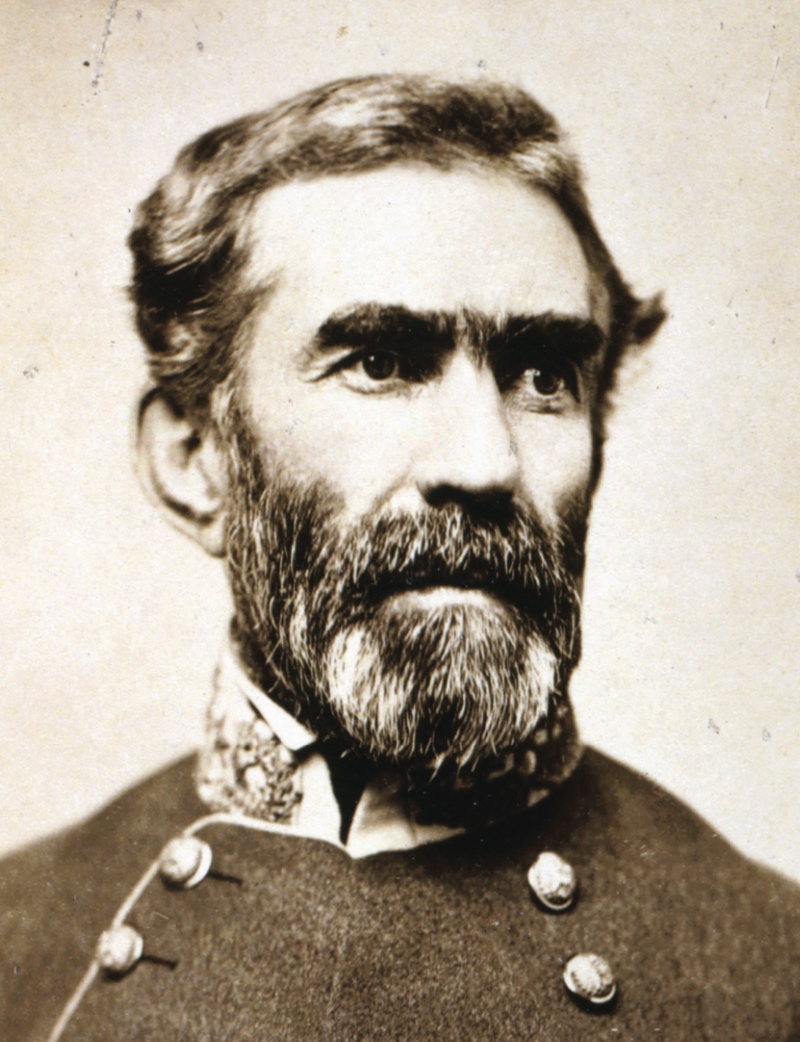

General Braxton Bragg

The art of command remains an elusive and complex concept for historians of the Civil War, and debates about command decisions and methods hold a distinctive place in its history. The human element is among the most complicated factors—no surprise to anyone who has been part of an organization or group. Armies are, after all, made up of and directed by humans, all of whose weaknesses and shortcomings can hinder the best-laid plan’s success. In addition, leading Civil War forces at the tactical or operational level was frequently an exercise that required commanders to first see a problem in order to develop and implement a solution. When at the crossroads of decision, a general’s success or failure sometimes turned on his skill at identifying problems and adapting their solutions to the human beings under his charge.

A leader’s range of influence shaped his capacity to manage his subordinates and dictate their behavior through his instructions. This structure relied on the nature of a commander’s relationships with his subordinates, his ability to provide directives with clarity, accuracy, and appropriateness, and his army’s capacity or willingness to follow orders as circumstances decreed. Personality played an essential role in how commanders and subordinates interacted, interactions that were key to an army’s success. Personality clashes were a common cause of leadership dysfunction. Many conflicts arose from substantive disagreements, command blunders, misjudgments, adversary acumen, and plain poor luck, as well as poisonous personal dynamics between generals who simply did not like one another and, even sharing a cause, could not put their animus aside.[1]

With these myriad considerations in mind, few episodes of command confusion and ragged interpersonal dynamics can rival the experience of General Braxton Bragg and the Confederate Army of Tennessee in September 1863, in the mountains of northwestern Georgia. The engagement at McLemore’s Cove, also known as the Battle of Davis’ Crossroads or the Battle of Dug Gap, took place on September 9–11, as part of the Chickamauga Campaign, the Union army’s attempt to capture Chattanooga, Tennessee. It provides both a fascinating window into the command challenges and strained relationships between Bragg and his subordinates that summer, and an object lesson in the difficulty of managing and directing field forces in the Civil War. Historians, military experts, and participants have all offered explanations for the Confederates’ failure, including Bragg’s ineptness, the poisonous command culture inside the Army of Tennessee’s senior officer corps, and even cowardice. When taken together, these various interpretations still account for only a portion of what occurred. Unfairly, perhaps, Bragg has been the butt of innumerable jokes among buffs and on the Civil War Round Table circuit; students of the Confederacy’s western campaigns know well Bragg’s difficulties with his own high command.

In early 1863, from their winter quarters in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, and on the heels of a hard-won victory at Stones River, Major General William S. Rosecrans and his Army of the Cumberland arranged for a war of maneuver. With four infantry corps, along with a corps of cavalry, Rosecrans developed a bold operational and tactical plan. Tempering his confidence was his own testy civil-military relationship with the U.S. War Department, who repeatedly urged him to launch his campaign before he thought it prudent. While Rosecrans’ initial reticence caused much consternation in the Union leadership in Washington, D.C., his efforts that summer of 1863 would deliver the Lincoln administration the near-complete recovery of Middle Tennessee from enemy control—though without destroying the enemy forces. Opposing the Army of the Cumberland was Bragg’s Army of Tennessee, consisting of four infantry corps and a reserve corps, along with two cavalry corps.[2]

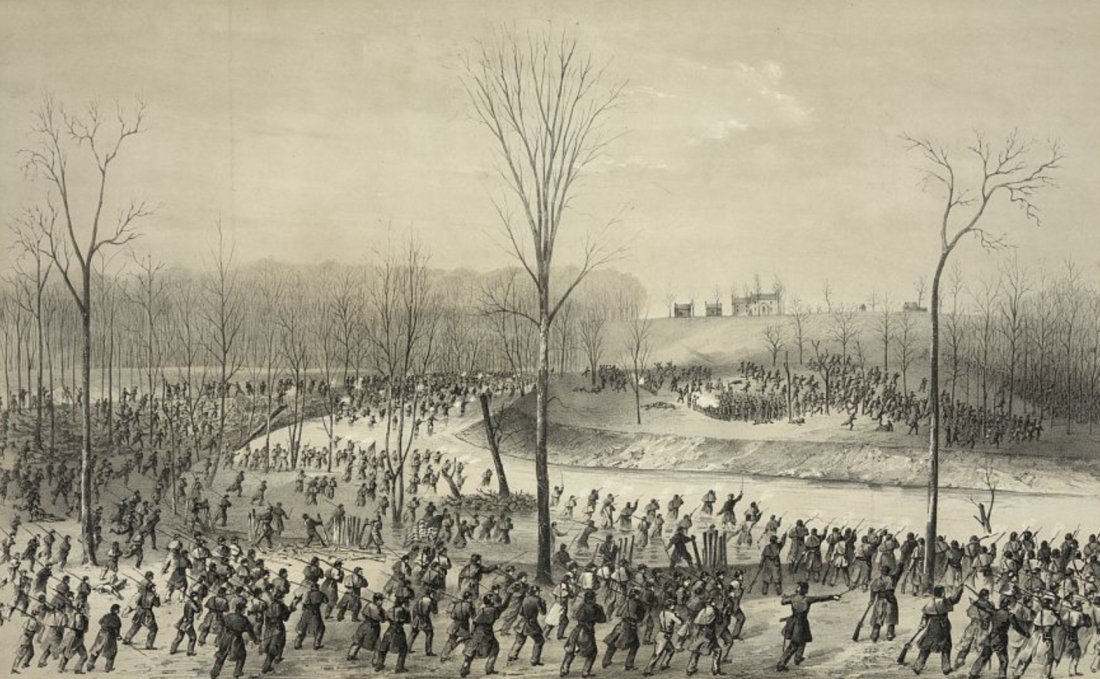

The Battle of Stones River

In planning his strategy, Rosecrans faced a challenging topographical environment of trackless mountain ridges with few resources or opportunities for resupply. The Union army aimed to isolate and secure Chattanooga, an important staging point for future efforts to penetrate the Confederate heartland of Alabama, Georgia, and beyond. Rosecrans’ strategy was audacious; it depended upon both deception and maneuver and required the dispersed elements of his army to move with speed and flexibility in a fluid operational environment amid difficult terrain and with tenuous supply. On August 16, with Bragg’s attention fixed north of Chattanooga, Rosecrans began his offensive. He was convinced he had the measure of his enemy, and intended to maintain the initiative by continuing the war of maneuver that had thus far served him so well. With the Confederates pinned to Chattanooga and its environs, Rosecrans knew he could strike Bragg at the time and place of his choosing. So confident was Rosecrans of imminent victory that he chose to ignore the advice of his best corps commander, George H. Thomas, and split his army into three large columns of corps for the tricky march through the mountain gaps shielding Chattanooga. If his plan succeeded, it would force the Army of Tennessee either to evacuate Chattanooga and fall back on its communications with Atlanta, or to remain in the city, isolated and out of supply.

•••

On September 6–7, word came to Bragg of the Union turning movement into Alabama and Georgia. He made a dramatic choice and ordered the Army of Tennessee to evacuate Chattanooga. It turns out, this was a very good decision. Bragg recognized that Rosecrans’ plan was rooted in overconfidence, and he saw the potential to turn around what had been a long summer of bad fortune. He thought that Rosecrans placing his various columns among the jagged mountains and out of easy supporting distance of one another may have been a serious mistake. Bragg hoped to locate and attack one of the isolated Federal corps, break it up, and then place the bulk of his army between Rosecrans’ remaining forces. This would not only disrupt the Federals’ turning movement and recover Chattanooga for the Confederacy, but also place Bragg’s army in a favorable position to defeat Rosecrans’ dispersed columns in detail.

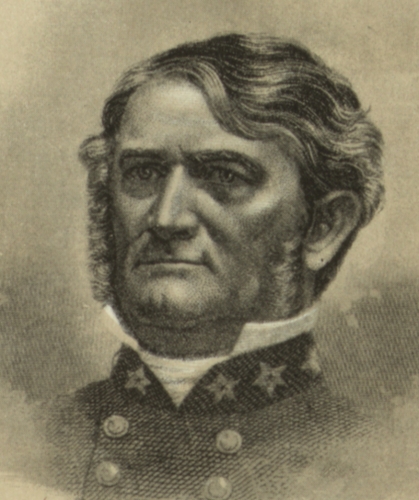

There was, however, that ubiquitous and troublesome problem: the human factor. Bragg suffered from a dysfunctional command relationship among his chief subordinates. A vocal bloc of anti-Bragg generals—led by the wily Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk (a politically connected favorite of President Jefferson Davis) and including such officers as Lieutenant General Daniel Harvey Hill, Major General Simon Bolivar Buckner, and others—waged a bitter campaign against their commander, co-opting peers and undermining him at every turn. Bragg was either oblivious to their open hostility or, more likely, unwilling to confront their insolence, and so did little to counter his critics or impose his authority over their machinations. Anything Bragg hoped to accomplish depended on getting his generals to go along, which, in the summer of 1863, was easier said than done.[3]

Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk

Sensing the opportunity against Rosecrans that he had hoped for, Bragg ordered Major General Thomas C. Hindman to take his division into the cove on a 13-mile night march, and to assault Major General James S. Negley’s Union division, which was supported by Brigadier General Absalom Baird’s division, in the flank at Davis’ Cross Roads. Hindman’s division was part of Polk’s corps and the nearest available unit for the operation. Though new to the army, Hindman had a hard-fighting reputation and Bragg much preferred him to the insubordinate Polk or the unreliable Major General Benjamin F. Cheatham, whose division was also close at hand. Unfortunately, Bragg misread his new division commander’s sensibilities. Hindman was already on the wrong foot with his troops, almost from the start imposing harsh discipline and alienating his officers and enlisted men alike. Worse, despite his reputation for boldness, Hindman actually had a tendency toward excessive caution when under duress, and may also have been warned by Polk and others about Bragg’s tendency to blame his subordinates when operations went awry.[4]

Bragg knew how important this mission was and, for insurance, instructed corps commander Hill, also new to the army, to support Hindman in the cove. Hill had a deserved reputation for irascibility and a stubborn streak that won him few friends; Lee had transferred him out of Virginia and into Bragg’s army, where he took over William J. Hardee’s old corps. President Davis approved the transfer without consulting Bragg, who clashed with Hill practically from the start. It took no time at all for Hill to take on the Army of Tennessee’s habit of questioning Bragg’s every move and by September he had fallen in with the anti-Bragg clique.

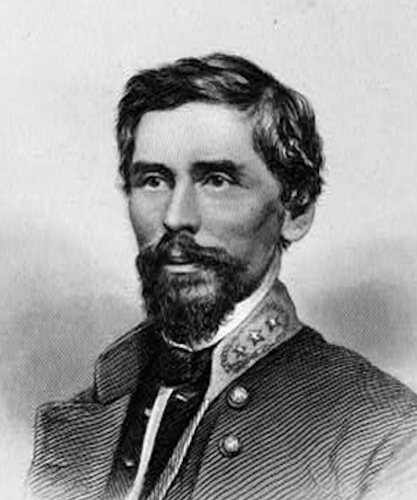

Then there were Bragg’s orders—flawed from the start. He lacked concrete information on the enemy’s whereabouts, and in his conference with Hindman, he made an offhand mention of possible enemy forces on what would be Hindman’s right flank. This apparently stuck in the division commander’s mind, becoming a preoccupation that would dramatically affect his subsequent performance. On September 9 Hill’s headquarters were at LaFayette, about 14 miles from Bragg’s headquarters at Lee and Gordon’s Mills. Hill’s greatest asset at that time was that the army’s most dependable division, that of Major General Patrick R. Cleburne, was part of his corps. But Hill had posted Cleburne’s troops along Pigeon Mountain, some distance from Negley’s and Baird’s positions. So Hill and Hindman would have to do for the strategy to succeed, with Cleburne serving as insurance.[5]

Major General Patrick R. Cleburne

Bragg had unwittingly created a complicated and uncertain command arrangement, partially to cut out reliance on even more difficult subordinates like Polk and Cheatham. He assigned Hindman, a division commander, to take charge of what was an under- strength corps composed of units from three separate existing commands. Moreover, Bragg apparently expected Hindman to answer directly to him while also consulting with Hill in LaFayette and coordinating with Cleburne’s borrowed division. Bragg later inserted Buckner, another corps commander, into this leadership equation while leaving Hindman in nominal charge of the operation. Bragg defined none of these command relationships explicitly, nor did he explain his reasoning for this odd arrangement; rather, he seems to have expected his subordinates to work out the details themselves as the situation unfolded. Further, Bragg granted Hill broad discretion to act—or not—as the Carolinian saw fit through the early stages of the operation. But he didn’t tell either man what he expected them to do to achieve his desired goal. So Hindman, given this much latitude and uncertainty, marched part of the way to his objective and then sat idle.[6]

By the time the Confederates had ironed out their command problems, Negley’s and Baird’s divisions were already withdrawing from McLemore’s Cove, leaving Bragg, Hill, Hindman, Buckner, and the rest of the bewildered Army of Tennessee leaders to bicker among themselves about yet another squandered opportunity. That evening Bragg rode down and joined Hindman and the others at Davis’ Cross Roads. By most accounts the meeting was highly unpleasant, with Bragg demanding to know where the enemy had gone and receiving no good explanation from Hindman.[7]

The truth of the matter is that the failure at McLemore’s Cove resulted from Bragg’s inability to manage people, to command his subordinates—whether they liked him or not—to carry out his orders. Moreover, the unreliable and haphazard command-and-control methods customary to Civil War armies served as subtext to these failures, amplifying any existing problems within the Army of Tennessee’s leadership. Bragg’s command failure in September 1863 revealed his greatest leadership weakness: an inability or unwillingness to account for the human element in his evolving and often dysfunctional relationships with his subordinates.