In the Voices section of the Winter 2017 issue of The Civil War Monitor we highlighted first-person quotes by Union and Confederate soldiers about their recurring bouts of hunger. Unfortunately, we didn’t have room to include all that we found. Below are those that didn’t make the cut.

“I enjoy the tramping, the mud, the cold, and being tired, and everything mean there is about soldiering, except being hungry. That beats me to a fraction. If I could only go without eating three or four days at a time I would pass as a soldier, but bless me, missing a meal is worse than drawing a tooth.”

—Illinois soldier Charles Wright Wills, in his diary, March 1864

“I now realy enjoy a meal, that two short years ago I would have turned away from with loathing. We poor soldiers have experienced the truth of the old Latin saying that hunger is the best sauce….”

—Green Berry Samuels, 10th Virginia Infantry, in a letter to his wife, March 25, 1863

“Our houses were besieged by hungry soldiers and officers. They ate everything offered them with a greediness that fully sustained the truth of their statement, that their entire subsistence lately had been green corn, uncooked, and eaten directly from the stalk.”

—Frederick, Maryland, resident Lewis H. Steiner, on the arrival of Confederate troops in the town, in his diary, September 6, 1862

“It was not a little entertaining to see some of our boys, now in hot pursuit of half-frantic poultry and pigs, and then wildly beating the air in the vicinity of bee-hives which they had ruthlessly overturned in an irrepressible passion for stored sweets. The sight and taste of that white honey-comb will not soon pass from the memory of our jaded and hungry soldiers!”

—Zenas T. Haines, 44th Massachusetts Infantry, on an incident during his regiment’s time in North Carolina, November 11, 1862

“There is almost a mutiny this morning. No rations, and unless there should be better things before night, I shall not be surprised at any violence…. When I awoke … my fire was surrounded by men and officers clamoring for something to eat. They had some how got it into their heads that the hospital should be able to remove all the ills that flesh is heir to. I cooked what I had, and distributed till all was gone. Although hungry, I think I feel better to-night, than if I had permitted my mess chest to have remained locked by the key of selfishness.”

—Surgeon Alfred L. Castleman, 5th Wisconsin Infantry, in his diary, April 8, 1862. Castleman noted that the men of the regiment hadn’t “had a meal for three days.”

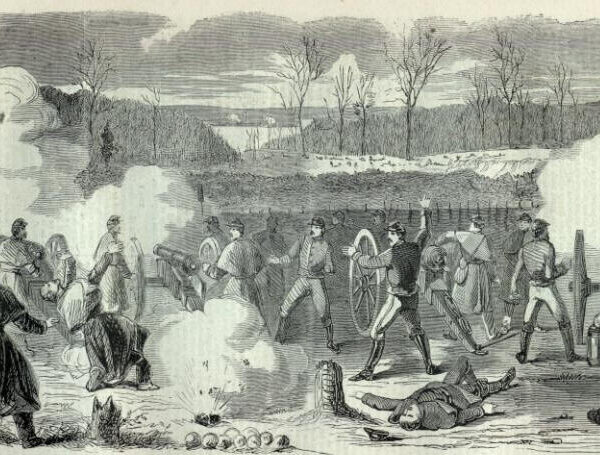

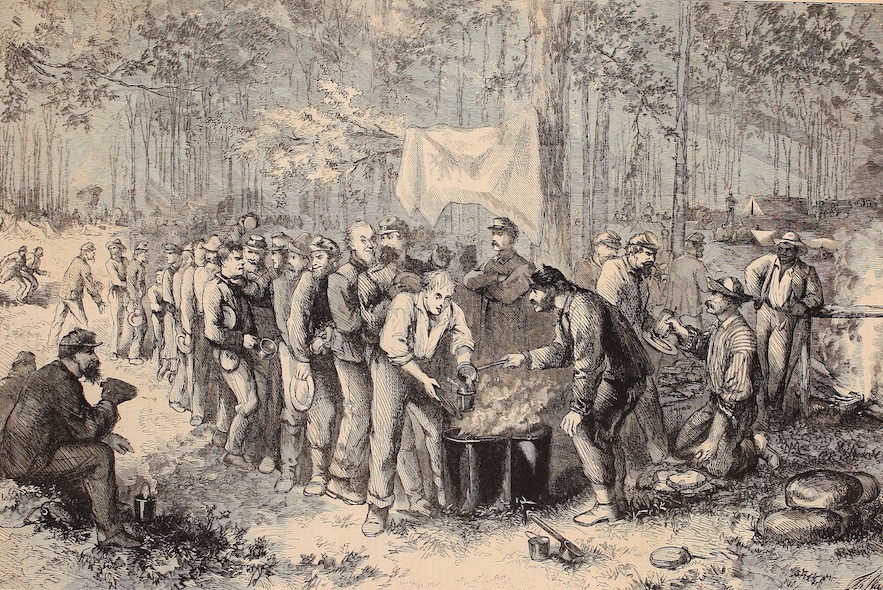

Hungry Union soldiers draw rations in this wartime sketch

“The fortifications are strong … and 25,000 men may defend the city against 100,000—provided we have subsistence. The great fear is famine. But hungry men will fight desperately. Let the besiegers beware of them!”

—Confederate War Department clerk John Beauchamp Jones, on the reported advance of the Army of the Potomac on Richmond, in his diary, March 10, 1863

“Some ladies visited the island to see us blue coats and laughed very much at our condition, thought it so comical and ludicrous the way the prisoners crowded the bank next the cook-house, looking over at the piles of bread, and compared us to wild men and hungry dogs. A chicken belonging to the lieutenant flew up on the bank and was snatched off in short order, and to pay for it we are not to receive a mouthful of food to-day, making five or six thousand suffer for one man catching a little chicken.”

—Andersonville prisoner Robert Ransom, in his diary, January 4, 1864

“[A]fter we had halted about a mile from town to feed and eat a snack, if we could get it, a good lady sent some of us, as a present, a dish of boiled and fried meat, Irish potatoes, cabbage, cornbread, biscuit, and, to cap the climax, a box of nice peaches. And I assure you … we were in a condition to appreciate and enjoy that treat, for … our rations had been out for the last four days.”

—Confederate cavalryman Richard Ramsey Hancock, on an incident that occurred as his regiment moved through La Grange, Tennessee, in his diary, September 4, 1862

“Four of our band decided to have what a soldier would call a good square meal. We proceeded to find a restaurant which was capable of filling the bill. After a short time we espied the sign ‘Donagana Restaurant.’ Mr. Rhoades, our leader, remarked that the name indicated a first-class establishment, which was, of course, not any too good for us. After a few moments of hurried consultation, we decided to invest in a breakfast, and we also decided that it should consist of fried pork, sausage, potatoes, and buckwheat cakes. In single file we marched into the restaurant and circled around one of the tables. The party consisted of R. G. Rhoades, Chas. Chamberlain, Wm. Wagner, and myself. We took our seats and patiently waited until a waiter should come and take our order. After a few moments a darky came to our table, and the order was given for pork sausage, fried potatoes, and buckwheat cakes for four. The sausages were served on a large platter, and the potatoes and buckwheat cakes in two deep dishes. In less time than it takes me to write it the dishes were empty, and the darky dropped a card in the middle of the table marked ‘$8.00.’ Each one of us looked at the other with consternation depicted on our countenances; but Rhoades, not dismayed, ordered the plates refilled, which was soon done. The darky picked up the eight-dollar card and in its place dropped one for fifteen dollars. That broke the camel’s back, but not our appetites. We got up from that table with a hungry stomach and a much lighter pocket-book, and I for one shall always keep that name in remembrance, — ‘Donagana Restaurant.’”

—Drummer boy William Bircher, 2nd Minnesota Infantry, in his diary, January 12, 1864

“[A] pretty good show for hungry men.”

Union general Hiram G. Berry

—Union general Hiram G. Berry, noting that his troops had just occupied a Confederate camp near Fairfax Court House, Virginia, taking “200 barrels of flour, bacon, sugar, tea, etc.,” in a letter home, July 18, 1861

“The boys eat as much as they please and put as much as they please in their pockets; they pick it up as children gather shells on the shore, for several reasons, first, ravenous hunger; second, as a medicine for urinary difficulties; third it will make a fire.”

—Union prisoner John Worrell Northrop, on his fellow POWs eating resin at a depot in Kingsville, South Carolina, during their transfer through the state, in his diary, September 14, 1864. Northrop noted that the resin had “waited so long for the blockade that the barrels have burst and scattered it as free as water.”

“It is a strange provision of nature that when one is very hungry the longing for a promised morsel assumes such proportions that it seems for a time to take possession of the whole of one’s being. I am quite certain that on this march each man in the regiment was so completely absorbed in his disappointment that for many miles it was to him the only source of discomfort.”

—Union surgeon John Gardner Perry, on his regiment receiving orders to march at daylight on Thanksgiving Day, thereby thwarting their plans for a holiday meal in camp, in a letter home, December 3, 1863

“The crops of corn are magnificent and are almost matured, but wherever our army goes, roasting ears and green apples suffer. I have often read of how armies are disposed to pillage and plunder, but could never conceive of it before. Whenever we stop for twenty-four hours every corn field and orchard within two or three miles is completely stripped. The troops not only rob the fields, but they go to the houses and insist on being fed, until they eat up everything about a man’s premises which can be eaten. Most of them pay for what they get at the houses, and are charged exorbitant prices, but a hungry soldier will give all he has for something to eat, and will then steal when hunger again harasses him. When in health and tormented by hunger he thinks of little else besides home and something to eat. He does not seem to dread the fatiguing marches and arduous duties.”

—Confederate surgeon Spencer Welch, in a letter to his wife, August 18, 1862

Union general Alexander Hays

“I have an appetite like a shark. For breakfast I took Boston crackers, broiled mackerel, coffee and cream, and cream without coffee.”

—Union general Alexander Hays, in a letter to his wife, December 3, 1863

“The life of a soldier in the field is no picnic. We can stand most anything but hunger.”

—Charles H. Lynch, 18th Connecticut Infantry, in his diary, May 30, 1864

“We get up very late, and hungry; oh! how hungry we are, we are all supplied with a liberal breakfast composed entirely of river water, and of course cannot complain. At 12 o’clk we receive the same for dinner that we got for breakfast, which is a very extravagant bill of fare.”

—Confederate soldier William Williston Heartsill, in his diary, January 12, 1863

Sources: Army Life of an Illinois Soldier (1906); A Civil War Marriage in Virginia (1956); Report of Lewis H. Steiner, M.D., Inspector of the Sanitary Commission … (1862); Letters from the Forty-fourth Regiment M.V.M. (1863); The Army of the Potomac, Behind the Scenes (1863); A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary Vol. 1 (1866); Andersonville Diary (1881); Hancock’s Diary (1887); A Drummer-Boy’s Diary (1889); Major-General Hiram G. Berry (1899); Chronicles from the Diary of a War Prisoner … (1904); Letters from a Surgeon of the Civil War (1906); A Confederate Surgeon’s Letters to his Wife (1911); Life and Letters of Alexander Hays (1919); The Civil War Diary, 1862–1865, of Charles H. Lynch (1915); Fourteen Hundred and 91 Days in the Confederate Army (1876).