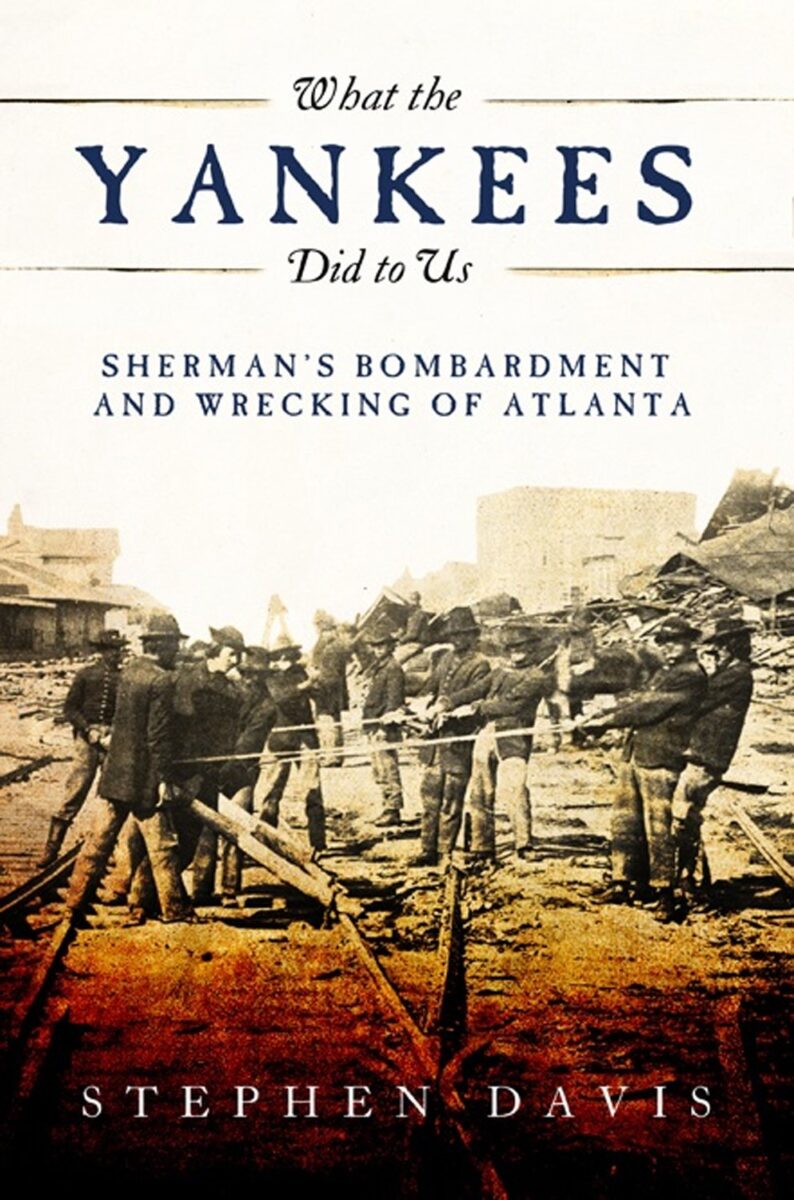

General William Tecumseh Sherman was a very bad man. This is the main point of Stephen Davis’ exhaustive history of the Union capture of Atlanta in 1864.

Davis makes his sympathies clear with his title, which identifies the author with the “us” of Civil War Atlantans and heaps blame on Sherman and the “Yankees” for “wrecking” the city. Acknowledging the many other works on the subject, Davis sets out to provide the most thorough version yet written of Atlanta’s destruction. The result is a massive lawyer-like brief against Sherman and, by implication, the Union war effort. Readers lacking Davis’ partisan zest and love of local detail will find the book a slog. Yet even those put off by Davis’ relentless indictment of the Federals will appreciate the book’s valuable guide to primary sources and its encyclopedic inventory of the damage done to Atlanta in 1864.

After recounting the background to Sherman’s attack, Davis devotes three enormous chapters (each at least seventy-five pages) to the Federal bombardment, occupation, and burning of the city from late July through mid-November 1864. He concludes with a short postscript on how Atlantans have remembered their city’s destruction. Complimented by a lengthy set of images and maps, many of them drafted by the author, What the Yankees Did to Us conveys the feel of everyday life in wartime Atlanta and explains how the city’s nearby geography and its rail connections made it a primary strategic objective for Sherman.

The book’s main focus, however, is Sherman’s wreckage of the city in violation of the accepted the rules of war. Whereas most accounts of Atlanta’s destruction concentrate on the fires set by evacuating Confederates in September and again by departing Federals in November, Davis gives equal attention to the thirty-seven day cannonade of the city in July and August and the destruction of property by Federal occupiers in September and October. In each case, Davis argues that ends failed to justify the means. Sherman’s bombardment killed civilians and brought down buildings but did little to weaken Confederate resistance; tearing apart civilian homes to build temporary shelter for the army needlessly wasted existing structures; the forced evacuation of civilians visited hardship on a few thousand non-combatants who posed no credible threat to an army nearly twenty times their number; and fires lit to deny resources to the enemy when Sherman’s army moved out were unnecessary given the absence of local Confederate resistance by early November.

Davis provides a point-by-point rebuttal to each of Sherman’s “exculpatory calisthenics” given in defense of his actions (322). In place of Sherman’s claim of military necessity, Davis attributes his behavior to personal psychology and, perhaps, insanity. Sherman was driven by “anger and resentment as much at the Southern people and the Confederate government as at Hood and his army” (302). This anger set Sherman apart from his fellow Union commanders. According to Davis, “no other Federal commander involved in a sustained shelling of a Southern city during the Civil War expressed himself so vengefully against a bunch of buildings. At the same time Sherman seemed heedless of the noncombatants” (242). His troops were little better. Davis argues that “many in Sherman’s army enjoyed the burning of Atlanta,” and they engaged the task with “abandon and recklessness” (395-396). He notes that Confederate forces also looted and burned, but any harm done to civilians violated general orders and was caused either by accident or by a few undisciplined enlisted men. Not so for the Union. Its assault on Atlanta’s people and their property was intentional and the plan originated with Sherman.

In addition to his explicit judgments, Davis shades his selection of examples to reflect poorly on Federals and favorably on Confederates. In recounting the escalation of urban bombardment as the war progressed, Davis’ only exception to the rule of disregard for civilian life and property is Confederate J.E.B. Stuart’s “by the book” shelling of Carlisle, Pennsylvania, during the Gettysburg campaign (101-102). Similarly, in the aftermath of fighting on July 22, Davis quotes Union troops boasting of their ability to “cook and eat, talk and laugh with the enemy’s dead lying all around us,” whereas a Confederate officer discusses burying the Union dead (129).

What the Yankees Did to Us fits into a long tradition of partisan histories of the Civil War. As Davis notes, vilifications of Sherman’s destruction of Atlanta date to the immediate aftermath of the war and have carried through the ensuing century and half of historical writing on the subject. As such, this book will find a receptive audience among those invested in remembering the Civil War as a series of Northern atrocities against the South. It may also spark rebuttals from Sherman’s admirers. Otherwise it will disappoint readers interested in questions about the Civil War that go beyond the narrow partisan search for who was worse, the Yankees or the Rebels?

Frank Towers is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Calgary.