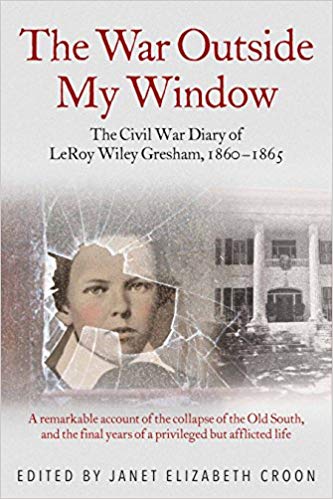

The War Outside My Window: The Civil War Diary of LeRoy Wiley Gresham, 1860-1865 edited by Janet Elizabeth Croon. Savas Beatie, 2018. Cloth, ISBN: 978-1611213881. $34.95.

Georgia resident LeRoy Wiley Gresham (1847-1865) began keeping a diary in June 1860 when he and his father were en route to Philadelphia to consult a physician about the twelve-year-old boy’s failure to recover from an accident that had crushed his leg four years previously, leaving him unable to walk without crutches. He returned home to Macon with a prescription for pain and a recommendation to rest. Although LeRoy (known as “Loy”) did not know it, he was suffering from both pulmonary and spinal tuberculosis, and neither medication nor rest would improve his condition. Nor was LeRoy able to return to Philadelphia for follow-up treatment, for only months after his return home from his trip North, secession and civil war divided the nation.

Georgia resident LeRoy Wiley Gresham (1847-1865) began keeping a diary in June 1860 when he and his father were en route to Philadelphia to consult a physician about the twelve-year-old boy’s failure to recover from an accident that had crushed his leg four years previously, leaving him unable to walk without crutches. He returned home to Macon with a prescription for pain and a recommendation to rest. Although LeRoy (known as “Loy”) did not know it, he was suffering from both pulmonary and spinal tuberculosis, and neither medication nor rest would improve his condition. Nor was LeRoy able to return to Philadelphia for follow-up treatment, for only months after his return home from his trip North, secession and civil war divided the nation.

Over the next five years, LeRoy’s diary charts both his own painful physical disintegration and death and the Confederacy’s equally tortuous path to destruction and defeat. Until the end, LeRoy remained entirely unaware of his own dismal fate; he was equally unconvinced of the Confederacy’s ultimate failure. As late as February 1865, LeRoy, a staunch Confederate supporter, remained optimistic about the outcome of the war. “Things look dark,” he confessed, “but the tide of war may turn at any moment and the skies will be bright, our hearts will be cheered and our Independence achieved” (377). By then almost completely bedridden, LeRoy was less optimistic about his own prospects. “My daily occupation, doing nothing, is becoming more irksome to me every day,” he reflected in March 1865. “I do long for health + active employment” (383). By May 1865, LeRoy conceded both personal and political defeat. “We are under the rod as conquered rebels forever,” he pronounced. As for himself, he was “completely helpless with both legs contracted and one of them almost paralyzed from pain” (393). Over the next few weeks, as the Greshams’ enslaved workers claimed their freedom, LeRoy relied entirely upon his loving parents, John and Mary, his older brother, Thomas, and his younger sister, Minnie, for care and companionship until his death on June 18, 1865.

LeRoy eagerly sought out war news and carefully pasted clippings about the progress of the war in numerous scrapbooks. However, for most of the period covered by the diary, the Gresham family remained fairly insulated from the war’s impact. LeRoy’s father, John Jones Gresham, owned two prosperous plantations totaling more than 1700 acres and supplied by the labor of nearly 100 enslaved African Americans; he also was president of the Macon Manufacturing Company, which produced cotton textiles. While the Gresham family’s financial security came primarily from cotton, the two plantations also supplied the family’s comfortable Macon home with plentiful foodstuffs, including fresh and cured meats and a wide variety of fruits and berries, of which LeRoy was inordinately fond. Thus, while LeRoy commented frequently on rising prices for basic necessities such as food, cloth, and fuel, his own family suffered no shortages and seemed to have no difficulty paying exorbitant prices not only for food, medicine, and clothing, but also for luxuries ranging from newspaper subscriptions, novels, diaries, and scrapbooks to wine, whiskey, cakes, and candy. In addition to living in comfort, the Greshams were able to avoid either military service or Union occupation until the final year of the war; even then, John Gresham was able to arrange to keep his son Thomas on special duty as a surveyor, away from the front lines, while he himself apparently was only on reserve duty with the local militia.

While full of commentary on the war—including news reports on victories and defeats, hopes of recognition by France and England, descriptions of successive Confederate flag designs, reflections on proposals to arm African Americans in both the Union and the Confederacy, and finally descriptions of Union occupation and African American emancipation—LeRoy’s diary is primarily a record of his struggle with his own symptoms, which included a persistent cough, an aching back, and contracted legs. Other symptoms, such as nausea and headaches, may well have been exacerbated by the constant stream of medications LeRoy turned to in search of relief from pain and sleeplessness—mostly patent medicines containing opiates, such as Dover’s Powders, but also poisonous substances such as belladonna and mercury. By the end of the diary, LeRoy was taking morphine or laudanum (both opium derivatives) nearly every day.

Despite his constant pain and growing drug dependency, LeRoy was a bright and observant youngster who filled his diary with comments on his own, his family members’, and—to a lesser extent—the Gresham slaves’ daily activities. A voracious reader, LeRoy kept a detailed record of his reading material, which included an endless stream of novels by both male and female authors, popular and religious periodicals, and both Union and Confederate newspapers. LeRoy also occupied himself by keeping a series of scrapbooks of clippings about war news, working mathematical problems and chess solutions, assisting his mother and sister with their work for the soldiers’ aid society, and playing chess, checkers, backgammon, and marbles with his brother and father. When he was well enough, he explored the outdoors in a specially constructed wagon pulled by either a slave attendant or a family member and practiced shooting—either with a bow and arrow of his own construction, or with a pistol loaded with shot that he molded himself.

The original seven-volume diary, held at the Library of Congress, came to the publisher’s attention when it was featured in an exhibit on the Civil War in 2012. Editor Janet Elizabeth Croon annotated the diary, providing a dramatis personae of the many friends, family members, and household slaves mentioned in the diary as well as footnotes commenting on the accuracy (or lack thereof) of LeRoy’s reports of military and political developments. A “medical afterword” by physician Dennis A. Rasbach offers not only a diagnosis of LeRoy’s previously unidentified illness, but also a discussion of some of the medications he took. The publication of this edited and annotated source has made an absorbing account of the Civil War South from the perspective of a privileged but afflicted youth available and accessible to a broad audience.

Anya Jabour is Regents Professor of History at the University of Montana and the author of Topsy-Turvy: How the Civil War Turned the World Upside-Down for Southern Children (2010).