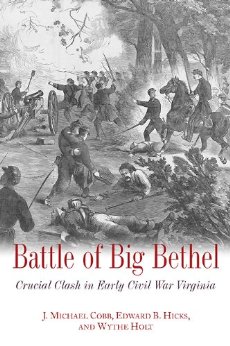

Battle of Big Bethel: Crucial Clash in Early Civil War Virginia by J. Michael Cobb, Edward B. Hicks, and Wythe Holt. Savas Beatie, 2013. Cloth, ISBN: 1611211166. $27.95.

Within weeks of Virginia’s secession, the commonwealth became a battleground. From the western mountains to Manassas Junction, Union and Confederate forces confronted one another. The initial clash—a minor affair—occurred at Philippi in the Allegheny Mountains on June 3. Federal troops routed a small rebel command, resulting in few casualties.

A week later, opposing forces fought the Battle of Big Bethel near the eastern tip of the Peninsula. Unlike Philippi, the June 10 engagement was a real clash of arms in which men were killed, wounded, and captured. In both the North and South, newspapers filled columns with accounts of the fighting. The attention accorded Big Bethel far outweighed its strategic importance. But the war was still a novelty, and the blood of eager volunteers lay upon the ground.

The Battle of Big Bethel resulted from the early concentration of Union and Confederate units on the Peninsula. Each of the warring governments recognized the strategic value of the land between the York and James Rivers. For the federals, the security of Fort Monroe was critical, both to control the waters off the Peninsula and to establish a base for future military operations. For the rebels, defense of the Peninsula blocked the blue-coated enemy from Richmond.

Throughout May and June, Union volunteer regiments arrived at Fort Monroe. The Lincoln administration assigned Brigadier General Benjamin Franklin Butler to command at the fort. Within weeks, camps sprouted outside of the fort as Butler’s numbers exceeded 6,000 officers and men. The general had orders to act aggressively in defense of Fort Monroe.

Meanwhile, at Yorktown, Confederate troops gathered under the command of Colonel John Bankhead Magruder. The rebel commander established a forward defensive position on a ridge above Wythe Creek near Big Bethel Church — less than ten miles from the Union camps outside of Fort Monroe. Under Magruder’s and Colonel Daniel Harvey Hill’s direction, the rebels dug earthworks and redoubts for artillery. By June 10, perhaps 1,400 infantrymen and several cannon manned the works at Big Bethel.

Minor skirmishes occurred between the opponents until Butler ordered an advance on the night of June 9-10. He assigned 4,400 troops to the offensive, but his plans for an attack were too complex for his inexperienced officers and men.

Butler’s second-in-command, Brigadier Ebenezer Pierce, led the Union force. A politically appointed militia officer, Pierce remained in the rear during the fighting. Colonels of individual regiments led the piecemeal attacks, which the Confederate defenders repulsed each time. Magruder’s inspiring resolve and Hill’s skillful leadership steadied their raw troops. The Confederates suffered losses of one killed and seven wounded. Although Union casualties remain imprecise, the Yankees probably lost more than one hundred men killed, wounded, or captured.

Many officers who were to become well-known were on the field at Big Bethel—Magruder, Hill, Robert F. Hoke, Gouverneur Kemble Warren, and Hugh Judson Kilpatrick. And in time, North Carolinians boasted that they were “First at Bethel.” But Big Bethel ultimately became a minor footnote in the history of the Civil War, its casualty list nothing like those generated by the slaughterhouses of Shiloh, Antietam, and Gettysburg.

This study is the fullest account we are likely to have of this engagement. It is well-researched and highly detailed. The book teems with quotes from the participants, including those of local civilians. In fact, one of the book’s best features is a detailed account of the military’s effect on area residents.

Photographs abound, and the authors provide post-battle biographies of both key officers and enlisted men. It must be noted, however, that the authors’ description of the engagement is rather confusing. At times, it is difficult to discern which side an officer or man is on.

The authors conclude that, “Big Bethel demonstrated beyond cavil that the struggle would be intensely pursued and bloody, that Southern arms were steady, capable, and fierce, and that Northern resolve would harden rather than fall away” (265). This might be true, but it is open to argument. Nevertheless, this book is a solid contribution to Civil War history.

Jeffry D. Wert is the author of A Glorious Army: Robert E. Lee’s Triumph, 1862-1863 (2011).