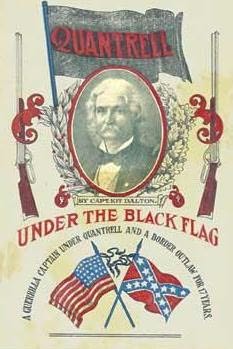

In spring 1880, more than a decade after his famous—or perhaps infamous, locale depending—“March to the Sea,” Union General William Tecumseh Sherman observed of a large gathering in Columbus, Ohio, that “[t]here is many a boy here today who looks on war as all glory.” “[B]ut, boys,” he informed them, “it is all hell.” In his 1914 memoir, entitled Under the Black Flag, ex-Confederate Captain Kit Dalton agreed wholeheartedly with his former foe. “Sherman’s definition of war is true from whatever angle it may be viewed,” Dalton assessed, before quipping that “no individual [Sherman] in the history of civilized warfare did more to make it so.” After all, Dalton confessed to his readers, “the purpose of war is to kill” and men who enlist “do so with the avowed purpose to kill men who have never done them an injury.” “Their destruction,” Dalton alleged, was “only limited by possibilities.”1

Kit Dalton was born in Logan County, Kentucky, in 1843. After initially serving in the Confederate cavalry under Nathan Bedford Forrest, Dalton formed a band of about 30-40 guerrillas that he fondly called his “little army of irregulars.” Partway through his career as a guerrilla captain, Dalton’s command was (willingly) absorbed by William Clarke Quantrill—likely the best-known of Missouri’s irregular chieftains. Under Quantrill’s wing, Dalton participated in major raids against Independence, Missouri, on August 11, 1862, and Lawrence, Kansas, on August 21, 1863. Given his wartime resume as both a regular Confederate soldier as a pro-Confederate guerrilla, it may seem odd that Dalton would agree openly in print with Sherman about anything. But Dalton was not without an ulterior motive: he was only willing to go along with Sherman’s definition of war so far as it might enhance the esteem in which the activities of Civil War guerrillas—that is, Dalton and his irregular associates—were held by southerners in the 20th century.

Warfare as Dalton understood it was a relatively simple affair. “In the nomenclature of all tongues and nations,” he wrote, “war is classified and denominated by the methods used in its practice.” From civilized to barbarous and from regular to irregular, all types of warfare, antiquated and modern, boiled down to a few gruesome realities: “death, devastation, pillage and plunder.” With this in mind, the relative differences between a regular soldier and a guerrilla, as Dalton saw them, all depended on perspective. He employed an anecdote from the Indian Wars to illustrate the point. “When the United States, smarting under the insubordination of some petty chief, plants a battery on a tumultuous reservation and sends a hardware store hurling through the tented village, our maroon brother is appalled at the barbarity of civilized warfare,” offered Dalton. But, “when that same battery is bushwhacked by the noble red man and a few curly locks of somebody’s darling hung to the girdle of the victor,” he countered, “civilization turns its pious eyes upward and loudly petitions heaven for vengeance, swift and terrible.” In other words, according to Kit Dalton, the activities of himself or Quantrill along the border were only different from Sherman’s in Georgia or the Carolinas because “civilization” said so.2

Consequently, Dalton did not think much of civilized soldiers or their rules of war. “Civilized warfare,” he wrote to that end, “is that method practiced by armies whose soldiers too often fight for pay in complete ignorance of the causus belli, and who look to the parent government for food and raiment and medical care while engaged in the struggle, and wholesome pension when the strife is ended.” On the other hand, “guerilla [sic] warfare is that method practiced by men who are in an ugly humor with the enemy and want to kill instead of capture, and who look to their own prowess for what pay they may receive for their services.” This more honorable breed of men, Dalton insisted, “have never heard of a pension roll” and “have no desire to receive an easy berth at the hands of the suvren voter when the struggle is ended.” The irregular or bushwhacker as Dalton envisioned him was a “free lance” with a good cause—a man who fought “because he wants to hurt somebody and makes the enemy support him while he is engaged in their destruction.”3

Despite his less-than-kind explication on Union regulars and their commanders, Dalton knew how to play the memory game; therein, he was seemingly less interested in elevating guerrillas above their regular counterparts (something that even the most hopeful of ex-guerrillas knew was simply not a possibility in 1914 given the parameters of the Lost Cause) than in establishing an equal position beside those regulars on the landscape of Civil War memory. And in the big picture, this really wasn’t so bad. As the 20th century marched on the United States involved itself in new wars. In the meantime, Dalton and his men weren’t getting any younger. In fact, their numbers were thinning rapidly. As the ranks of ex-guerrillas dwindled, it became clear that the only fate worse than having to reconcile with former enemies for the sake of being remembered was to be written out of the story completely. This sort of damnatio memoriae was simply not acceptable to men like Dalton, who, himself, died just six years after the publication of his memoir.

Dalton concluded that he had “served as a regular and as a guerilla,” and that he had “served against ‘regulars’ and against every form of Yankee guerilla—from the gallant scout to the Kansas Red Leg.” So what was Dalton’s expert opinion on the matter? “In all fairness, after many years of service and strife,” he testified, “the guerilla methods are no more reprehensible than that of a regular army.” After all, “leaden death from a high power rifle in the hands of a regular is just about as permanent as death from a blunderbuss in the hands of a jayhawker.” And perhaps more relevant to survivors of the Civil War, he asserted that “a sleeve made empty by a ‘regular’ is just about as awkward an arrangement as one made vacant by a guerilla.”4

Since Under the Black Flag was published in 1914, the vast majorities of Civil War historians and buffs have discounted Dalton’s attempt to legitimate guerrilla warfare and to pull it within the folds of mainstream Civil War memory. Even academics who buy into the notion of “total war” typically cannot bring themselves to accept Dalton’s cynical explanation of the differences—or lack thereof—between “civilized warfare” and “guerrilla warfare.” Whether these parties are right or wrong to disagree with Dalton (consensus doesn’t seem likely), he did find one unlikely ally in the form of an ex-soldier and fellow cynic. Infantryman-turned-author Ambrose Bierce, who saw action at Shiloh (1862) and Kennesaw Mountain (1864), may have best encapsulated Dalton’s understanding of killing and war with a single definition provided in his satirical masterpiece, The Devil’s Dictionary:

Homicide, n. The slaying of one human being by another. There are four kinds of homicide: felonious, excusable, justifiable, and praiseworthy, but it makes no great difference to the person slain whether he fell by one kind or another—the classification is for advantage of the lawyers.5

Matthew C. Hulbert is a doctoral candidate in History at the University of Georgia.

1Kit Dalton, Under the Black Flag (Memphis, TN: Lockard Pub. Co., 1914), 16.

2Ibid.

3Dalton, Under the Black Flag, 16-17.

4Dalton, Under the Black Flag, 17.

5Ambrose Bierce [edited by David E. Schultz and S. T. Joshi], The Unabridged Devil’s Dictionary (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2002), 111.