Hard Tack and Coffee

Hard Tack and CoffeeSleeping Civil War soldier

In the Voices section of the Spring 2021 issue of The Civil War Monitor we highlighted quotes by Union and Confederate soldiers about shirking. Unfortunately, we didn’t have room to include all that we found. Below are those that didn’t make the cut.

“The soldier who unmurmuringly meets and performs his dutiers of hardship and danger must be provided with something of that divine armor which fits him to be a soldier of the cross. The man who says he loves to face the ‘leaden rain and iron hail’ of battle is either a liar or a monstrosity. No man who cares for life and friends can go into battle without a natural shudder and dread. The wonder is that duty and pride are strong enough in any man to urge him forward into the very teeth of death. Let us be charitable as possible toward the white-livered wretches who fall out of the ranks at the first bidding of the cannon’s voice.”

—Zenas T. Haines, 44th Massachusetts Volunteer Militia, in a letter home, January 2, 1863

“I must leave him for the present to direct attention to the other class of men of whom I wish to say something. These were the beats of the service—a name given them by their comrades-in-arms. There were all grades of beats. The original idea of beat was that of a lazy man or a shirk, who would by hook or by crook get rid of all military or fatigue duty that he could; but the term grew to have a broader significance.

One of the milder forms of beat was the man who sat over the fire in the tent piling on wood all the time, and roasting out the rest of the tent’s crew, who seemed to have no rights that this fireman felt bound to respect. He was always cold. He wore overcoat, dress-coat, blouse, and flannels the full government allowance all at once, but never complained of being too warm. He never took off any of these garments night or day unless compelled to on inspection. He was most at home on fatigue duty, for he seemed fatigued from the start and moved like real estate. A sprinkling of this class seemed necessary to the success of the Union arms, for they were certainly to be found in every organization.

Another and more positive type of beat were the men who never had any water in their canteens. Even when the army was in settled camp, water was not always to be had without going some distance for it; but these men were never known to go after any. They always managed to hang their canteen on some one else who was bound for the spring. If, when the army was on the move, a rush was made during a temporary halt, for a spring or stream some distance away, these men never rushed. They were satisfied to lie down and drink a supply which they took their chances of begging, from some recruit, perhaps, who did not know their propensities. If it happened to any man to be so straitened in his cooking operations as to be under the necessity of borrowing from one of these, he was sure of being called upon to requite the favor fully as many times as his temper would endure it.”

—John D. Billings, 10th Massachusetts Light Artillery, in his memoirs

“A number of soldiers were summarily punished to-day for shirking camp duty. There are about forty men in camp, at a rough estimate, for whom severity in punishment for offences is the only remedy. They seem to have been hardened at home to that kind of treatment.”

—John C. Myers, 192nd Pennsylvania Infantry, in his diary, August 30, 1864

“So soon as it was ascertained that a colonel had been made a prisoner, I was ordered to be conducted to the headquarters of General Logan, he being the commander of the Fifteenth Army Corps, to which my captors belonged. I was so utterly exhausted with the heat and exertions of the day, as well as depressed with a deep feeling of chagrin and disappointment, that I could scarcely walk. I was also seized with a violent headache, and my guard kindly permitted me to rest in the shade by the side of a gurgling, vine-embowered spring, and bathe my throbbing temples in its cooling waters. He was a fine specimen of the soldier, and professed to be a Democrat and opposed to the war. As he carried me through the hundreds of shirks and stragglers in the rear of the line of battle, he expressed his contempt for such imbeciles in language more emphatic than chaste, and declared that he had served three years in the army, and had never visited the rear before in the hour of battle. He had a good face, and was doubtless a brave and true man, and I regret to believe that Mr. Lincoln has sacrificed many thousands of such during the last four years.”

—Colonel Daniel Robinson Hundley, 31st Alabama Infantry, on being captured at Big Shanty, Georgia, on June 15, 1864, in his memoirs

“Nearly all the prisoners we capture say they are done fighting and shamefully say, many of them, that if exchanged and put back in the ranks they will shirk rather than fight. It would mortify me very much if I thought any of our men that they captured would talk so.”

—Captain Charles W. Wills, 103rd Illinois Infantry, in his diary, June 6, 1864

“It is altogether a good thing for us that we are here in the city; as I said before, it is all owing to General Slocum. His firm and just rule is felt already throughout the corps; men who have shirked, and, to use an expressive word, ‘bummed’ all through the campaign, are getting snubbed now, while those who have done their duty quietly and faithfully are being noticed.”

—Lieutenant Colonel Charles Fessenden Morse, 2nd Massachusetts Infantry, in a letter home from Atlanta, September 18, 1864

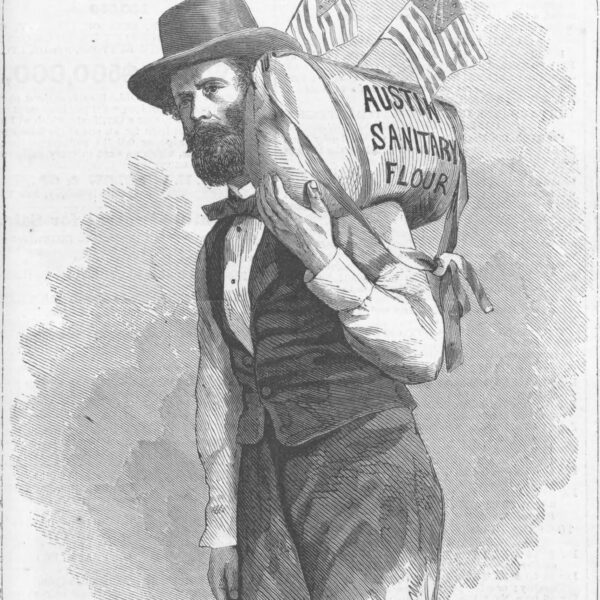

Hardtack and Coffee

Hardtack and CoffeeA soldier shirking duty

“An amusing incident occurred here: at the first shot fired by the rebels, as the ball whistled over our heads, a man in our company named —, who was detailed in the surgeon’s department, and on a march carried the box that contained our medical stores on his back, strapped on like a knapsack, at the first fire dropped on his knees behind a large tree, with his hands clasped in front of him, and his countenance showing every sign of terror. Now, this same fellow, in the seven days’ retreat, made himself scarce, apothecary shop and all, and we never saw any thing of him until about a month before our time expired. He had been hanging about hospitals and convalescent camps, and had joined us then to get an honorable discharge. This is only one of the many specimens of the curs that shirk duty and come to no punishment and receive government pay. There are thousands of them.”

—Alfred Davenport, 5th New York Infantry, in a letter home, June 1, 1862

“This hospital is divided into three departments…. In the third are more than 600 men, quartered under shelter tents. I am in this department. It is not supposed that there are any sick men here. They are all either dead beats or afflicted with laziness, and a draft is made from among them twice a week for the front. I had been here only four days when I was drawn, but Garland of company C, who is an attache at Doctor Sadler’s office, saw my name on the roll and scratched it off. Although there are none here supposed to be sick, there seems to be a singular fatality among them as we furnish about as large a quota every day for the little cemetery out here as they do from the sick hospital.”

—David L. Day, 25th Massachusetts Infantry, in his diary, July 20, 1864

“Some … men abandoned their colors early in the first day to pillage the captured encampments; others retired shamefully from the field on both days while the thunder of cannon and the roar and rattle of musketry told them that their brothers were being slaughtered by the fresh legions of the enemy.”

—Confederate general P.G.T. Beauregard in his official report on the Battle of Shiloh, April 1862

Sources

Letters from the Forty-Fourth Regiment M.V.M. (1863); Hardtack and Coffee (1888); A Daily Journal of the 192d Reg’t Penn’a Volunteers (1864); Prison Echoes of the Great Rebellion (1874); Army Life of an Illinois Soldier (1906); Letters Written During the Civil War, 1861–1865 (1898); Soldiers’ Letters, from Camp, Battle-field and Prison (1865); My Diary of Rambles with the 25th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry (1884); Bell Irvin Wiley, The Life of Johnny Reb: The Common Soldier of the Confederacy (1943).