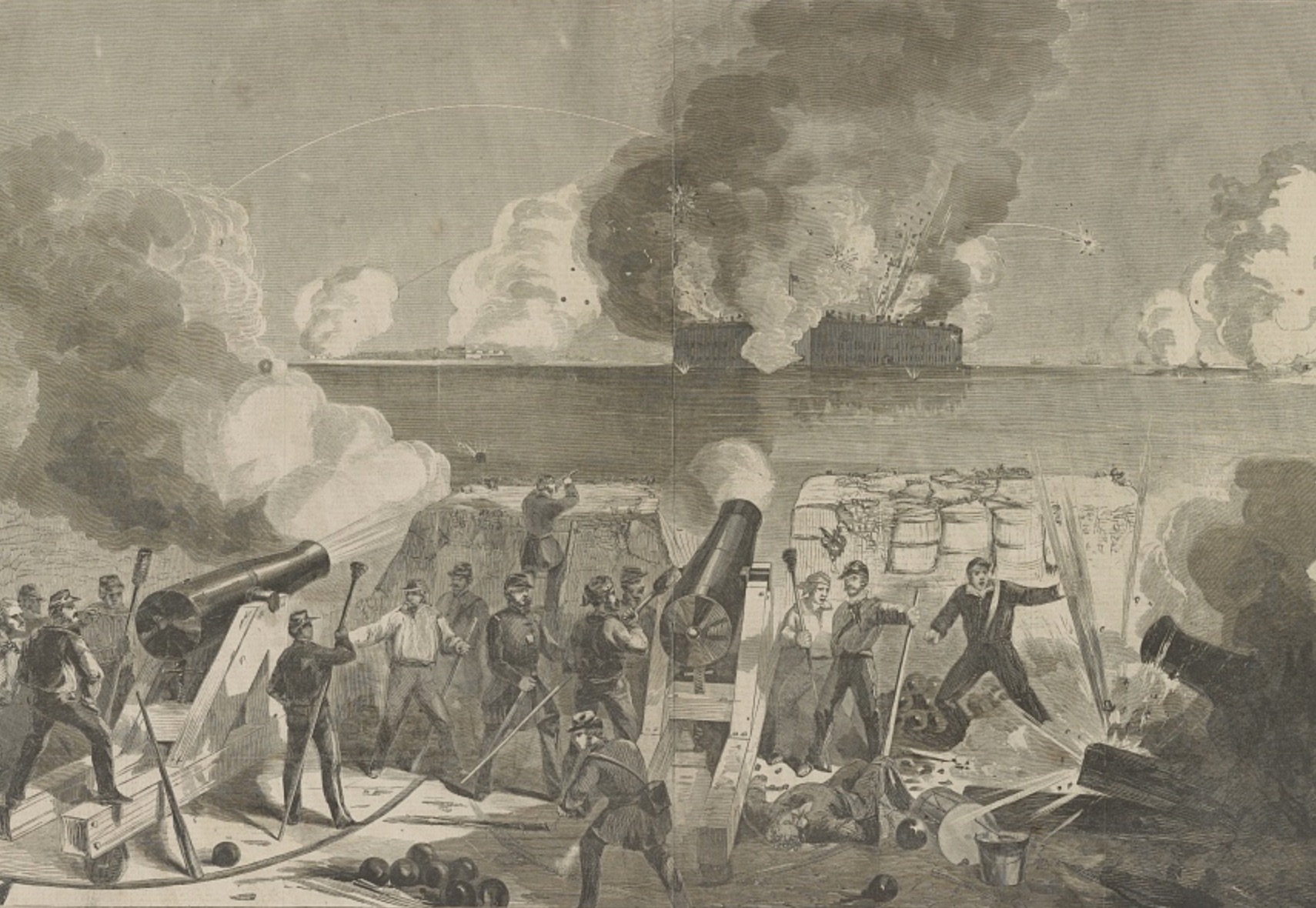

Fort Sumter under fire, April 1861

The literature on the coming of the Civil War is more than vast—it is overwhelming. Choosing just a handful of the thousands of books written on the subject—and the dozens of books absolutely critical to any real understanding of it—is by its nature arbitrary and subjective. That said, the half-dozen titles discussed here offer an outstanding (and readable!) introduction to this fascinating and enormously complicated subject. If all the leading experts in the field were to compile short lists of the books they would most recommend to readers, these titles would be found somewhere on most of those lists, and a few of them would sit near the top of nearly all.

David M. Potter’s The Impending Crisis, 1848–1861(completed and edited by Don E. Fehrenbacher, 1976) is the indisputable starting point for all readers interested in the war’s origins. In lucid, engaging prose and displaying an astonishing depth of insight and wisdom, one of the great historians of the twentieth century offers an absorbing and artfully balanced narrative of the tumultuous period from the end of the Mexican War to the evacuation of Fort Sumter. Potter is at his best when thoughtfully assessing slavery’s role in the growing sectional tensions, never losing sight of the larger political and cultural contexts in which attitudes toward slavery operated.

For the last half a century, almost all historians have agreed that slavery somehow lay at the center of the war’s origins. Naturally, a great many have emphasized Americans’ contentious debate over the institution’s morality, but Michael F. Holt’s landmark The Political Crisis of the 1850s(1978) disagrees, downplaying the northern antislavery crusade as a principal factor in the coming of war. Holt argues that as long as a national two-party system thrived in the United States, Americans felt confident in their government. But in the early 1850s the sudden decline of the Democratic-Whig rivalry—due largely to economic factors—provoked a deep sense of crisis that led Americans to perceive internal threats and enemies. For a variety of reasons, southern fears focused on northern abolitionists, while northern concerns centered on aristocratic southern planters. As a result, the new Republican Party gained popularity in the North and an increasingly unified South came to dominate the Democratic Party. Party politics no longer contained but aggravated sectional conflict, deepening the sense of crisis and leading rapidly to war.

More recently, Marc Egnal has recast Holt’s political explanation as a primarily economic one in Clash of Extremes: The Economic Origins of the Civil War(2009). As long as economic ties united North, South, and West, Egnal contends, shared interests (and the national parties produced by those interests) bound the country together. Once canals and railroads had linked East and West more tightly than North and South, however, economic differences began to outweigh perceived commonalities, unleashing sectional conflict.

Taken together, these works pose a serious challenge to the popular notion that the Civil War stemmed from moral differences over slavery. But neither Holt nor Egnal contends that slavery-related issues were not central to the growing hostility between North and

South, only that attitudes toward slavery were much more intricate and intertwined with other, more immediate aspects of life—political power and economic interest, for example—than most historians generally credit. For the most part, then, their works complicate and complement rather than contradict the many studies that have slavery playing a more direct, central role, including a wealth of wonderful scholarship exploring the profound (and profoundly complex) ties between black slavery and white society and culture in the South. Among this literature, Charles B. Dew’s Apostles of Disunion: Southern Secession Commissioners and the Causes of the Civil War (2001) stands out for its power and persuasiveness. By examining the arguments presented by the Deep South agents who blanketed the Upper South during the Secession Crisis of 1860–1861, Dew unearths white southerners’ most cogent case for secession. What he finds is an astounding focus on a single, dominant line of reasoning: the maintenance of racial dominance. Secession agents warned again and again that submitting to Republican rule would mean emancipation, and with it racial equality, race war, and racial mixing and degradation.Two other recent books bring a more focused, human perspective to the specific attitudes, decisions, and events of the period, exploring with vivid narrative flair and brilliant insight the fascinating point where historical forces met individual ideas

and decisions. William W. Freehling’s Secessionists Triumphant, 1854–1861(2007), the long-awaited conclusion to his two-part epic, The Road to Disunion, presents the best broad account of the southern role in the war’s origins in generations. Edward Ayers’ In the Presence of Mine Enemies: The Civil War in the Heart of America, 1859–1863(2003) takes a microcosmic look at two remarkably similar communities, one in southern Pennsylvania, the other in northwestern Virginia, separated by just 200 miles and the institution of slavery. Together Freehling and Ayers provide their readers with an unparalleled understanding of how Americans both powerful and ordinary perceived the momentous events of their troubled times, and how and why they reacted as they did—as well as an important reminder that the course of history is dictated by human decisions and often could have turned out differently.

Varying levels of discontent and violence have always been a part of American democracy, but only once has the political system utterly failed to contain the country’s broad social, cultural, economic, and constitutional differences. The result was a unique four-year period of massive, organized carnage that devastated a generation and transformed the republic in ways we still grapple with today. Historians have debated the causes of that rupture for a century and a half. No half-dozen books can give readers a full sense of those debates, but the titles listed here offer a fascinating and illuminating overview of key events and crucial questions.

Russell McClintock, author of Lincoln and the Decision for War: The Northern Response to Secession (2008), is currently working on a biography of Stephen A. Douglas.

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2011 (Vol. 1, No. 1) issue of The Civil War Monitor.