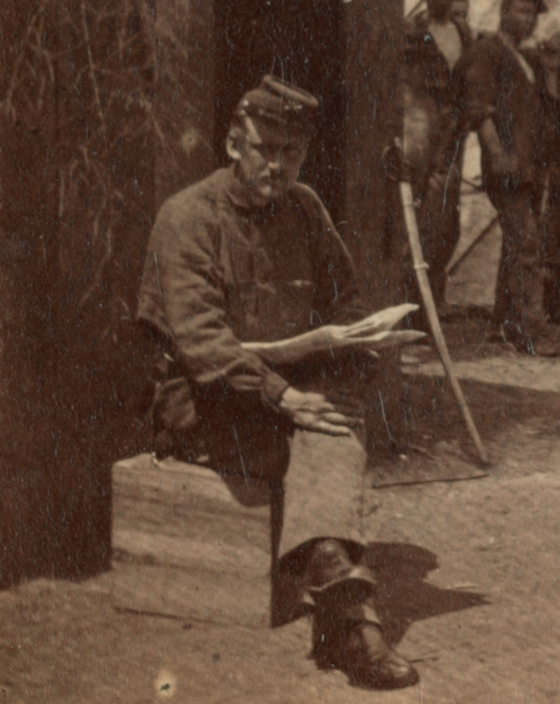

A Union soldier holds reading material in camp

In the Voices section of the Spring 2019 issue of The Civil War Monitor we highlighted first-person quotes about the quest for reading materials among Union and Confederate troops. Unfortunately, we didn’t have room to include all that we found. Below are those that didn’t make the cut.

“[A] man hungry for something to read will do as a man hungry for something to eat; if he can not get good he will take bad.”

—Captain Daniel Wait Howe, 79th Indiana Infantry, in his diary, March 4, 1864

“I never witnessed more delight manifested than by these men in obtaining periodicals with which they had been familiar in their far-distant homes.”

—United States Christian Commission member Melinda Rankin, on the reaction of Union soldiers to receiving the free books and newspapers she distributed to them

“Some are perusing old Waverlys, and others amusing themselves with Harper’s cuts, one has a volume of Shakespeare with his mind following intently the dramatic play of Edward the ‘three times.’”

—Daniel Ambrose, 7th Illinois Infantry, on a scene he observed while the regiment was in winter camp, February 16, 1863

“Our camps were flooded with a class of miserable, worthless literature in the shape of novels, which were sold by the thousand, for the sole purpose of making money. Men who were compelled to endure the monotonous camp-life of the army longed for some means by which their hungry appetites for reading could be satisfied. To supply this want, they were offered the chance of paying one dollar for three worthless novelettes, which contained a love story, or some daring adventure by sea or land. Thousands of these light and chaffy publications were sent to the camps, through the news agents; and the minds of the men were so poisoned that they almost scorned the idea of reading a book or journal which contained matter that would benefit their minds.”

—Asbury L. Kerwood, 57th Indiana Infantry, in his memoirs

“I have joined the ‘Fay Literary Institute,’ a sort of Lyceum. We have a library of about 500 or 600 volumes of good reading, so I can read when I have nothing else to do. It is very pleasant, all the boys in my section belong.”

—Allen Kingsbury, 1st Massachusetts Infantry, in a letter to his parents, February 6, 1862

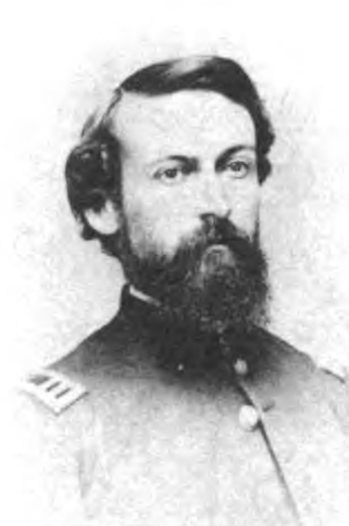

John D. Billings in 1865

“Reading was a pastime quite generally indulged in, and there was no novel so dull, trashy, or sensational as not to find some one so bored with nothing to do that he would wade through it. I, certainly, never read so many such before or since. The mind was hungry for something, and took husks when it could get nothing better.”

—John D. Billings, 10th Massachusetts Light Artillery, on the reading habits of his fellow soldiers, in his memoirs

“We read each other’s Papers in 15 minutes after the News Boys bring them from the Office.”

—Mississippi soldier Jerome Yates, on his clandestine interactions with Union soldiers between the lines outside Petersburg, Virginia, in a letter to his sister, July 19, 1864

“I read much more than I should at home.”

—Michigan soldier Phineas A. Hager, in a letter to his wife, March 12, 1864

“The books she sent, whether all her own or borrowed in part, were almost all so badly worn and soiled by the constant use in hands none too clean, as to be of little value afterwards. In fact, that young lady sacrificed her library for our sakes.”

—Wisconsin soldier Melvin Grigsby, on the generosity of Cahaba, Alabama, resident Amanda Gardner, who lent books from her personal library to Grigsby and other Union soldiers held captive at the nearby military prison known as Castle Morgan, in his memoirs

Captain Edward P. Williams

“All are getting anxious to see a newspaper. Everything at home may be all right, or the reverse, but it is all the same to us. We are in blissful ignorance of the doings of the world.”

—Edward P. Williams, 100th Indiana Infantry, in a letter home while on campaign in Mississippi, December 5, 1862

“We spent a good portion of the time reading. We had a library, the assistant Surgeon being Librarian, and the library in his tent. All were allowed the privilege of taking out books, and if any of the boys had books sent them, after reading, they would place them in the library for the benefit of the others.”

—Austin Stearns, 13th Massachusetts Infantry, in his memoirs

“I was fortunate enough to know a boy who had brought a copy of ‘Gray’s Anatomy’ into prison with him. I was not specifically interested in the subject, but it was Hobson’s choice; I could read anatomy or nothing, and so I tackled it with such good will that before my friend became sick and was taken outside, and his book with him, I had obtained a very fair knowledge of the rudiments of physiology.”

—John McElroy, 16th Illinois Cavalry, on his time as a prisoner in Andersonville, in his memoirs

Sources: Civil War Times, 1861–1865 (1902); Annals of the United States Christian Commission (1868); History of the Seventh Regiment Illinois Volunteer Infantry (1868); Annals of the Fifty-Seventh Regiment Indiana Volunteers (1868); The Hero of Medfield (1862); Bell I. Wiley, The Life of Johnny Reb (1943); David Kaser, Books and Libraries in Camp and Battle (1984); Hard Tack and Coffee (1887); Extracts from Letters to A.B.T. from Edward P. Williams (1903); The Smoked Yank (1888); David Kaser, Books and Libraries in Camp and Battle (1984); Andersonville (1879).