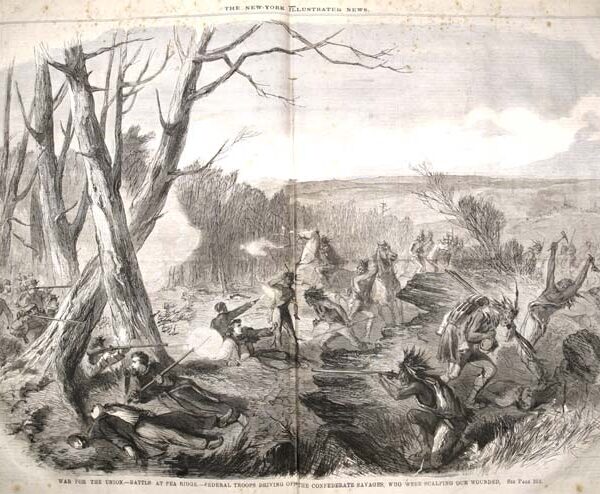

Throughout the Civil War, surgeons performed approximately 60,000 amputations—the most common battlefield operation. Such drastic measures were a consequence of the damage caused by Minié balls, which often shattered and splintered soldiers’ bones. As Samuel Cooper explained in The First Lines of the Practice of Surgery, “The absolute necessity for amputation, however, is yet universally admitted in examples in which the limb is very badly shattered, or crushed, a joint entirely destroyed by caries, the principal blood-vessels injured, and the flesh also badly wounded, or the substance of the limb deeply affected with gangrene, or some species of incurable tumour, attended with serious inconvenience, great pain, and alarming derangement of the health.”1

Below are some eyewitness accounts of Civil War-era amputations.

The bullet severed the capillary artery and shattered the lower end of the femur thighbone. Amputation was found to be necessary, chloroform was administered and Dr. [Harvey] Black performed the amputation. Varicose hemorrhage was so excessive that all the veins were tied, rend[er]ing the operating very protracted and tedious. Findley bore it well and the anesthesia acted fine.2

—John Samuel Apperson

Union surgeon Daniel M. Holt explained the frequent necessity of amputation:

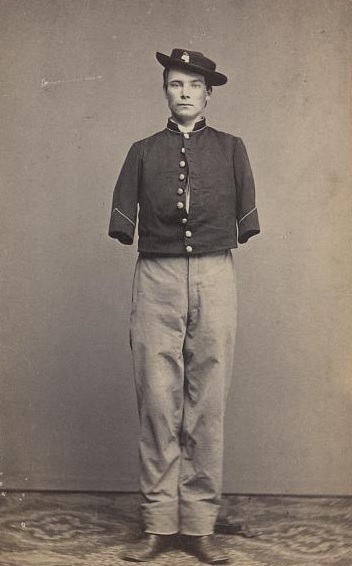

The contents of the gun passed through his hand causing amputation. This was done above the wrist. It comes hard upon him as he is a poor man with a wife and two children; and the wound appears to have been through sheer carelessness. Several such have taken place in our regiment already. We are scarcely called upon to go out on picket without someone coming in hurt more or less by carelessly handling their pieces.3

Throughout the war, there were frequent false claims that surgeons performed amputations without the use of anesthetics. Dr. Jonathan Letterman fought back against this notion with this post-Antietam battle report.

The surgery of these battle-fields has been pronounced butchery. Gross misrepresentations of the conduct of medical officers have been made and scattered broadcast over the country, causing deep and heart-rending anxiety to those who had friends or relatives in the army, who might at any moment require the services of a surgeon. It is not to be supposed that there were no incompetent surgeons in the army. It is certainly true that there were; but these sweeping denunciations against a class of men who will favorably compare with the military surgeons of any country, because of the incompetency and short-comings of a few, are wrong, and do injustice to a body of men who have labored faithfully and well. It is easy to magnify and existing evil until it is beyond the bounds of truth. It is equal easy to pass by the good that has been done on the other side. Some medical officers lost their lives in their devotion to duty in the battle of Antietam, and others sickened from excessive labor which they conscientiously and skillfully performed. If any objection could be urged against the surgery of those fields, it would be the efforts on the part of surgeons to practice “conservative surgery” to too great an extent. 4

Notes:

3. Daniel M. Holt, A Surgeon’s Civil War edited by James M. Greiner, Janet L. Coryell, and James R. Smither (Kent: Kent State University Press, 1994), 36-37.

4. Dr. Jonathan Letterman’s report on the battle of Antietam, Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, I: 19: 113.

Image Credit: Library of Congress.