In the Voices section of the Fall 2020 issue of The Civil War Monitor we highlighted quotes by Union and Confederate soldiers about the extreme thirst they suffered while on campaign. Unfortunately, we didn’t have room to include all that we found. Below are those that didn’t make the cut. “Often while marching I drank water out of the mud of the road where the troops were treading, and was glad to get it. If chocolate had been made of most of the water we drank while marching in Virginia it would not have changed the color. I don’t remember that we ever examined water very closely if it was wet.” —Charles William Bardeen, a fifer in the 1st Massachusetts Volunteer Militia, in his memoirs “Then they discovered the enemy on three sides of them, with an almost impenetrable swamp on the other. This was Dover swamp, and as near as I can judge was similar to the one we went through on Roanoke island, only of greater extent. There was only one choice, and that must be quickly accepted. Into the swamp they plunged, with mud and water to their knees, and thick tangle brush and briars higher than their heads. They could go only in single file, and their progress was slow and tedious. Towards noon they were met by another enemy; the water in their canteens had given out and they began to experience an intolerable thirst. With a burning sun above them and scarcely a breath of air, with all manner of insects, reptiles and creeping things around them, their condition was indeed pitiable. Still they pressed forward, some of them filtering the slimy, muddy water through their caps or handkerchiefs and drinking it, but it served better as an emetic than for quenching thirst.” —David L. Day, 25th Massachusetts Infantry, on the trials of fellow Union soldiers while on campaign in North Carolina, in his diary, May 25, 1863

“Some of the wells dug by the Yanks furnish passable water, an improvement anyway on swamp water. Well water in great demand and sells readily for such trinkets as the men have to dispose of.”

—Andersonville prisoner Robert Ransom, in his diary, May 18, 1864 “These Virginia miles are very long to travel especially when one goes on foot…. I never was so thirsty before in my life and hope I never shall be again.” —Lewis Bissell, 19th Connecticut Infantry, on a recent march his regiment made during the Overland Campaign, in a letter to his father, June 4, 1864

“The field was covered all over with wounded men groaning and calling for water; some attempted to crawl on their bellies to the river side for a drop of water to relieve their thirst.” —Massachusetts soldier Warren Freeman, on a scene he witnessed days after the Battle of Fredericksburg, in a letter to his father, December 25, 1862 “We got under way down stream early in the morning and about ten o’clock our old shaky craft turned its nose up the muddy current of the Father of Waters. Every fellow that could get a string lowered his coffee can for a drink of water. The boys would smack their lips and say the dirt in it tasted like Wisconsin dirt.” — Chauncey Cook, 25th Wisconsin Infantry, on his regiment’s recent journey by transport boat on the Mississippi River, in a letter to his parents, August 3, 1863 “I cannot tell you how I felt that day. As long as there was any prospect of a fight I kept my place in the ranks, but when we gave up the chase and turned back to where our blankets were left, I fell out to get some water and bathe my head. My tongue was swollen with the heat and thirst, and I so faint I could hardly stand. I followed on, however, but the regiment was some distance ahead.” —Oliver Wilcox Norton, 83rd Pennsylvania Infantry, on his experiences on the day of the Battle of Hanover Court House, in a letter to his siblings, June 2, 1862 “I saw one wounded Federal lying under a little white oak bush out in the open field. I suppose he had been there for at least forty-eight hours. He was nearly perished with thirst and begged me for a drink of water. I did not have a drop and did not know where to get any. I did not see any farmhouse near nor far, and we were under marching orders, liable to move at any moment. I told him that water was scarce in his present neighborhood, but that was sad news, poor consolation, and poverty-stricken comfort to a man who is dying for water. It was enough to cruelly crush his last hope. I told him that the Citizens’ Committee from Washington was on the field and I would tell the first man I met where to find him, and he would administer to his pressing wants. The poor wounded man exclaimed: ‘Oh, I have heard that for the last twenty-four hours, and they have not found me yet.’ Ah, what a striking object lesson on the horrors and probable vicissitudes of cruel war! One moment a strong robust man may be wielding the saber or bayonet like a Hercules and the next instant he may be lying on the field as helpless as a babe and begging his antagonist for a drink of water.” —Confederate artillerist George Michael Neese, on encountering a wounded Union soldier while walking the field of the recently fought Battle of Second Manassas, in his diary, September 1, 1862

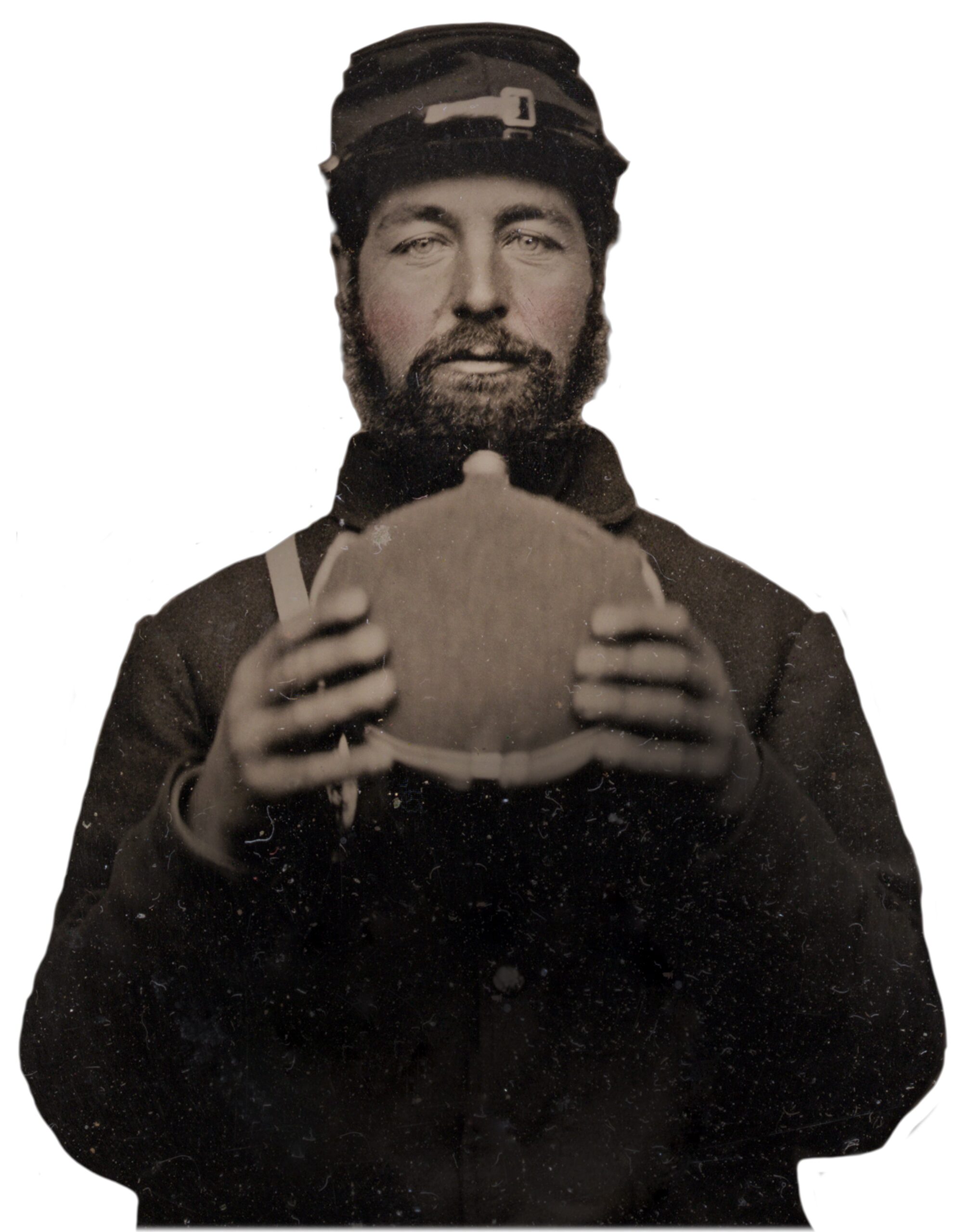

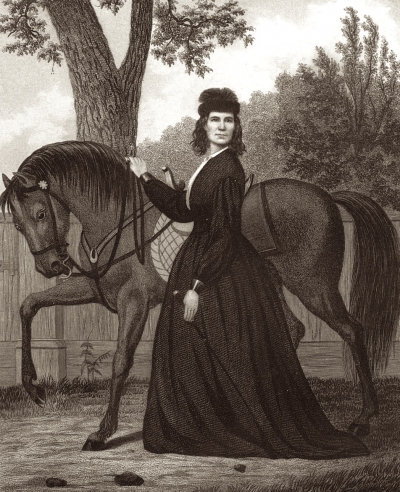

Sarah Emma Edmonds

“The village of Centerville was not yet occupied by the rebels, so that I might have made my escape without any further trouble; but how could I go and leave those hospitals full of dying men, without a soul to give them a drink of water? I must go into that Stone Church once more, even at the risk of being taken prisoner. I did so—and the cry of ‘Water,’ ‘water,’ was heard above the groans of the dying.” —Nurse Sarah Emma Edmonds, on returning to a field hospital near the battlefield at First Bull Run, as the Union army retreated, in her memoirs “The men fought well, however, though half dead with heat, thirst, and weariness. Some broke for the river and plunged in the cool water for an instant, then emerging, rushed back to the fray and fought like lions.” —Union surgeon Thomas T. Ellis, on the performance of Union troops at the Battle of White Oak Swamp, in his diary, June 1862 “The water we have to drink is hot, hot. Oh! what would I give for a good drink of water. Oh! for deliverance from this vessel of misery.” —Confederate POW James Robert McMichael, on being transferred by ship from Fort Delaware to Morris Island, South Carolina, in his diary, August 25, 1864 “In the summer of 1864, the problem of water-getting before Petersburg was quite a serious one for man and beast…. The soldiers … would scoop out small holes in old water courses, and patiently await a dipperfull of a warm, milky-colored fluid to ooze from the clay, drop by drop. Hundreds wandered through the woods and valleys with their empty canteens, barely finding water enough to quench thirst. Even places usually dank and marshy became dry and baked under the continuous drought. But such a state of affairs was not to be endured a great while by live, energetic Union soldiers; and as the heavens continued to withhold the much needed supply of water, shovels and pickaxes were forthwith diverted from the warlike occupation of intrenching to the more peaceful pursuit of well-digging, it soon being ascertained that an abundance of excellent water was to be had ten or twelve feet below the surface of the ground. These wells were most of them dug broadest at the top and with shelving sides, to prevent them from caving, stoning a well being obviously out of the question. Old-fashioned well-curbs and sweeps were then erected over them, and man and beast were provided with excellent water in camp.” —Massachusetts artillerist John Billings, in his memoirs