Author Tony Horwitz

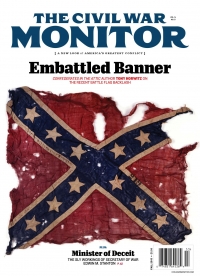

Tony Horwitz: There’s been low-grade warfare over the Confederate flag for decades, so I wasn’t surprised to see this battle flare anew. What did surprise me was that the fight over South Carolina’s flag leapt like wildfire to other states and other symbols. Almost overnight, it seemed, every emblem, name, and monument related to the Confederacy was suddenly up for grabs.

There are many reasons for this turnaround, including the South’s fast-changing demographics, Republican politics, the “Black Lives Matter” movement, and the power of the Internet to spread information and mobilize far-flung Americans. The swiftness and range of the campaign also says to me that this reckoning was long overdue.

It’s not news that the battle flag is deeply offensive to a large portion of the South’s population. But the current debate reveals a broader, pent-up desire to liberate the South from a mythic and burdensome narrative that misrepresents the region as a whole. The Lost Cause, and almost all the monuments to it, arose in the late 19th and early 20th century, when Jim Crow was at its height and the South was still predominantly agrarian, impoverished, and isolated. That stopped being true a long time ago, and increasingly so in the last few decades, as the South has become an economically vibrant and globalized region of roughly 100 million people.

I suspect future historians of this moment won’t simply study why the tide turned against Confederate symbols so dramatically in June 2015. They’ll question why in the world battle flags and other emblems were still being so prominently displayed a century and a half after Appomattox.

Is this a watershed moment in the history of Confederate memory? Or in American culture more generally?

TH: We’re clearly witnessing a watershed moment in the memory of the Confederacy and of our history generally. What started as a movement to furl a piece of cloth has exploded into a national debate over remembrance and memorialization of the Civil War. Until recently, I suspect, most Americans didn’t give much thought to driving down Jeff Davis Highway, serving at military bases named for generals who fought against the U.S., or passing statues to ardent advocates of slavery and secession. This was all just part of our landscape, like McDonald’s Golden Arches. Now, many Americans are at least pausing to reflect on these names and symbols and whether they’re appropriate.

More broadly, there’s been recognition that no symbol is static; the time, context, and audience all matter. The Rebel flag may have been seen as a battle standard to a soldier charging behind it at Gettysburg in 1863. The same flag signaled something very different a century later, when Governor George Wallace hoisted it above the Alabama State House. One person’s heritage is another person’s hate.

The brouhaha over symbols has also brought renewed attention to the true history of the Confederate cause. Let’s be honest. Most students of the Civil War, North and South, have long preferred to dwell on the great leaders and battles and heroism of soldiers and civilians, rather than focus on the knottier and more divisive issues underlying the conflict. We don’t ignore these issues, but most of us were drawn to the war in the first place by its drama and, yes, its romance. We want to share our knowledge and passion peaceably (and for some of us, profitably) with as wide an audience as possible. Shining a laser light on slavery and the racism of white Americans in 1861 raises uncomfortable questions and risks spoiling the reverence many of us feel for that era.

Meanwhile, Americans who don’t share our keen interest in the Civil War and history generally have continued to absorb a vague and sanitized understanding of the conflict. In polls, more Americans cite “states rights” than slavery as the primary cause of the conflict. Millions of visitors flock to former slave plantations, attracted, for the most part, by the lingering Gone With the Wind romance surrounding the Old South’s “way of life.” Many Americans believe that thousands of slaves and free blacks fought willingly for the Confederacy in defense of their “homeland.”

Scholars, of course, have been shredding such fictions for decades, and presenting the clear and overwhelming evidence that slavery was the “cornerstone” of the southern cause, as the Confederate vice president Alexander Stephens famously stated. Thanks to the current debate, and the Internet, which makes the primary documents so easy to disseminate and access, I like to think many Americans are receiving a bracing tutorial on slavery and its role in the Civil War.

How deep do you think this surge against Confederate symbols will go? Should we be debating high school sports teams’ names and Confederate flag merchandise, or can the quest to purge our public spaces from Confederate symbols be taken too far?

TH: This campaign has a long way to go, in part because there are so many names and statues and mascots out there. Also, this issue has migrated from the state to the federal level, and downward to cities, towns, counties, school districts, and other jurisdictions that must debate the fate of hundreds, if not thousands, of names, monuments, and other emblems of the Confederacy—not to mention all the merchandise.

In some cases, changes will likely occur without much of a stir. It’s relatively easy to furl a flag in a government building, move a bust of Nathan Bedford Forrest from the Tennessee State Capitol to a nearby museum, or change the name of a state highway that few care about much in the first place. But what about the towering statues on Monument Avenue in Richmond, or the much smaller ones on courthouse squares across the South, or others that are owned not by the public but by organizations like the United Daughters of the Confederacy?

There’s another complication: Not all Confederates and monuments are alike. Should we treat a political leader like Jefferson Davis the same as a military general? Should Robert E. Lee be swept into the dustbin of history with the notorious Forrest? What about Confederate soldiers, most of whom weren’t slaveholders and many of whom were draftees rather than volunteers? We don’t regard the Vietnam War memorial as an endorsement of U.S. policy in Indochina. Should we revile hundreds of thousands of southerners, and take down monuments erected to them, because they fought and died for a cause that most Americans now regard as unjust?

In debating these questions, I hope Americans don’t succumb to reflexive overreach and scrub history as we’re trying to correct its wrongs. For instance, I’m already hearing instances of educational games and DVDs being pulled from shelves and websites because they in some way incorporate the Rebel battle flag. And Confederate reenactors, most of whom regard themselves as educators or “living historians,” wonder if they will be able to appear in public without being shouted at or spit on.

I also hope most of the monuments will remain standing, because they’re vivid historical documents in their own right. For me, studying a stone Rebel and reading the florid inscriptions give tremendous insight into the psychology of the Lost Cause and those who saw fit to put up these monuments. Rather than tear these monuments down, let’s add interpretive plaques that teach the public about the long, dark era of white supremacy and racial subjugation that gave birth to them.

To read the rest of Tony’s Horwitz’s comments on the recent backlash against the Confederate battle flag, see the Fall 2015 (Vol. 5, No. 3) issue of The Civil War Monitor, which is now available for purchase at The Civil War Monitor Store.