John Banks

John BanksAn aerial view of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad line and Green River Bridge.

Plagued by my god-awful wanderlust, I pack my 8-ounce drone and head north from Nashville to Hart County, Kentucky. I figure it’s high time for a first visit to the Munfordville battlefield, where from September 14-17, 1862, Braxton Bragg captured 4,000 Union army prisoners in what was a prelude to a far bloodier battle at Perryville in October.

What a sublime day it was for battlefield tramping and drone flying: deep-blue sky above splashes of fall colors, the rich golden leaves propelled by only the hint of a gust.

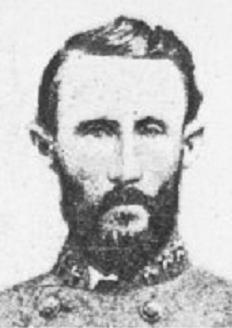

With no humans in sight, I direct my technology over the Louisville & Nashville Railroad line and Green River Bridge and then above the monument for Colonel Robert Smith of the 10th Mississippi Infantry, a 26-year-old Scotsman mortally wounded in an unheralded battle near a meandering Kentucky river.

Surrounded by an iron fence, the 21-foot obelisk paid for by Smith’s brother stands on private property a few yards from the railroad track. Nearby sit gray-granite markers for the 7th, 9th, 10th, 29th, and 44th Mississippi infantry regiments, whose soldiers were among the roughly 700 Confederate casualties in the battle.

Yards from my drone takeoff point stands a replica of the stockade that guarded the rail line at the time of the battle. In the far distance to my left, spanning the Green River, I spy the railroad bridge whose piers are said to be pockmarked with battle damage. The warning sign on the modern bridge in use today, steep slopes toward the river, and a lack of fortitude prevent my inspection.

Over the very ground where I stand, Mississippians under Brigadier General James Chalmers attacked Indianans early on the morning of September 14. “A light fog hung over the river and pointed out the course it took in its windings through the valley,” a private in the 10th Mississippi recalled. “The sky was reddening in the east and shed a soft glow over the intervening fields, the enemy’s camps, the red lines of earthworks, and the rich forests beyond.”

Later, while piloting the drone near the Anthony Woodson farmhouse that predates the war, I spot a gentleman walking on the Old Dixie Road.

“Was the battle fought out in this field?” I ask, pointing to the rolling ground in the near distance.

“See that berm?” he says, gesturing to a hilltop in the far distance and the remains of Fort Craig, a U.S. Army five-pointed earthen star fort on private property. “It was fought roughly in this field to up there.”

John Schlinker, 70, is a longtime local and Kentucky native and a retired U.S. Air Force photo analyst. Out for his morning constitutional, he didn’t expect to encounter a gabby tourist who enjoys showing off his drone-flying skills.

John Banks

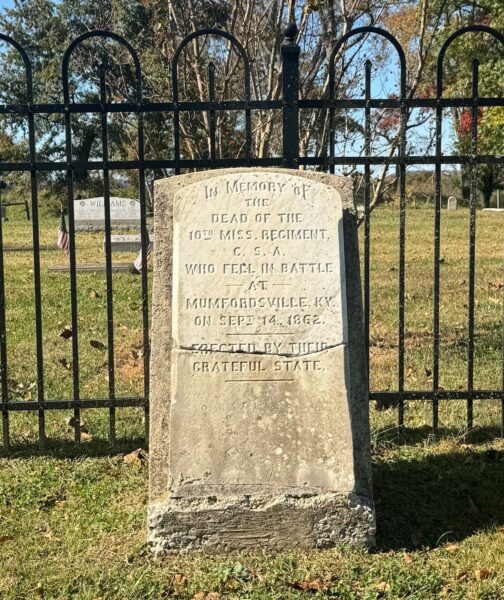

John BanksA marker dedicated to the men of the 10th Mississippi Infantry killed at the Battle of Munfordville, Kentucky

“Wanna walk with me?” says my new friend. “We can see the cemetery and get a closer view of the fort.”

Just outside the cemetery fence stands a broken old marker in memory of the dead of the 10th Mississippi who fell at Munfordville. In the small graveyard, the site of a church torched by the Union army during the battle, Schlinker points out the graves of his kin, including a great-grandfather who served in the 21st Kentucky Infantry (USA).

Right here, on this October day back in 1861, the infamous Confederate raider John Hunt Morgan and dozens of his men joined up.

“Used to play up here as a kid,” Schlinker says wistfully of the fort and surrounding fields.

Tall trees and weeds stretch skyward from the interior of Fort Craig, which was built on the site of an earlier Confederate fort. On the first day of the battle, a ditch and abatis made from beech trees protected the fort, manned by soldiers under the command of Colonel James Wilder. Among them were men and boys of the 67th Indiana Infantry, barely four weeks into their term of service.

“[I]n the calmness of the hour, great gray streaks of the morning dawn began to appear in the east and shoot their silver threads of light across the blue fields of heaven and the dew drops from the leafy boughs began to fall and beat the reveille of early morn,” Reuben B. Scott, a veteran of the 67th, wrote of that first day. “Suddenly, ‘BOOM’ goes a cannon over in our front and a shell goes screeching through the air, leaving a brilliant meteoric streak in its wake.”

On this tranquil afternoon, the scene belies the horror of September 14, 1862, when screaming Rebels besieged the small fort in a “maddening rush to death.” Scott likened the fighting here to a “Hoosier squirrel hunt drill.”

John Banks

John BanksAn aerial shot of the ground where Fort Craig once stood.

Yards from us, 30-year-old Major Augustus H. Abbett of the 67th Indiana climbed the parapet at Fort Craig while the fighting swirled about.

“Shoot low!” he cried moments before Rebel lead killed him.

Scott recalled that after a brief lull, “the Rebel lines fetch a demoniacal yell and with glittering bayonets come on a third time on their march to death, beneath a cloud of smoke.”

The Indianans bravely held off the Confederates, who asked for a temporary truce to bury their dead. More than 100 Rebel bullets had perforated the 34-star U.S. flag that flew at the fort. Two days later, reinforced by Bragg, the Confederates overwhelmed the Union army, forcing its surrender.

“They were all dressed as if for the ballroom and appeared to look down in pity upon us,” the 10th Mississippi private wrote of the Federals. “I cannot tell how angry this made me.”

At the cemetery, Schlinker and I watch my drone soar above Fort Craig, revealing the distinctive five-star-pattern of the site of so much death, and fly off toward the Green River railroad bridge. Then the modern marvel races out of our sight. Ten minutes later it returns, abuzz, and lands at our feet.

What a grand day at a site so terrible long ago.

John Banks is author of A Civil War Road Trip of a Lifetime and two other Civil War books. A longtime journalist (The Dallas Morning News and ESPN), he is secretary-treasurer of The Center for Civil War Photography. He lives in Nashville with his wife, Carol.