John Yates Beall’s friends stirred up a hornet’s nest of protest over the death sentence he had been given by a military commission sitting on Governor’s Island in New York harbor. Nowhere was the swarm busier than Washington, buzzing the White House to at least delay the execution or commute the sentence. Beall, an “acting master” in the Confederate Navy and carrying out orders from Confederate officials in Canada, was then and still is at the center of one of the “leading and remarkable cases in ‘The American State Trials’ of the Civil War.” Only the Lincoln conspirators’ military commission hearings topped it and its ramifications have bearing today in the cases of those men being held at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba as terrorists.

On every charge and all but one specification (because a date was incorrectly entered), the six-member commission found Beall guilty on February 7, 1865, of seizing two steamers on Lake Erie in September in an aborted attempt to liberate Confederate prisoners being held on Johnson’s Island off the Ohio Coast and trying to derail a passenger train outside of Buffalo three months later to free several Confederate generals being moved from the Ohio prison camp.

Joseph Holt, former secretary of war and now the Union Army’s judge advocate, and Major General John Dix. The Union commander in the East, were united in their opinion that the Virginian was “a spy, guerrillero, outlaw, and would-be murderer of innocent persons traveling in supposed security.” To his dying day, Beall denied that he approved of the idea of derailing the train.

The two generals pressured President Abraham Lincoln to let the commission’s sentence be carried out.

The facts were undeniable in their minds. Beall had been arrested in the Niagara Falls train station with another Confederate agent after the failed train derailment. He had lied about his name, what he had been up to, and was only being truthful about wanting to escape to Canada and having once been a prisoner at Point Lookout, Maryland.

The Union had him in chains before for his piratical seizures on the Chesapeake Bay in 1863. Only the threat of retaliation against Union prisoners being held in Charleston and by Lieutenant General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson in Virginia changed his and his men’s status to prisoner of war.

Times had dramatically changed. The Confederacy was collapsing on every front. Lincoln had been re-elected. Beall was out of luck; his fate was sealed.

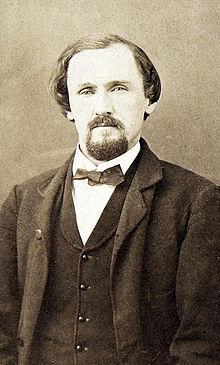

Although it was late at night but knowing the verdict, James McClure and Albert Ritchie, two of Beall’s friends and classmates at the University of Virginia, knocked on the door of the Baltimore home of Francis Wheatley, a friend and “a gentleman of influential associations in Washington.” The two young lawyers needed a “fixer” to open doors for them in the capital. On Friday morning, February 17, Ritchie and Wheatley were in Washington. There, they discussed with “several gentlemen from New York” what the next steps had to be. Those steps led them to Orville H. Browning, one of the most prominent “fixers” in the capital and Lincoln’s former law partner. In his office, he told Ritchie and the others that he would draft a petition on Beall’s behalf.

Ritchie, Wheatley, and the New Yorkers next made the rounds of Capitol Hill. They met with surprising success in a Congress dominated by Republicans and Unconditional Unionists. Six United States senators agreed with the petition to delay the execution or commute the sentence. The petition they handed the Speaker of the House was “signed by most of the Democratic members of the House of Representatives and by many Republicans” — ninety-one in all coming for twenty states. Before taking it to the White House Speaker Schuyler Colfax from Indiana also signed.

Browning, Ritchie, and two men from New York went to the White House with the petition. Following an hour-long meeting with Lincoln, “the fixer” came away satisfied that there would be at least a delay. What they did not know then was that the weeklong stay had been given to fix the erroneous date in the only specification on which Beall had not been convicted.

No one in Baltimore, New York, or in Washington among Beall’s supporters knew if there was a new date set for the execution of the young man from a prosperous family in what had been Jefferson County, Virginia. They asked Browning to press the White House for an answer. On that Saturday afternoon back in his office, Browning admitted frankly “he had little hope than we would be able to accomplish more than the respite” with a big “unless.” If Dix agreed, Browning said “he felt assured the President would promptly commute the sentence.”

During the reprieve, Beall’s mother finally was allowed to visit briefly with her son in his cell at Fort Lafayette on the island. “I saw the moment she entered the cell that she could bear it, and that it made no difference to her whether I died upon the scaffold or upon the field.”

With guards still present, she asked, “A pardon, my son — is there no hope?”

“No mother, they are thirsting for my blood. There will be no pardon.”

The new date for the execution was set for Friday, February 24. Beall’s friends were stunned.

That was the next day.

During the weeklong delay, the White House continued receiving a steady stream of Beall advocates: the librarian of Congress; the president of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad; Representative Thaddeus Stevens, the Pennsylvania abolitionist; and Massachusetts Governor John Andrew, one of the staunchest supporters of the Union war effort.

During the evening of Thursday, February 23, Browning again called on the White House. “The president looked badly and felt badly — apparently more depressed than I have ever seen him since he became president.”

The two again went over the case with Browning stressing that there was little purpose in executing Beall. Lincoln’s only concession was an agreement to meet with James Brady, a titan of the New York bar who defended Beall pro bono before the military commission, the next day.

An hour or so later Montgomery Blair, the president’s former postmaster general, and Mrs. John Gittings, wife of a Baltimore railroad man, also tried to have the sentence commuted. They too met with no success.

The matter did not end there that night.

John Forney, secretary of the Senate and founder of the Washington Chronicle, and Washington McLean, owner of the Cincinnati Enquirer, came to the White House with another man, pale and thin who until a few days before had been held at Fort Lafayette as a prisoner of war. The man was Roger Pryor.

Forney, who had been clerk of the House of Representatives before switching parties; McLean, still a caustic critic of the administration, abolition especially, and a power in southern Ohio Democratic politics, and Pryor had been friends before the war.

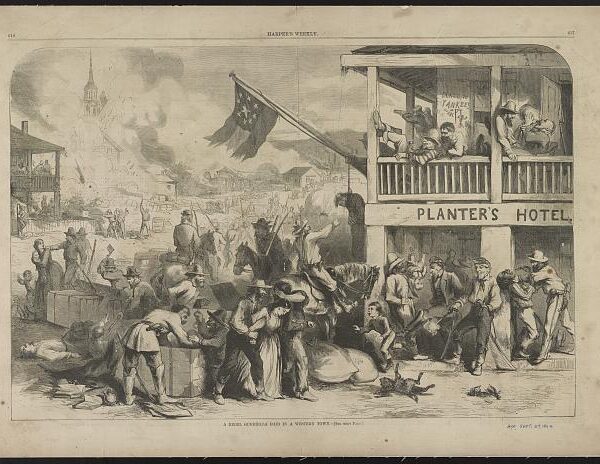

McLean had telegraphed the president that he wanted to arrange a meeting with Pryor, a fire-eating secessionist, former congressman, and Confederate general, in the White House. Having recently returned from a “peace conference” in Hampton Roads, the president said yes.

The meeting began cordially enough.

The knotty matter was Beall’s fate. While held at Fort Lafayette, Beall asked Pryor to represent him at the hearing. Charles Dana, Assistant Secretary of War, scoffed at the very idea of having a prisoner of war represent a spy. Pryor brought copies of Beall’s diaries and wanted Lincoln to read them to understand what a man of character Beall was. The president said he understood Beall to be a man of “social standing and high reputation.” The “nevertheless” to their pleas was a telegram from Dix that the execution was “necessary for the security of the community.” That could have included continuing suspicions that Beall was involved in the mysterious fires set in Manhattan by Confederate agents over Thanksgiving.

Lincoln then shifted to his purpose in agreeing to meet — what to do in the aftermath of the collapse of the “peace conference” talks. He wanted them to understand the reason was Davis’ insistence against all odds that “the sine qua non of any negotiations” for peace was the recognition of the Confederacy as an independent nation. That stance, Lincoln insisted, made Davis “responsible for every drop of blood that should be shed in the further prosecution of the war.” He wanted that message carried to Richmond.

That next morning, Browning waited for Brady at his home, but the New York attorney never called. Instead Wheatley; Andrew Sterret Ridgely, another politically-connected attorney from Baltimore, and a man named Hunter discussed other avenues to use. They had no time to lose. The scheduled execution time was but hours away.

Hearing then that the New York attorney was at the Willard Hotel, Chambers, Wheatley, and a man named Duncan raced there in the hopes that Brady could change the president’s mind.

As Browning and Brady talked, Francis Blair, the founder of the Congressional Globe known as “Father Blair” to distinguish him from his sons, and “The Old Quaker” William H. Stabler were courteously received at the White House but like everyone else given no promises of presidential action.

Lincoln’s position now was that “it was useless for them to have an interview” even with Brady because Beall’s case “was closed.”

So it was.

Ritchie and McClure were with Beall on that cold clear February Friday. He gave them instructions on what to do about his estate — even the photograph he had taken that morning, the handling of his remains, and to inform his mother that he had been engaged to be married, a fact he kept from her. He thanked several Union officers for the kindness they had shown him while confined first at Fort Lafayette and now at Fort Columbus. He also made sure they understood which of his two wills was the one he preferred. Through it all, he had the comforting words of Chaplain Samuel Weston, an Episcopal minister, as they awaited the marshal and the execution party to arrive. It was shortly before one.

Dix had handed out passes to about five-hundred spectators, and there were soldiers seemingly everywhere near the scaffold.

The time was up. When McClure asked for God’s blessing on Beall, the prisoner said, “Ah, no doubt of that” and taking both friends in, added, “God bless you.” As Beall was led away, Ritchie heard him say, “I die in the hope of resurrection, and in the service and defense of my country.”

With the United States marshal and some other officials to the right and Weston on the left reading from the Book of Common Prayer, the noose around Beall’s neck was attached to the rope suspended above. Beall, who had turned away from the adjutant to face south, appeared to be paying close attention to Weston’s reading.

When the chaplain finished, the deputy adjusted the rope and asked Beall if he had anything to say. “Yes, I protest against the execution of this sentence. It is absolute murder, brutal murder. I die in the defense and service of my country.”

With those words, later inscribed on his tombstone in Charles Town, West Virginia, Beall became revered as a martyr to the “Lost Cause,” the John Brown of the Confederacy.

The signal was given the executioner, a convicted deserter, to drop the weight. It was a quarter after one in the afternoon. Beall’s body was left hanging for twenty minutes. Then it was cut down and taken back inside the fort. The New York Times, in its account, wrote, “The fate of this man and each of his fellows as may be similarly convicted will do more to relieve us from the incursions and annoyance of rebel thieves upon our frontiers and stowaway pirates on our merchant steamers, than the employment of an army of guards and detectives.”

John Grady, a former managing editor of Navy Times and retired communications director of the Association of the United States Army, is the author of Matthew Fontaine Maury, Father of Oceanography: A Biography, 1806-1873. He has contributed to the New York Times “Disunion” series, The Civil War Monitor, and is a blogger for the Navy’s Sesquicentennial of the Civil War site.

Selected Sources: Abraham Lincoln papers, Manuscript Collection, Library of Congress, Washington; John Y. Beall, Box 4, Algernon Sullivan Collection, Hundley Regional Library, Winchester, Virginia; John Yates Beall notes, Nat Brandt Papers, University of Rochester, Rochester, New York; John Yates Beall folder, Aylett Family Papers, Virginia Historical Society Papers, Richmond, Virginia; John Yates Beall papers, Special Collections, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, Virginia; “Escape of Prisoners From Johnson’s Island,” Southern Historical Society Papers, Vol. 18, Richmond, Southern Historical Society, 1890: 428-431; “A Plan to Escape,” Southern Historical Society Papers, Vol. 19, Richmond, Southern Historical Society, 1891: 283-289; John Bell, Rebels on the Great Lakes: Confederate Naval Commando Operations Launched from Canada, 1864-1865 (Toronto: Dundurn, 2011); Amanda Foreman, A World on Fire: Britain’s Crucial Role in the American Civil War (New York: Random House, 2010).