My plans are perfect, and when I start to carry them out, may God have mercy on General Lee, for I will have none.” So said Major General Joseph Hooker in mid-April 1863 to a group of Union officers about his strategy for defeating Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia. Hooker, who had assumed command of the Army of the Potomac in late January, had spent the previous months reorganizing his own force and gathering intelligence on the enemy, and was now supremely confident that his planned offensive—to attack both flanks of Lee’s army simultaneously—would succeed. Lee, however, seized the initiative, splitting his smaller army not once, but twice, sending Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s corps on a devastating attack against Hooker’s right flank on May 2, then following up this success with further assaults against the Union position at Chancellorsville. By May 7, Lee and the Confederates had scored a clear (though costly) victory against Hooker’s army, prompting President Abraham Lincoln reportedly to remark, “My God! My God! What will the country say?” Below we highlight renditions of the decisive battle, which had produced an estimated 30,000 Union and Confederate casualties.

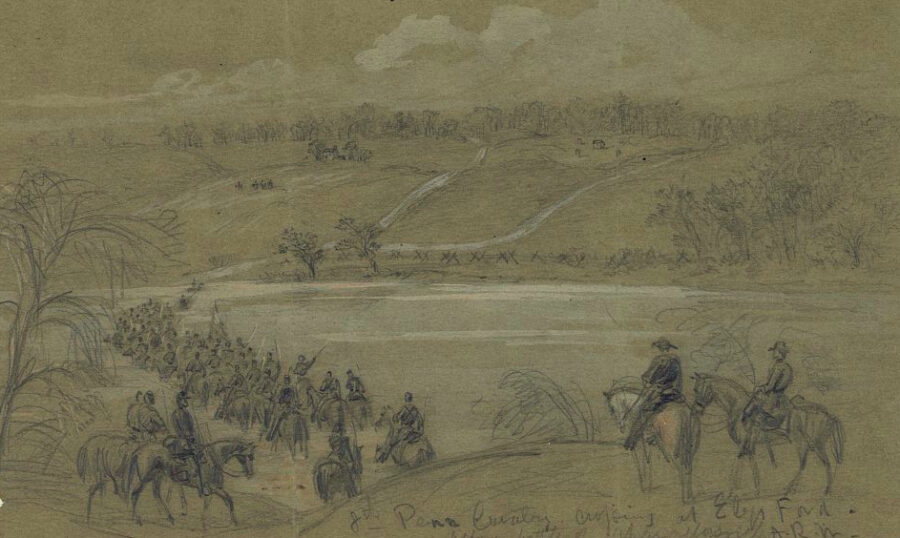

Troopers of the 8th Pennsylvania Cavalry cross the Rapidan River at Ely’s Ford on their way toward Chancellorsville a few days before the battle. (Library of Congress)

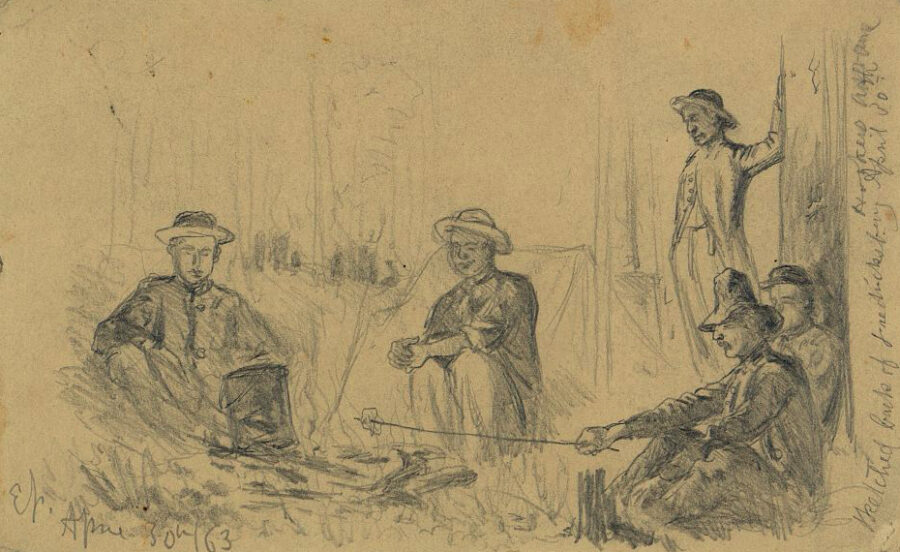

Union troops rest around a campfire in the woods at Chancellorsville on the night of April 30, 1863. The following day, Hooker would continue the advance toward Lee’s army. (Library of Congress)

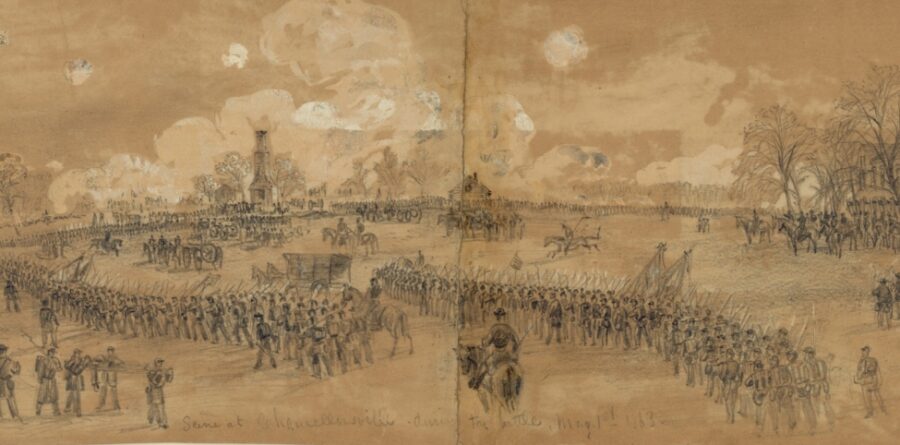

Alfred R. Waud’s sketch of the clash of Union and Confederate armies on May 1. By day’s end, Hooker had halted his brief offensive and called for the army to take up a defensive position around Chancellorsville in hopes that he might force Lee to attack his larger force. (Library of Congress)

Generals Lee and Jackson confer on the night of May 1 in this painting of their “last meeting.” While most of Hooker’s army was heavily fortified in strong positions, the Union right was “in the air” and vulnerable to attack. The following day, Jackson would launch his assault against the exposed enemy flank. (Anne SK Brown Military Collection)

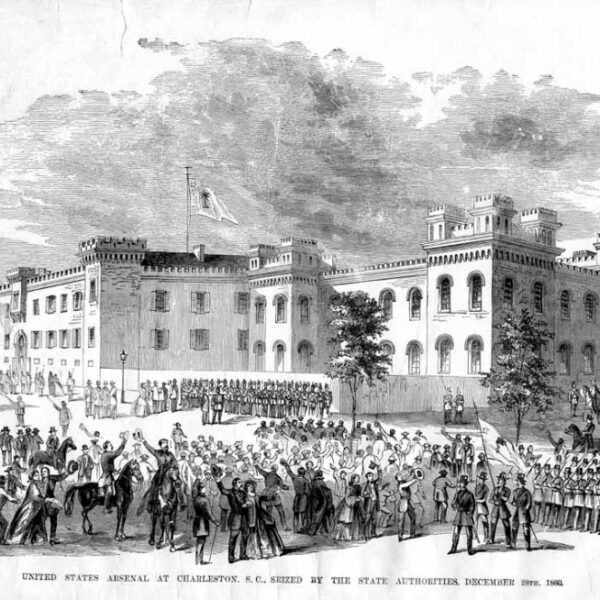

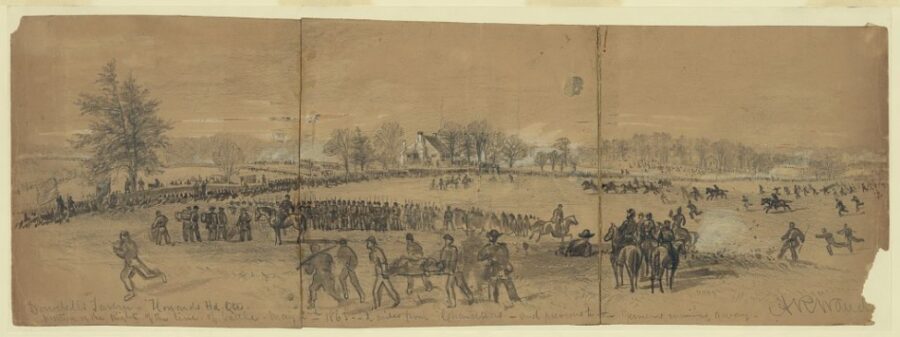

The scene at Dowdall’s Tavern, where XI Corps commander Oliver Otis Howard established his headquarters, during the early morning hours of May 2. Howard and his men would be driven from the area by Stonewall Jackson’s flank attack later that day. (Library of Congress)

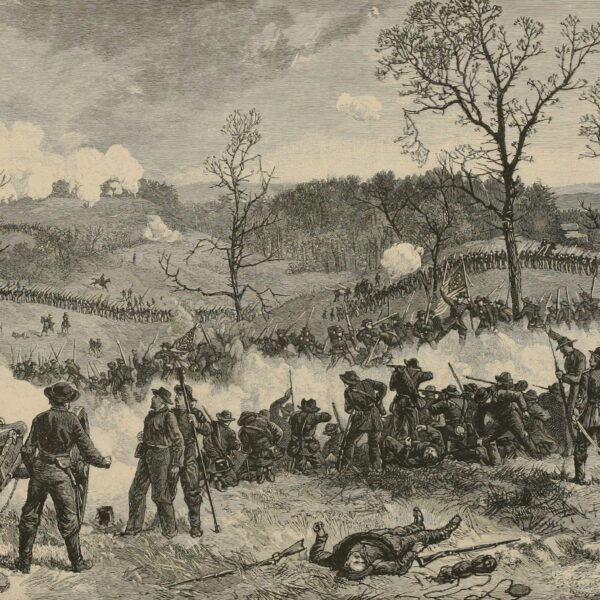

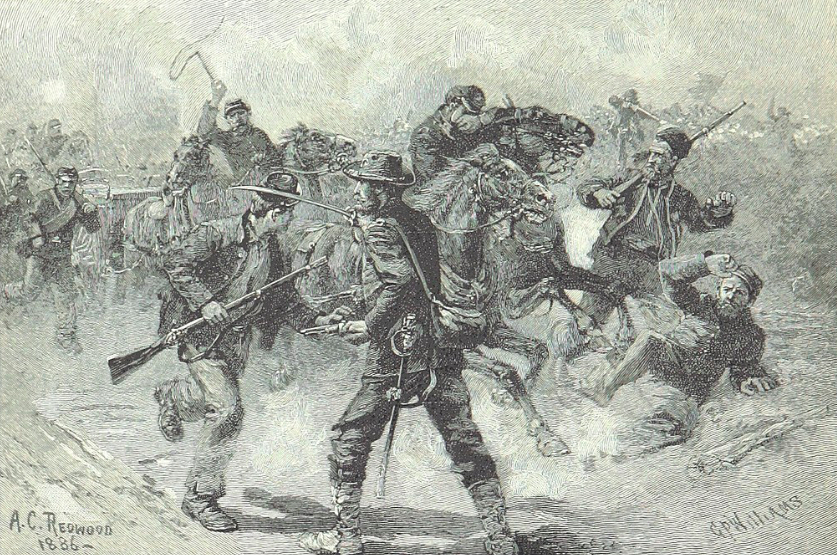

Jackson’s 12,000-man-strong corps started that morning on a 12-mile march to get into position for the attack on the Union right flank, which was anchored by the XI Corps; shortly after 5:30 p.m., the Rebels surged toward the men of the XI Corps, who had been taken largely by surprise—many were at rest or eating dinner at the time—and quickly broke for the rear. (Battles and Leaders of the Civil War)

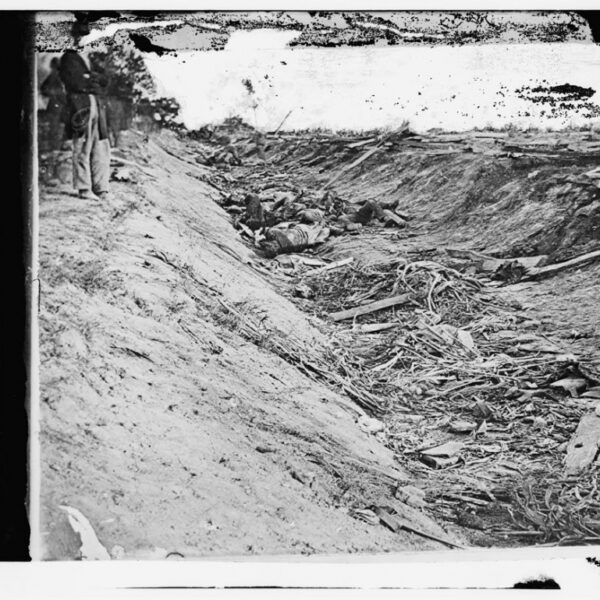

Soldiers from the Union army’s II Corps form a line of battle to cover the retreat of the XI Corps. Jackson’s men had advanced over a mile by nightfall, which brought an end to the attack. That night, while reconnoitering in front of his lines, Jackson was accidentally shot by his own troops, forcing him to relinquish command of his corps for the remainder of the battle. (Library of Congress)

The fighting resumed on the morning of May 3, which saw Confederate forces renew the attack against the Union defensive position at Chancellorsville. (Shown here are Union soldiers in the middle of the Union line defending against advancing Confederates.) By late morning, Hooker’s men began to pull back toward the United States Ford on the Rappahannock River. On the night of May 5–6, Hooker crossed back over the river, ending the Battle of Chancellorsville. (Library of Congress)

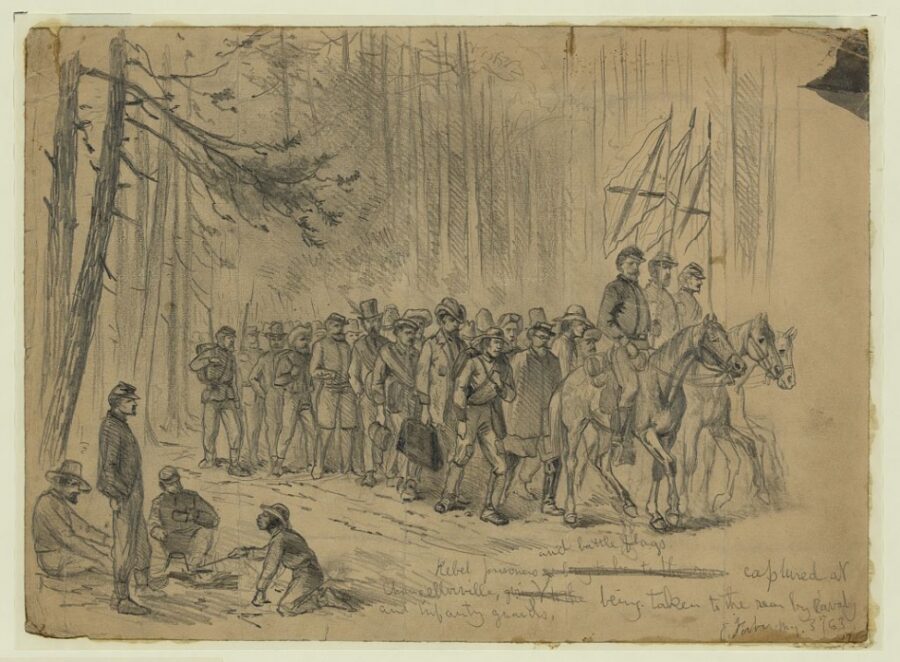

Union soldiers march Confederate prisoners, and captured battle flags, toward the rear on May 3. While the battle was a decisive Confederate victory, some 2,000 of Lee’s men were captured during the engagement. (Library of Congress)

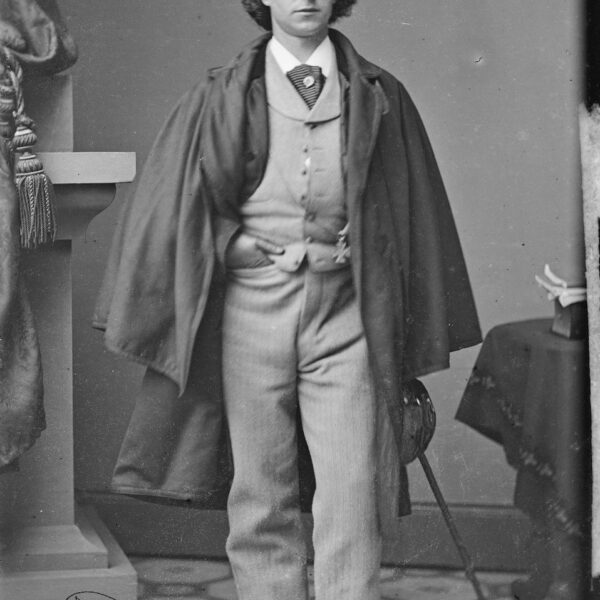

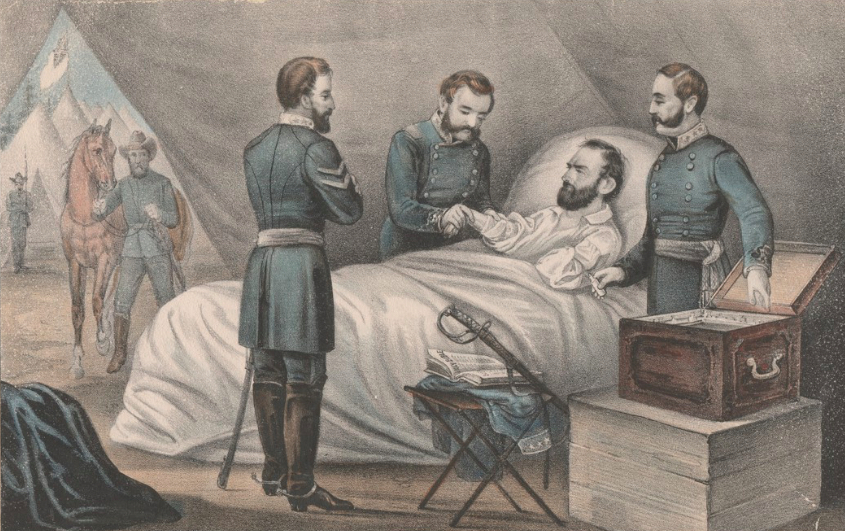

Stonewall Jackson’s wounds had required that his left arm be amputated. He’d never fully recover. Soon after, he contracted pneumonia. Jackson, depicted on his deathbed in this postwar lithograph, passed away on May 10. While Chancellorsville ranked among the biggest Confederate battlefield victories of the entire war, it also robbed the Confederacy of one of its best generals. (Anne SK Brown Military Collection)