Navy Lieutenant W.T. Glassell was furious that his faithful service was being questioned when he landed in Philadelphia in early 1862. He was coming off a long tour that had taken him and the crew of 25-gun screw sloop Hartford to the East Indies Squadron. Even when threatened with imprisonment, he insisted that the oath he already had taken to uphold the Constitution was more than sufficient for now.1

Although he wrote out a letter of resignation dated Dec. 4, 1861, it was never delivered. In these testy days following First Manassas and Ball’s Bluff, a Virginia-born officer’s word was not good enough. He was “dismissed” from the Navy in December. Little could the Union authorities who cashiered him after 15 years of service and sent Glassell to Fort Warren in Boston harbor without trial know that they soon would be fighting one of the Confederacy’s most daring officers in a nasty new kind of war.2

Long after the war, Glassell wrote that those eight months hardened him in such a way that “even President Hayes would now acknowledge that it was my right, if not my duty to act the part of the belligerent” after being exchanged as a prisoner of war in a conflict he hadn’t then joined.3

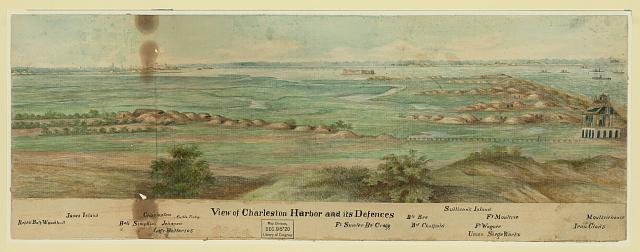

Now, the 30-year-old left the rank of the neutrals and accepted a lieutenant’s commission in the officer-rich and ship-poor Confederate Navy with orders to report to Charleston. From the time when the South Carolina port city hosted the convention that took the state out of the Union in December 1860 through the almost 34-hour bombardment of Fort Sumter in April 1861, punishing and recapturing Charleston assumed an intensity in the Lincoln administration’s war plans that rivaled the “On to Richmond” cry of the North’s newspapers.

Glassell was entering the cockpit of the asymmetric defensive strategy of the chastened Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard, still a hero in the Low Country for Sumter and his victory at First Manassas. President Jefferson Davis had found Beauregard irritating as a commander outside of Washington and irascible as a commander in the West. He used the general’s unasked for leave to recuperate from the battle strain of Shiloh and the evacuation of Corinth as the reason to oust him from command of the Army of the Mississippi in late June 1862.4

The “Little Creole” took his time that September in studying the defenses already in place after being ordered to what seemed a backwater in a shooting war. But the reception he received upon his arrival from citizens and authorities like Governor Francis Pickens soothed his feelings. He would do his best in Charleston until he received orders to again lead troops into battle. Barely waiting for his predecessor John C. Pemberton to take command of forces near Vicksburg, Beauregard wanted more and better obstructions – from ripping up the city’s cobblestone streets to slow down invaders on the water to laying mines carefully to channel old and new classes of “iron sea elephants” into the large guns of expanded batteries and reinforced forts to running rope lines from land point to land point to snarl screw propellers in the harbor.5

Somewhat surprisingly from a career Army officer, an artillerist and engineer, he had an open mind when it came to almost all things naval – be they ideas on mounting spar torpedoes on row boats, building submersibles, and submarines to attack blockaders, and sending the city’s two harbor defending ironclads on a daring night attack on the Union fleet. Following the military dictum, when in charge, be in charge, he didn’t hesitate to wrest control of men and equipment when he believed it necessary to defend not only Charleston, but Savannah and coastal Georgia, and Florida.6

One middling young naval officer, Glassell, played a leading role in many of these episodes. His entry into the world of “destructionists and capturers” began conventionally enough as deck officer in charge of ironclad Chicora’s first division. In a combined attack with ironclad Charleston Jan. 30, 1863, on the Union fleet to raise the blockade at least temporarily. If he had been asked how to attack under the cover or darkness in an ironclad, Glassell’s answer would have been simple. Ram the wooden blockaders at “full speed.” Instead “older and perhaps wise officers” ordered him to fire on Keystone State as it was bearing down on Chicora. His division’s shot killed 21 Union sailors, wounded another 15, and Keystone State’s flag was taken down in surrendering, but in the fighting was raised again and ship sailed away.7

Glassell and Captain Francis Lee, an Army engineer, realized that time was not on the side of the Confederacy in Charleston harbor. As shipyards in and around the Ashley and Cooper rivers struggled to find engines, armament, and iron plating for Southern ironclads like Chicora, the Union could build 10 ironclads “of a superior class almost invulnerable to shot or shell.” Lee by then was experimenting with a spar, a long pine pole, attached by socket to a rowboat, making it maneuverable; and at the end of the pole was a torpedo with “thirty or fifty pounds of explosives” that was under six to seven feet or water. The idea was ram the spar into a ship below its waterline and the iron plating the operator in the boat’s front would be shielded by iron from expected gunfire from the ship’s deck, then set off the torpedo and safely back the boat away.8

“I believed it should be our policy to take immediate steps for the construction of a large number of small boats [with engines] suitable for torpedo service and make simultaneous attacks … before the enemy should know what we were about.”9

At 61 and with more than half a century in the Navy, Commodore Duncan Ingraham, commander of naval forces in Charleston, dismissed Glassell’s “new fangled notions” out of hand. But the lieutenant pressed on – knowing where he could find the money in Charleston to build those deadly rowboats. He went to “my friend,” George A. Trenholm, one of the wealthiest men in North America and the head of the South’s largest trading firm and its financial agent in Europe.10

While Trenholm provided the money for the rowboats, Ingraham held firm against wild notions of any kind. This time, citing Glassell’s age and rank, the commodore said he was not qualified to lead an expedition of this size. He could command a boat in Ingraham’s view, but still the ranking officer did not authorize an attack on the lieutenant’s target of choice, Powhatan, an 11-gun paddle steamer. Glassell’s persistence eventually paid off on March 10, 1863.

At 1 a.m. with “the young moon gone down,” he and six other men set off on the “ebb-tide in search of a victim.” He ordered his men to keep rowing even if they were discovered “until our torpedo came in contact with the ship.” Several hundred yards away from the target, voices from the deck demanded to know “What boat is this?” Glassell shouted back nonsense “and stupid answers” as he ignored repeated orders to stop or they would be fired upon . “I trusted they would be too merciful to fire on such a stupid set of idiots as they must have taken us to be.”11

As they closed within forty yards, aiming for the a spot just below the gangway on Powhatan’s port side, James Murphy suddenly backed his oar stopping the rowboat. At that instant, Glassell didn’t know why Murphy did what he did, but soon enough the other men stopped rowing and the rowboat “drifted with the tide past the ship’s stern.” The Union deck officer and sailors now armed with rifles were taking no chances and kept shouting to Glassell to stay where he was and were ready to launch a boat of their own.

Murphy, who a few weeks later deserted, threw his pistol overboard and scrambled to grab the pistol of the man next to him but failed. Glassell believing he “never was rash, or disposed to risk my life or that of others” drew his weapon and ordered the men to cut loose the torpedo so they could escape. The men quickly followed his command and began rowing quietly but “with all their strength” away from their intended target.12

Back in Charleston shortly after daylight, Glassell was convinced that spies ashore had tipped the Union Navy off to the torpedoes but counted himself lucky that he had only lost one torpedo and no men. Steam power was the way to attack. He didn’t want to take a chance on having another Murphy, who at first appeared ashamed, foil well-laid plans. For now, Glassell’s work in the Low Country was done as he was ordered to Wilmington to complete the ironclad North Carolina.13

While Ingraham moved into more administrative duties, Glassell’s commander aboard Chicora, Captain John Randolph Tucker, took over active operations. About a decade younger than the commodore but with 37 years of naval service, Tucker believed in the spar torpedo, especially against the gathering number of Union monitors.14

Thirty miles up the Cooper River from the city on Dr. St. Julien Ravenel’s hidden away plantation, Theodore Stoney, another of the principals in the Southern Torpedo Company, was rushing to complete the privately-built and paid for but with Beauregard’s blessing cigar boat. Named David, the submersible with its discarded locomotive coal-burning engine, unseasoned wood covered hull with metal plating wasn’t a work of art, but its stealth on dark nights and armed with a spar torpedo made it a formidable opponent of even the Union’s most powerful ship New Ironsides, which repeatedly pounded Confederate fortifications during the siege.15

Stoney’s and Ravenel’s work may have been isolated, but there were others like James McClintock and Horace L. Hunley in Charleston busying themselves in constructing special “torpedo-boats” whose work “were curious things to a landsman’s eye” in and around the city. As patriotic as they were, the private inventors also had a $100,000 incentive provided by Trenholm’s company to sink New Ironsides or Wabash and $50,000 to sink any of the monitors.16

With a new land and sea attack likely on the sea island batteries and forts and Charleston itself, Glassell was ordered back South, not for his services but to return the eight men he had with him to service on the gunboats in the harbor. “There was nothing in particular for me to do.”17

How Glassell knew Stoney he doesn’t make clear, but it was probably through Francis Lee. Nonetheless, he called him “my esteemed friend.” At a meeting in Charleston, Stoney said that the David had been shipped to the city by rail and was being finished in the port. James Stuart, who used Sullivan as his last name to conceal his identity, agreed to be the fireman. J.W. Cannon came aboard as pilot.18

Glassell volunteered to help with the trial work. Already, J.H. Tomb volunteered his engineer services. Lee was available to work on the copper torpedo that was to be loaded with 100 pounds of rifle powder and “provided with four sensitive tubes of lead, containing explosive mixture.” The spar projected about 14 feet from the front of the now bluish painted submersible.

Being the prepared commander, he took on four double-barreled shotguns and as many revolvers as extra armament and four cork life preservers as they began their trials. David reached speeds of six or seven knots. He also knew from the interrogation of deserters and prisoners that the fleet was expecting some kind of torpedo attack, likely based on his attempt on Powhatan and earlier try at New Ironsides. That meant the shotguns would likely have to take out the officer of the deck to succeed. There also would be riflemen rushing to the vessel’s side and possibly canister or grape shot as the attack rolled on. With all that in place, Tucker signaled his approval of an attack at Glassell’s discretion, so did Beauregard. But a rocket from Richmond landed ordering the lieutenant back to Wilmington. “This was too much!,” and he now let Tucker “make my excuses to the Navy Department.”19

Shortly after a starlight night fell on Oct. 5, 1863 and on the ebb-tide with a light breeze from the north, Glassell and his men headed out from the Charleston wharf. The water was smooth as he headed for New Ironsides attack. They slipped unseen past the picket boats near Fort Sumter, and Glassell could see the Union armada at anchor between the David and the camp-fires of 20,000 Union soldiers on Morris Island. This was what he had imagined in the aborted rowboat attack. The damage that could have been done then couldn’t compare to the havoc ten to a dozen Davids armed with spar torpedoes could have done this night. It was what he was thinking as he waited for the 9 p.m. signal gun firing to launch the attack on “the most powerful vessel in the world,” an exaggeration.20

David was off the ship’s starboard side. Glassell took charge of the helm from the pilot. He was sitting on the deck and working the wheel with his feet aiming for a spot near the gangway and a shotgun at the ready. He handed the pilot a double-barreled shotgun. He ordered the engineer and fireman to stay below and give the David as much steam as possible.

About 300 yards away, a sentinel spotted the submersible and began hailing it. “I made no answer.” The officer of the deck demanded, “What boat is that?” as the submersible closed to within 40 yards. Glassell fired the shotgun severely wounding the officer named Howard in the groin and the acting ensign died three days later. He then ordered the engine stopped. “The next moment the torpedo struck the vessel and exploded” then the David plunged violently. But instead of going off at six to seven feet under water, the torpedo exploded about three feet below the waterline where the iron was 4 ½ inches thick backed by 27 inches of wood. The explosion, however, caused a huge column of water to wash over the deck and down the hatchway dousing the fires. Glassell told his men that their only chance for escape was to don the life preservers and swim for it.21

Rifle and pistol fire rained down from the New Ironsides. A nearby monitor now joined the fight. For more than a hour, Glassell struggled with the cold and the wind when a boat from a transport hauled him out of the water and “to their surprise” found “they had captured a rebel.” They took him to Admiral John Dahlgren, the ordnance genius now commanding the Union Navy at Charleston who sent him to Ottawa. Glassell was immediately recognized there by its commander, William Whiting. Whiting explained that his orders were to put Glassell in chains and double irons if he was obstreperous. Glassell said that he would adjust to the circumstances of his capture. Whiting appealed to Dahlgren to give the Confederate a parole on the promise not to escape. Sullivan got to the chains of New Ironsides where he was rescued and then imprisoned.22

Unknown to Glassell, Cannon, who could not swim, clung to the David as it drifted slowly away from the large warship. “Seeing something in the water, he hailed and heard, to his surprise, a reply from Engineer Tomb.” Tomb reported that he found “no quarter would be shown, as we called out that we surrendered.” They re-started the fires and Cannon, winning for “himself a reputation” as a heroic pilot, headed for the city. Even though they were fired upon several times, they made it safely to Atlantic Wharf about midnight.23

Glassell was on his way back to Forts Lafayette and Warren where he was held for more than year. During this confinement, he was promoted for “gallant and meritorious service” as the Confederacy was sinking inexorably into defeat. New Ironsides was pulled off station and spent months in dry-dock repairs. “The Ironsides never fired another shot (on the coast of South Carolina) after this attack upon here,” but it returned in time to attack Fort Fisher and close the port of Wilmington.24

Like Admiral Samuel F. DuPont before him, Dahlgren never succeeded in blasting Charleston in submission.

Long after the war, Glassell–who remained a bachelor and moved in 1866 to a quiet life raising citrus in California–wrote, “The time has arrived when I think it my duty to grant pardon to the government for all the injustice and injury I have received.”25

John Grady, a former managing editor of Navy Times and retired communications director of the Association of the United States Army, is completing a biography on Matthew Fontaine Maury. He has contributed to the New York Times “Disunion” series, the Civil War Monitor, and is a blogger for the Navy’s Sesquicentennial of the Civil War site.

1 W. T. Glassell, “Reminiscences of Torpedo Service in Charleston Harbor” (hereafter Glassell, “Torpedo”), Southern Historical Papers, Vol. 4, November 1877, Richmond, 225-235; W.T. Glassell, W.T. Glassell and the little torpedo boat “David” (herafter Glassell, David), Privately Printed, Los Angeles, 1937 in Museum of the Confederacy collections in Richmond, 1.

2 John Witherspoon Dubose, “Lieut. William T. Glassell, of Alabama,” Confederate Veteran, Vol. 24, No. 4, May 1916 , Nashville, 193-195.

3 Glassell, “Torpedo,” 225-235.

4 G.T. Beauregard, “Torpedo Service in the Harbor and Water Defenses of Charleston,” Southern Historical Society Papers, Vol. 5, April 1878, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2001.05.0040%3Achapter%3D2.10%3Asection%3Dc.2.10.38%3Apage%3D145 (accessed Nov. 15, 2013), Richmond, pp. 147-162; George E. Belknap, “Reminiscent of the Siege of Charleston,” Papers of the Military Historical Society of Massachusetts, Vol. 12, The Society, Boston, pp. 190-198.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Glassell, “Torpedo,” 225-235; Glassell, David, 9; B.J. Sage, Organization of Private Warfare, Bureau of Destructive Means and Measures, Bands of Destructionists and Captors, Privately Printed, probably late 1863, Library of Congress Rare Book Collection.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 W. T. Glassel (c.q.), “Torpedo Service in Charleston Harbor,” Confederate Veteran, Vol. 25, Issue 3, March 1917, 113-116.

11 Ibid; Glassell, David, 10-11.

12 Ibid.

13 Glassell, David, 13.

14 Ibid.

15 David C. Ebaugh, “On the building of ‘The David,”’ South Carolina Historical Magazine, Vol. 54, No. 1, January 1953, Columbia, 32-36.

16 Tom Chaffin, H.L. Hunley: Secret Hope of the Confederacy (New York: Hill and Wang, 2008), 127.

17 Glassell, David, 13.

18 Glassell, David, 15.

19 Glassel, “Torpedo,” 225-235.

20 Glassell, David, 17.

21 Glassell, David, 18.

22 Glassell, David, 19-21.

23 James H. Tomb, “Submarines and Torpedo Boats,” Confederate Veteran, Nashville, Vol. 22, Issue 4, April 1914, p. 168; J. Thomas Scharf, History of the Confederate States Navy (New York: Random House Value Publishing, 1996 reprint), 758-760.

24 Lyon Gardiner Tyler, editor, “Glassell, William Thornton” entry Encyclopedia of Virginia Biography, Vol. 3, http://archive.org/stream/encyclopediaofvi04tyle/encyclopediaofvi04tyle_djvu.txt (accessed Nov. 15, 2013), 350-351; P.G.T. Beauregard, “Torpedo Service in the Harbor and Water Defenses of Charleston” Southern Historical Society Papers, Vol. 5, April 1878, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2001.05.0040%3Achapter%3D2.10%3Asection%3Dc.2.10.38%3Apage%3D145 (accessed Nov. 15, 2013), Richmond, pp. 147-162.

25 Glassell, David, p. 24.