s grisly toll. Unfortunately, we didn’t have room to include all that we found. Below are those that just missed the cut.

“While bathing the face of a man in the agonies of death, I chanced to look round, and there by my side were thirty or forty corpses that had been brought on board, rolled in the blood-stained blankets in which they had been carried from the field, and wearing every expression by which the human face is distorted. I had always heard that persons dying of gun-shot wounds preserved a happy expression, but on those ghastly faces was fixed anger, revenge, suffering, and one man, with a demoniac stare in his eyes, had his right hand raised and clenched, as if to defy death itself. Of all who lay there I saw but one who seemed to have died in peace: a young boy of about seventeen, with light hair, beautiful features, and a heavenly expression, as if he had been translated far from that scene of woe and suffering. As I looked in his large blue eyes that no kind hand had closed, I thought of the distress awaiting those to whom he was dear and, stooping down to brush his hair aside, could not restrain the tear which fell on his white face, seeming to mar its placid purity so much that I hastily wiped it off, feeling as though he had silently reproached me for my sorrowing. Among the sufferers was a son of General Pillow, who received neither more nor less attention than any one else; all lay crowded together, dead and dying, friends and enemies—civil war in all its hideousness! I wished that the picture could have been daguerreotyped on the brains of those who let us drift into it—it would have been punishment enough, even for them.”

—Northern civilian Margaret Sumner McLean, on witnessing some of the casualties at the Battle of Belmont, Missouri, in her diary, November 1861. McLean was a passenger on a steamer forced to stop in Belmont after coming under fire; the vessel took on dead and wounded troops soon after.

“The first thing I noticed on coming into the road was the dead body of a mere boy, not more than fifteen years old, lying with his face half buried in a pool of mud. His arms were outstretched, and his right hand grasped the barrel of an old rifle that lay beside him. In passing the body I noted with a shudder that some of the horses had trampled on the skull. Over a fence, just behind the boy, lay an old man, he also clinging to his rifle. Both were clad in the merest rags, and the old man’s hat still partly covered his head. They had evidently fallen at the same time—the boy just after clearing the fence, the old man in the act of climbing.”

—John A.B. Williams, 15th Pennsylvania Cavalry, on a scene he witnessed during the Battle of Stones River, in his memoirs

“A piece of shell tore a limb from his body, and the wretched man dropped to the ground bathed in his own life’s blood. His hair was snowy white, and the hot crimson tide covered his pale face, giving him a ghastly look.”

—James H. Clark, 115th New York Infantry, on the death of Colonel Dixon Stansbury Miles at Harpers Ferry on September 16, 1862, in his postwar account of the war

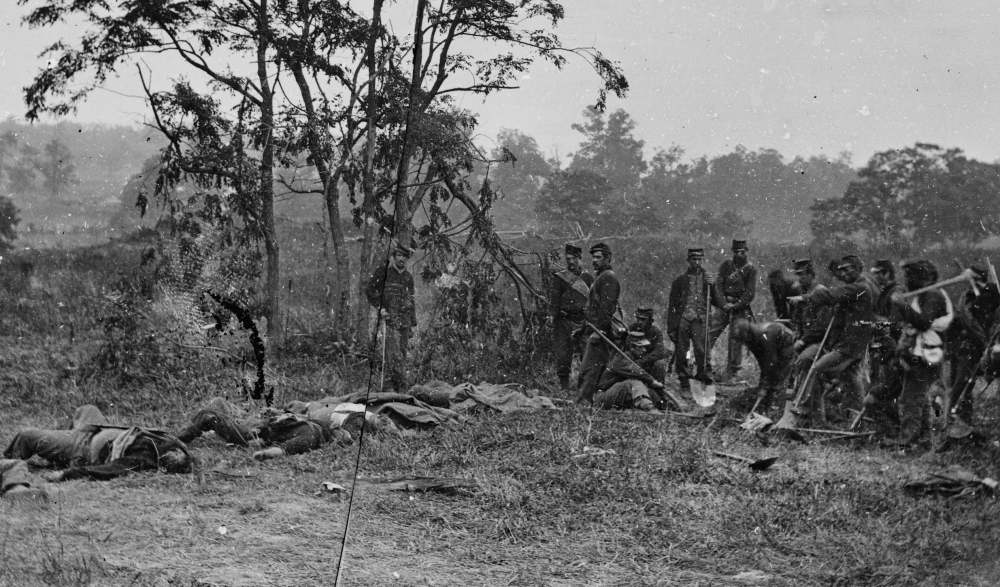

A Union burial party digs graves for dead soldiers on the Antietam battlefield.

“This afternoon, there has been a flag of truce; during which they have buried dead, and even removed wounded men, who have lain on the field since Sunday! It is now Wednesday. Company D has assisted in burying a hundred and fourteen corpses. I have just seen Cyrus Stowell, who tells me a terrible story. The decomposition of the bodies was so advanced, that the flesh slipped from the arms as our men tried to raise them, the heads fell away from the trunks sometimes, and the worms crawled from the dead upon the hands of the living! Unspeakably dreadful!”

—James Kendall Hosmer, 52nd Massachusetts Infantry, on a scene he witnessed during a break in the fighting at Port Hudson, Louisiana, in his diary, June 17, 1863

“I then procured a horse and orderly to visit the hospitals and learn the number each contained. To do this it was necessary to pass near the battle-field, the odor from which was insufferable. For over a mile, the ground was thickly strewn with unburied men, mules, and horses, whose decomposing bodies infected the atmosphere for miles.”

—Union army surgeon Thomas T. Ellis, on a scene he encountered during the Peninsula Campaign, in his diary

“In clearing up the battlefields … only shallow graves could be dug for the dead, owing to the large amount of water in the soil, which would fill them at the depth of a shovel, therefore the bodies were laid in rows, sometimes in heaps, and the earth thrown over them. Some did not have even such a burial as this…. The sight then was sickening, many bodies lay as they fell, and struggling, died. Some were covered with earth, but generally only a few shovelfuls were thrown on their bodies, the arms and legs being exposed, and some were covered with sticks of wood from a pile there was in the woods. A large number of horses that had been killed were also carelessly buried, or left uncovered in the same manner. The air we breathed was putrid, and the water we drank seemed tainted with the foul drainings of the battlefield.”

—Union officer James H. Rickard on the aftermath of the fighting at Fair Oaks, in his memoirs

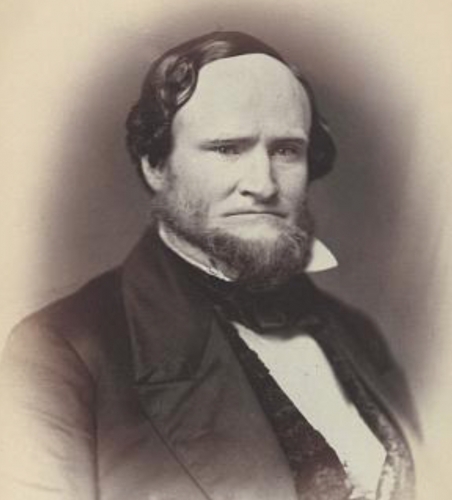

William Barksdale

“I saw his body soon after the life had left it, next morning, and, having seen him on the floor of Congress, recognized it at once. He was dressed in a suit of the light-bluish-gray mixture of cotton and wool, …. [h]is vest thrown open disclosed a ball hole through the breast, and his legs were bandaged and bloody from gunshots through both of them…. There he lay alone, without a comrade to brush the flies from his corpse.”

—George Grenville Benedict, 12th Vermont Infantry, on viewing the body of Confederate general William Barksdale on the Gettysburg battlefield, in a letter to his hometown newspaper, July 4, 1863

“Squads from both armies were sent out, and for at least two hours the work of burying the dead went on. The dead were buried by simply throwing earth onto the bodies where they had fallen. I walked out onto the battle grounds and observed the victims lying scattered over the field as far as the sight could reach. The bodies were bloated and swollen to the stature of giants. I saw some few men ripping open the pockets of the dead with their jackknives and taking therefrom watches, money and other valuable things, reeking with putrifaction, and transferring them to their own pockets. I picked up a photograph or tintype of a woman and two children which some soldier had lost, and I also found a splendid Springfield rifle which I appropriated and carried to camp.”

—J.J. Kellogg, 113th Illinois Infantry, on a pause in the fighting at Vicksburg to bury the dead, in his diary, May 25, 1863

“There, among the branches of the fallen oak, sits leaning against the trunk of the tree the horrible corpse of a man who died by slow tortures. Here he fell. Here are his rifle and accoutrements, and a little pool of blood dried into the grass, making the green blades dead and yellow as usual. I can see, by the trace of blood, the places where the poor man rested, dragging himself toward the tree top. A piece of shell hit him in the knee. He bound his handkerchief as tight as he could around the limb above the wound, to stop the flow of blood. The weeds and grass near him show his struggles to get shelter from the sun. He managed to break off two or three little boughs, having dead leaves, and arrange them together so as to give him some semblance of shade, but the scorching heat followed him, and thirst was more terrible than the heat. He tried to suck the juice from the roots of a few rank weeds which he could reach and get out of the ground with his fingers. These roots lie near him, still having the marks of his teeth; some of them are of the kinds likely to have increased his thirst. There are indications that he tried to slake the fire of thirst with his own blood. His strength failed so that he could not creep back to his friends; but the difference of decomposition as seen in him and in the man who was killed instantly, shows that his agonies must have lasted at least two days after the assault. His head is leaned back, the sun shining in his blackened face, and his lower jaw has fallen. His vest, his fine linen shirt and neckcloth, indicate that the young man was probably one of the many students who left college to serve his country, but all his agonies were to gratify the idiotic caprice of a sot in brigadier’s uniform. His death was but one of the many deaths that were to encourage the enemy to hold out till the last. I hasten away, fearing to breathe longer the infected air.”

—Edward Bacon, 6th Michigan Infantry, on a scene he encountered during the struggle for Port Hudson, in his memoirs

“Released prisoners say that a pestilence is feared in Richmond, where almost every house is turned into a hospital. If a man dies of fever his body is rolled in tar and smoked before burial. Corpses are buried without coffins and scarcely covered with earth. No names mark the grave, but simply the number which that one grave contains: ‘Sixty-five Confederates,’ ‘Twenty Federals,’ or ‘Yankees,’ etc.”

—Union surgeon John Gardner Perry in a letter home from Virginia, July 25, 1862

“[A] number of our wounded soldiers were still being brought in from the battle-field, a distance of ten miles. The sight of these sufferers was touching. Some were in ambulances, while others lay in the bottoms of ordinary farm wagons, with little or no shelter from the hot sun. Their wounds had been dressed, and the heroic courage which they manifested was something inspiring to witness. Many bodies of the dead had been sent in for transportation. In a wheel wright shop to which my attention was attracted, I saw the lifeless forms of two officers in uniform—a major and a lieutenant—awaiting boxing. The faces were ghastly, and I turned from them with a feeling of pain as I thought of the hearts that even now, perhaps, were being torn with grief in the distant homes. These sights were realities, not pictures, and gave me a more vivid idea of the horrors of war than the most graphic pen descriptions I had ever read. Alas! I thought, to what extent is this slaughter to go on, and when will the sacrifice for patriotism’s sake be complete?”

—Pennsylvania militiaman Louis Richards, on the scene in Hagerstown, Maryland, in the wake of the Battle of Antietam, in his diary, September 19, 1862

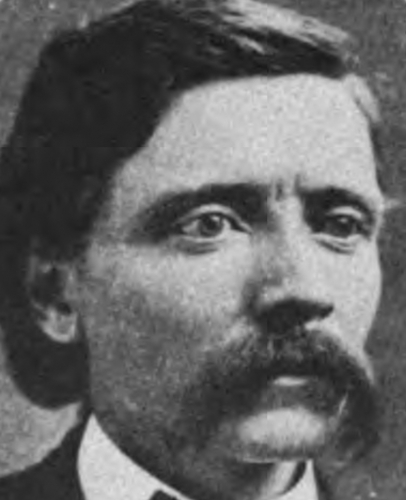

W.W. Heartsill

“The ground is again white with snow. A detail is made from each barrack; to go out to burry the dead, which have accumulated in the dead-house for the past thirteen days. A sight of the inside of this dead-house is of the most revolting and sickning character; that ever a man beheld. Scarcly a corpse but is mutilated, and that too, about the face; by rats and scores of cats that infest the building, scarcly any of the bodies can be recognized by their faces. The dead are decently intered in a plain coffin, and some of the graves are marked by friends, but in most cases their names are written with a pencil on a board, which will not remain legible long.”

—W.W. Heartsill, 2nd Regiment, Texas Mounted Rifles, in his diary, February 13, 1863

“Day before yesterday we marched over the battle ground that Jackson had his last fight on. All of our men had been buried, but the Yankees lay just as they were killed. I never saw such a scene before. I saw just from the road, as I did not go out of my way to see any more. It must have been nearly a thousand. Our wagon actually ran over the dead bodies in the road before they would throw them out, or go around them. The trees were literally shot all to pieces. The wounded Yankees were all over the woods, in squads of a dozen or more, under some shady tree without any guard of any kind to guard them. I recollect one squad on the side of the road with their bush shelter in ten steps of a dead Yankee, that had not been buried and was horribly mangled. I don’t suppose the dead Yankees of that fight will ever be buried. It will be an awful job to those who do it, if it is ever done.”

—North Carolina soldier Walter Lee, in a letter to his mother, September 5, 1862

“The dread reality of war was before us in this frightful death, upon the cold, hard stones. The mortal suffering, the fruitless struggle to send a parting message to the far-off home, and the final release by death, all enacted in the darkness, were felt even more deeply than if the scene had been relieved by the light of day. After a long interval of this horror, our stretcher bearers came, and the poor suffering heroes were carried back to houses and barns.”

—Rufus Dawes, 6th Wisconsin Infantry, on the aftermath of the Battle of South Mountain, in his memoirs

Sources

A Northern Woman in the Confederacy (1914); Leaves from a Trooper’s Diary (1869); The Iron Hearted Regiment (1865); The Color-Guard (1864); Army Life in Virginia (1895); Leaves from the Diary of an Army Surgeon(1863); The Memorial War Book (1894); War Experiences and the Story of the Vicksburg Campaign … (1913); Among the Cotton Thieves (1867); Letters from a Surgeon of the Civil War (1906); Eleven Days in the Militia During the War of the Rebellion (1883); Fourteen Hundred and 91 Days in the Confederate Army (1876); Forget-Me-Nots of the Civil War(1909); Service with the Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers (1890).